SUMMER 2023

In a 1952 television interview, American poet Robert Frost said he preferred to spend time with people who have “a definite personality.” The best trait in people, he suggested, “is taut boldness.”

Then Frost added: “People will tell you that freedom lies in being cautious.” He shook his head. “Freedom lies in being bold.”

Freedom lies in being bold. It’s hard to come up with a better encapsulation of Pacific Legal Foundation than that.

PLF has advanced freedom for 50 years because at the heart of every PLF case are bold people with “definite” personalities, to borrow from Frost. (Incidentally Frost, like PLF, was born in California.)

Bold history is made by bold people. Protecting freedom takes expertise, of course, and teamwork; but it also demands a certain kind of individual spirit. An adventurousness, a daring. That’s what PLF clients and attorneys bring to their work—a bold attitude and a willingness to take risks.

Not all cases end in victories, of course. The cases wouldn’t be risks if they did. But it’s through tough cases—the longshots that other firms aren’t interested in, the unpopular stances that won’t win media praise—that freedom is protected.

When PLF was founded in 1973, I hadn’t yet started my legal career. In 1973, I was a young astrophysicist studying high-energy particle astrophysics. Essentially, my colleagues and I were trying to understand the far reaches of the universe.

What PLF’s first attorneys were doing at the same time was its own form of discovery: They were seeking to understand whether a small group of dedicated people could advance liberty through the law, even when significantly outmatched in size and budget by government opponents.

Fifty years later, the universe is still largely a mystery. But PLF has found its answer.

As of this writing, Pacific Legal Foundation has overturned countless unconstitutional laws, represented thousands of Americans, and won 17 Supreme Court victories. (Remarkably, three of those victories came this year, with two huge wins—Sackett v. EPA and Tyler v. Hennepin County—announced by the Court on the same day.)

I was proud to become chair of PLF’s Board of Trustees in 2021. The far reaches of PLF’s impact are still being discovered, and advancing liberty with this team is an adventure for the bold.

Brian G. Cartwright

Chair, Board of Trustees

Los Angeles, CA

A note: You usually hear from Pacific Legal Foundation President and CEO Steven D. Anderson on this page. For this issue, Steven wrote the opening article, so we asked Brian G. Cartwright, chair of PLF’s Board of Trustees, to pen the opening letter.

Choosing To Be Bold

Steven Anderson

president and ceo

ON A YELLOW COUCH in North Carolina. That’s exactly where I was seven years ago when my life changed forever. I was visiting my in-laws for our oldest child’s spring break, and I was doing what every parent does when their kids are napping—I checked my work emails. One was an unsolicited message from a recruiter asking—in true headhunter-speak—if I knew anyone that might be interested in leading a long-established public interest law firm. I was already at a long-established public interest law firm, the Institute for Justice, and had I not been at spring break, I’d have deleted the email straight away. I wasn’t looking for a job and was quite content where I was.

But I happened to mention it to my wife, Lyndsay, who was sitting next to me, chuckling that I’d received another one of those emails, which I routinely sent to the trash. Her response was a surprise—what would it hurt to explore the possibility? So we did explore, and in 2016, I left my job as executive vice president of IJ, packed up our rowhouse on Capitol Hill, and moved along with Lyndsay and our sons, Thomas and Henry, to another capital, Sacramento, to become president of Pacific Legal Foundation. It’s strange to me to think that my entire life’s story has been written in part because I had sleepy kids and an impulse to clean out my inbox. Sometimes the seemingly inconsequential moments have the most profound impact.

I was attracted to PLF, then a 43-year-old law firm, because it had untapped potential—and there’s something exciting about joining an organization that’s still working to determine its mission and identity. You’re putting yourself in a moment where paths diverge, when the choices you make—like the one I made sitting on that couch—will have a reverberating effect. And not only on the organization, but also our nation.

It’s strange to me to think that my entire life’s story has been written in part because I had sleepy kids and an impulse to clean out my inbox.

Since its founding in 1973, PLF has always had a history of success. The organization has always drawn talented, passionate people to the cause of liberty—people who made choices in their own life paths that bring them to jobs at PLF.

But in its old-school days, as PLF advanced liberty, it also spoke with a soft voice. For years we had no dedicated communications department. Sometimes there’s value in quietly getting your work done without caring what the outside world says about you. But the stories we tell about ourselves are also important. After all, if you’re winning Supreme Court cases and no one’s paying attention, how much does it matter?

There’s value in opening your doors and letting people know who you are as an organization. There’s value in letting a larger community be part of what you’re trying to achieve.

That was the impetus behind this year’s 50th Anniversary Gala. The purpose wasn’t to throw a party—although we hope our 600 guests had fun, and I certainly did—but to throw open our archives and show our larger family of supporters and allies who we are.

We held the gala in the National Portrait Gallery in downtown Washington, DC. The museum was established by an act of Congress in 1962 to display portraits of “men and women who have made significant contributions to the history, development, and culture of the people of the United States.” It’s a place I often visit, and it was a fitting place for us to gather, surrounded by the faces of people who helped build America.

We sue the government when it violates Americans’ rights. We take risks. We stand alongside clients who’ve been forgotten by others. And we openly claim our identity as unapologetic freedom-fighters.

As I stood on stage in the museum’s magnificent atrium, looking out at the seated guests, I recognized only a fraction of the faces. But everyone in that room had a connection to PLF. Some had donated money so that PLF can represent our clients for free; some were attorneys at other firms who’d supported PLF cases; and some were clients who’d been in the trenches with PLF attorneys.

In my opening remarks, I reminded the room that PLF started in 1973 with just three staffers in a borrowed office in Sacramento. Fifty years later, with more than 100 staffers working across the country, our firm is a national force.

This term we litigated three of the roughly 60 cases the Supreme Court heard. And—as I hope you’ve heard by now—the best part is we won all three. That might be unprecedented in the history of public interest law.

In Wilkins v. United States, the Court leveled the playing field for property owners suing the government. Our client, blacksmith Wil Wilkins, sent us a touching handwritten letter he received from a high school student after the decision. “I am overjoyed that there are still people fighting for our individual rights as citizens!” the student wrote.

Just before this magazine went to print, mere minutes apart, the Supreme Court announced two more victories for PLF, both unanimous.

In Tyler v. Hennepin County, the Court ruled that home equity theft is unconstitutional. The government cannot take more than it is owed when settling tax debt. Mother Jones—which doesn’t often praise PLF’s property rights work—called it “a true unicorn of a case” because the decision “made just about everyone happy for once.”

And in Sackett v. EPA, a case PLF has been litigating since 2008, the Court put significant limits on Clean Water Act enforcement, establishing that the EPA and Army Corps of Engineers cannot exert regulatory control over semi-soggy parcels of land like the Sacketts’. It’s already being hailed as a landmark case. The Wall Street Journal editorial board correctly called the Sacketts’ victory “a triumph for the liberty of every American.”

At 50 years old, fresh off the biggest year in PLF history, our organization is ever more confident in who we are. We sue the government when it violates Americans’ rights. We take risks. We stand alongside clients who’ve been forgotten by others. And we openly claim our identity as unapologetic freedom-fighters.

Here’s to PLF celebrating 50 years of being bold. ♦

An Immigrant Goes Up Against a Power-Hungry New Agency

Jeremy Talcott

attorney

MEN AND WOMEN who grew up under the world’s cruelest governments are different from the rest of us.

Americans are lucky. Even those of us who regularly sue the U.S. government will admit how lucky we are: In America, we can hold up our Founding documents—even shake them in the government’s face— and say, “Here it says I was born with the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. The government exists to secure my rights. It works for me.” Our earliest constitutional amendments are devoted to prohibiting certain government actions. And most of us have never known life without these protections.

The land overlooked the Pacific Ocean. There, she and her husband could build a modest home for themselves—the kind of home Viktoria’s father would have wanted for her, a place where she’d always feel comfortable, safe, and free.

People who’ve experienced totalitarianism are more wary of government. They’ve seen what it is capable of doing.

Viktoria Consiglio was like that. Viktoria grew up in Germany under Hitler’s reign. Her mother was Jewish. Her father was terrified for their family. The Consiglios’ own government was imprisoning, stealing from, and killing people just like them.

In 1956, the family finally managed to leave Germany for America. The United States had “the best Constitution in the world,” Viktoria’s father told her. By the 1970s, Viktoria had a comfortable, middle-class life in California. She worked as a bookkeeper; her husband was a pipefitter. Their decision to settle in California pleased Viktoria’s father: It was a place where people seemed to flourish.

When Viktoria’s father died, he left Viktoria everything—including money for her to set down real roots on the California coast. In November 1976, Viktoria used her inheritance to buy a two-acre plot of land just south of Carmel. The land overlooked the Pacific Ocean. There, she and her husband could build a modest home for themselves—the kind of home Viktoria’s father would have wanted for her, a place where she’d always feel comfortable, safe, and free.

“California: bordering always on the Pacific and sometimes on the ridiculous.”

George Carlin

comedian

1976 WAS THE same year Governor Jerry Brown signed the California Coastal Act. The bill endowed the new California Coastal Commission with extraordinary regulatory power over the state’s 1.5 million acres of coastal land. Nothing could be done on the land without the commission’s express permission

Brown seemed to quickly regret giving the commission so much authority: By 1978, he was openly calling the commissioners “bureaucratic thugs.” The commission “wrapped its tentacles around everything,” The Wall Street Journal later complained. It was “a perfect example of well-meaning liberalism gone terribly awry.”

The commission said it wanted to keep the land free of any structure that would block motorists’ fleeting view of the ocean as they drove down the nearby highway.

Viktoria already had a County-issued building permit to start construction on a 1,000-square-foot home on her land. But she now needed the California Coastal Commission to sign off.

The commission denied Viktoria’s permit request. There was no ecological rationale for the denial, no practical reason why a home couldn’t be built on the land. Instead, the commission said it wanted to keep the land free of any structure that would block motorists’ fleeting view of the ocean as they drove down the nearby highway. The Consiglios’ planned home—for which they’d hoped to do much of the wiring and carpentry themselves—wasn’t sufficiently “subordinate to the character of its setting,” the commission said.

Meanwhile, 18 of the 27 plots surrounding Viktoria’s empty land already had houses sitting on them. One of Viktoria’s neighbors had gotten his building permit approved, but at a cost: He’d agreed to hand over a chunk of his land to the California Coastal Commission.

Viktoria resisted pressure to make the same concession. Her land represented her father’s entire life savings and his dream for her future. She couldn’t stomach giving up part of that land to the government under coercion. That wasn’t what her family had come to America for, or why her father had bequeathed his life savings to her. She’d bought the land, fair and square. Why shouldn’t she be able to build a small home on it?

“We need to change the policy of allowing property owners to think they can do what they want with their land merely because it’s theirs.”

Rockefeller Brothers Fund

in a 1973 report

THE CALIFORNIA COASTAL COMMISSION’S power grab came at a difficult moment for property rights in America.

In an influential 1971 article in The Yale Law Journal, law professor Joseph Sax declared a “need for a reconsideration of the notion of property rights.” The public had rights that extended onto otherwise-private property, Sax argued. He urged courts to recognize the “interconnectedness” of various property uses, which defied lot lines and boundaries. What a homeowner did with his private property was no longer just for him to decide, according to Sax; it was part of a network of overlapping activities that required government oversight—and restriction.

It was an unsettling perspective that elevated amorphous community interests—like, say, a motorist’s interest in seeing the ocean for a few seconds as he zipped along a highway—above the personal right to improve one’s own property. Sax suggested ways the government could use its police power to exert control over private land without having to pay just compensation to property owners.

Building a home is both a sign that you’re actively shaping your own destiny and a marker to all that you’ve laid down your own roots in a free country.

This new way of thinking about property rights aligned nicely with the 1970s push for increased environmental and land use regulation. The government could now advance public causes by controlling the use of private land—sometimes to the point of prohibiting virtually all use by the actual landowners.

Staff at the California Coastal Commission recognized they were bumping up against a foundational American right: the right to acquire and use property. According to Jefferson Decker’s book, The Other Rights Revolution, early memos from commission staffers questioned “the absence of a precise standard” or “firm dividing line” separating legal regulation from an unconstitutional violation of private property rights. The commission knew that it was treading on questionable ground.

For Americans, the ability to build a home on your own land is indelible; it’s part of the stories we tell, what we work toward, and how we measure our independence. “Property is surely a right of mankind as really as liberty,” John Adams wrote in 1787. Since our founding, homeownership has always been a mark of success, especially for immigrants who’ve made their way westward to start a new life. Building a home is both a sign that you’re actively shaping your own destiny and a marker to all that you’ve laid down your own roots in a free country.

“Real estate is an imperishable asset, ever increasing in value. It is the most solid security that human ingenuity has devised. It is the basis of all security and about the only indestructible security.”

Russell Sage

19th-century American financier and politician

WHEN IT BECAME CLEAR to Viktoria that the California Coastal Commission wasn’t going to budge—despite any internal doubt about the constitutionality of its actions, the commission was driving full steam ahead to block housing on land like Viktoria’s—she came to a hard decision. If the commission wanted the land that badly, she’d simply sell the commission her land. That would mean giving up her beautiful coastal plot, but at least the government would probably give her a fair price for it.

Begrudgingly, Viktoria offered to sell her land to the commission for use as a reserve.

The commission refused.

Here was the awful truth about the California Coastal Commission: It wanted to keep the land empty for the public, but it didn’t want to pay for the land. The commission wanted private property owners to bear the full financial burden of the state’s decisions. The approach was all stick, no carrot. The commission had the power of the state behind it. What possible recourse could property owners have?

“Private property, an integral part of the American Dream, is under attack by those determined to abolish private ownership and to replace it with ‘social ownership.’”

Raymond Momboisse

Pacific Legal Foundation attorney, 1980

PACIFIC LEGAL FOUNDATION HAD been around for only five years when, in 1978, Viktoria Consiglio came to the firm with her story. PLF attorneys were eager to help Viktoria sue the commission. It was “just the kind of lawsuit the Pacific Legal Foundation likes, a defense of property rights against government interference,” The Western Law Journal reported.

Begrudgingly, Viktoria offered to sell her land to the commission for use as a reserve.

PLF began pursuing Viktoria’s case on two fronts: the courts and the media.

“My father was so relieved that I was making my home in California that he left me his life savings to buy a lot near the ocean,” Viktoria told Hayward Review in a 1980 interview arranged by PLF. “What happened to the American Dream? What happened to the freedom of little property owners like me? What happened to the Constitution I swore to uphold when I became a citizen?”

Reason Magazine slammed California: “The state has decided it likes the view from the Consiglios’ property—but not enough to buy the property to keep as a wilderness area.”

Even the Los Angeles Times was on Viktoria’s side. “It is hard to imagine any plight worse than that of Viktoria Consiglio, a Seaside bookkeeper, and her husband, a Civil Service pipefitter,” the newspaper declared.

Meanwhile, the commission was playing hardball in court. By 1980, the California Coastal Commission had over 200 employees and an annual budget of $10 million. It could afford to drag on litigation for years. That was how the state chose to spend its money—not by compensating property owners, but by beating down anyone who pushed back against its bullying.

The Result of the Case…

BY 1982, VIKTORIA HAD HAD ENOUGH.

Her property, which she’d bought six years earlier, was just sitting empty. She and her husband weren’t wealthy. They’d been paying property taxes on land the state wouldn’t let them use. They needed to move on.

Viktoria and her husband decided to give up and sell their land for whatever they could get. It was a disappointing end to their fight.

But elsewhere in California, another homeowner had been reading about the Consiglios’ lawsuit.

Patrick Nollan had already signed an agreement to give up a third of his oceanfront property in exchange for a California Coastal Commission permit when he read about the Consiglios’ lawsuit and learned about Pacific Legal Foundation.

In 1982, the same year the Consiglios were forced to give up their land, Pat Nollan spoke to PLF attorneys on the phone. Then he went to the county office, asked to see the permit agreement he’d signed, and quickly tore it up. PLF was going to take up Pat’s fight.

In 1987, Pat and PLF won their case against the California Coastal Commission at the United States Supreme Court. What started with Viktoria in 1978 was finally finished by Pat a decade later—and Viktoria’s faith in the U.S. Constitution is vindicated by cases PLF continues to win to this day. ♦

The Man Who Got Bald Eagles Taken Off the Endangered Species List

Damien Schiff

Senior Attorney

Joseph Kast

Creative Manager

GOVERNMENTS CAN BEHAVE in extreme ways when it comes to sacred animals. In Ancient Egypt, anyone who caused the death of a cat, even accidentally, was put to death. In India today, 20 of 28 states prohibit the killing or sale of cows, which in Hinduism are considered a sacred symbol of life. (The laws were upheld in 2005 by the Supreme Court of India.)

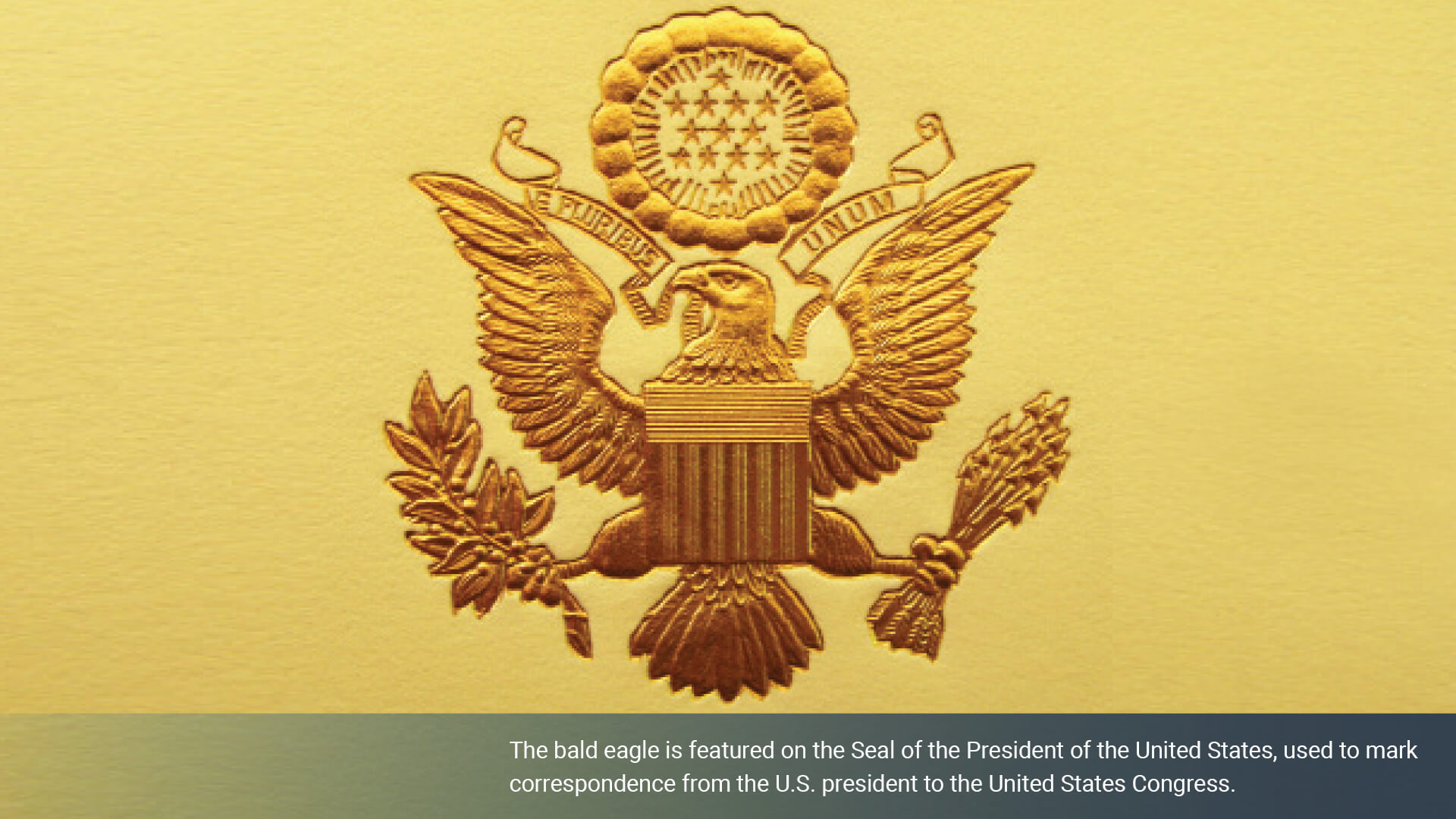

In the United States, the bald eagle is the closest we have to a sacred animal. It holds a place that no other animal does. The Founding Fathers chose the bird for the national seal in 1782. (Benjamin Franklin wasn’t wild about the choice—in a letter to his daughter, he called the bald eagle “a bird of poor moral character” because it steals food from other birds.)

For almost two and a half centuries, the eagle has been an American symbol: It’s on dollar bills, military insignia, government documents, and public buildings.

Environmental officials told Ed his land couldn’t be developed because it contained a single bald eagle nest in a pine tree.

And from the 1970s until 2007, landowners with a single bald eagle nest on their property were prevented from developing their own land. That’s because the bald eagle was on the Endangered Species list— initially for good reason: The eagle had almost disappeared in the lower 48 states. But in 1999, President Bill Clinton celebrated the bird’s recovery and announced the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service would take the bald eagle off the Endangered Species list. There was no longer a rational reason to protect the bird as endangered.

But the agency never removed the bald eagle from the list. No one in the government, it seemed, was willing to actually remove legal protections for America’s national bird, even if it no longer needed those protections.

And even if some landowners were paying a high price.

Property Owners in the Crosshairs

ED CONTOSKI HAD a problem.

He was a 69-year-old urban planner who loved the outdoors, and he wanted to retire. He owned 18 lakeside acres in Central Minnesota. If he sold half to developers to turn into residential lots, it would bring him a good amount of money.

But environmental officials told Ed his land couldn’t be developed because it contained a single bald eagle nest in a pine tree. True, the nest was empty—but an eagle might return one day, the officials said.

This was back in 2005. At the time, the Endangered Species Act (ESA) discouraged human activity within 330 feet of bald eagle nests. “Disturbing” a bald eagle came with a $100,000 fine and/or a year in jail, with the potential to double or triple for any combination of eagles, eggs, and chicks. (The law was vague: What counted as “disturbing” a bald eagle was hard to determine, but the penalties alone discouraged anyone from finding out.)

In other words, Ed had land but couldn’t use it. “I can’t even cut firewood,” he later told The Washington Post. “I can’t trim a tree. I can’t do anything.” The government had effectively turned his property into a bald eagle reserve—over one empty nest.

The Not-So-Endangered Eagle

BY THIS POINT, the bald eagle had been on the Endangered Species list for more than 30 years. When Congress passed the ESA in 1973, the bald eagle was among the first species listed under the new law’s protections. It made sense at the time: When the bird was chosen as the symbol of the United States in 1782, there were an estimated 100,000 bald eagles in the lower 48 United States. But over the years, the population dwindled to almost nothing. (Poaching was one cause of the precipitous decline: Bald eagles prey on chickens and other domestic livestock and can wreak havoc on ranchers’ inventories. The eagles were once openly considered such a nuisance that in 1917 the government offered a bounty of a dollar per dead eagle. This resulted in over 120,000 confirmed kills.)

By 1963, only a few hundred bald eagles remained in the lower 48 (though they remained plentiful in Alaska). So, when Congress and federal regulators went looking for a “poster child” for the newly enacted ESA, the eagle was a no-brainer. After all, who could argue against enhanced protections for one of our most cherished national symbols?

Source: Library of Congress

The eagles were once openly considered such a nuisance that in 1917 the government offered a bounty of a dollar per dead eagle. This resulted in over 120,000 confirmed kills.

The protections seemed to work: Through a combination of public and private efforts, the bald eagle population made a miraculous comeback. By the late 1990s, the recovery effort had been so successful that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) was ready to delist the bird.

But despite setting deadlines, the agency didn’t follow through. Year after year, the bird remained on the list.

Meanwhile, the resurgent bald eagle population vastly increased the amount of potential habitat lands that would be subject to ESA regulations. A 2007 paper from the Reason Foundation estimated that the amount of land that was “stringently regulated” due to the presence of bald eagles was 5.6 million acres—roughly the size of New Jersey.

Source: Getty

Members of Congress who supported the ESA were unhappy to see the law used as a weapon preventing regular people from using their own land.

This dynamic pretty much guaranteed ongoing conflicts between private property owners and federal wildlife regulators. In fact, members of Congress who supported the ESA were unhappy to see the law used as a weapon preventing regular people from using their own land.

“Our concept of the Act and what it was supposed to do, was, fundamentally, deal with a site-specific problem—a road, a bridge, or a dam,” said Senator Mark Hatfield of Oregon, who had voted for the ESA. “We never conceived of it being applied to millions of acres of public and private land that involves literally tens of thousands of people.”

Filing a Federal Lawsuit

TO ED, WHO CAME TO Pacific Legal Foundation with his story in 2005, it was a matter of fundamental property rights.

His lakefront land had been in his family since 1939—and his family, including him, had been diligently paying property taxes on the land every year.

“It’s unfair that we pay taxes all these years and now we can’t recoup that,” he told The Washington Post. “If it’s public benefit, let the federal government or the state pay us for it.”

Even ESPN reported on the lawsuit, accusing PLF of “wag[ing] war against environmental regulation” by trying to delist the “eagle with the piercing stare [that] has symbolized America and freedom itself in almost every imaginable way.”

Ed passed away in 2020. Back when we met him, he was a strong-willed libertarian who’d been writing and speaking about government overreach since the 1970s. (When he met with The Washington Post, the newspaper noted that Ed refused to buckle his seatbelt. Seatbelt laws infuriated him. “I’ll be [expletive] if I’ll wear it if the government insists,” he told the Post.)

Ed was determined to defend his rights as a landowner, and PLF was determined to help him—despite knowing we’d draw backlash from people who felt it was un-American to remove legal protections for the bald eagle.

“It’s the national symbol,” an endangered species advocate for the Environmental Defense Fund reminded The New York Times after PLF filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on Ed’s behalf. Even ESPN reported on the lawsuit, accusing PLF of “wag[ing] war against environmental regulation” by trying to delist the “eagle with the piercing stare [that] has symbolized America and freedom itself in almost every imaginable way.”

When PLF took up Ed’s case, we found the FWS was ignoring the deadlines they’d been given. Bureaucracies are slow-moving by nature—especially with something they don’t want to follow through on.

But with tens of thousands of bald eagles now making a home in the lower 48 states, landowners like Ed were bearing the costly burden of the government’s delinquency. They had a right to use their property. The Constitution protects individual property owners from government takings, Ed told the Post. “It doesn’t say, ‘unless eagles need a home.’”

By filing a lawsuit, we could force the government to follow its own deadlines—and get rid of an irrational restriction.

The Result of the Case…

IN AUGUST 2006, WE SCORED A VICTORY: A district court judge ruled the government needed to remove the bald eagle from the Endangered Species list by February 16, 2007, or provide reasoning why further delays were necessary.

With the delisting now unavoidable, environmentalist groups moved to declare the recovery of the bald eagle population a success story. Some even gave a nod to Ed Contoski for getting the government to finally recognize the bald eagle was no longer endangered. A lawyer for the National Wildlife Federation said Ed deserved credit “for getting a deadline imposed.“

Meanwhile, PLF took on other Endangered Species Act cases. A decade after we represented Ed Contoski, we sued the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on behalf of Louisiana landowner Edward Poitevent, whose land had been declared a “critical habitat” for the endangered dusky gopher frog—despite the frog not being spotted in the entire state of Louisiana, let alone on Edward’s land. In 2018, we won that case at the Supreme Court. It was yet another victory for property rights, and another reminder to the government that it can’t use the Endangered Species Act to reserve private property for animals who don’t even need it. ♦

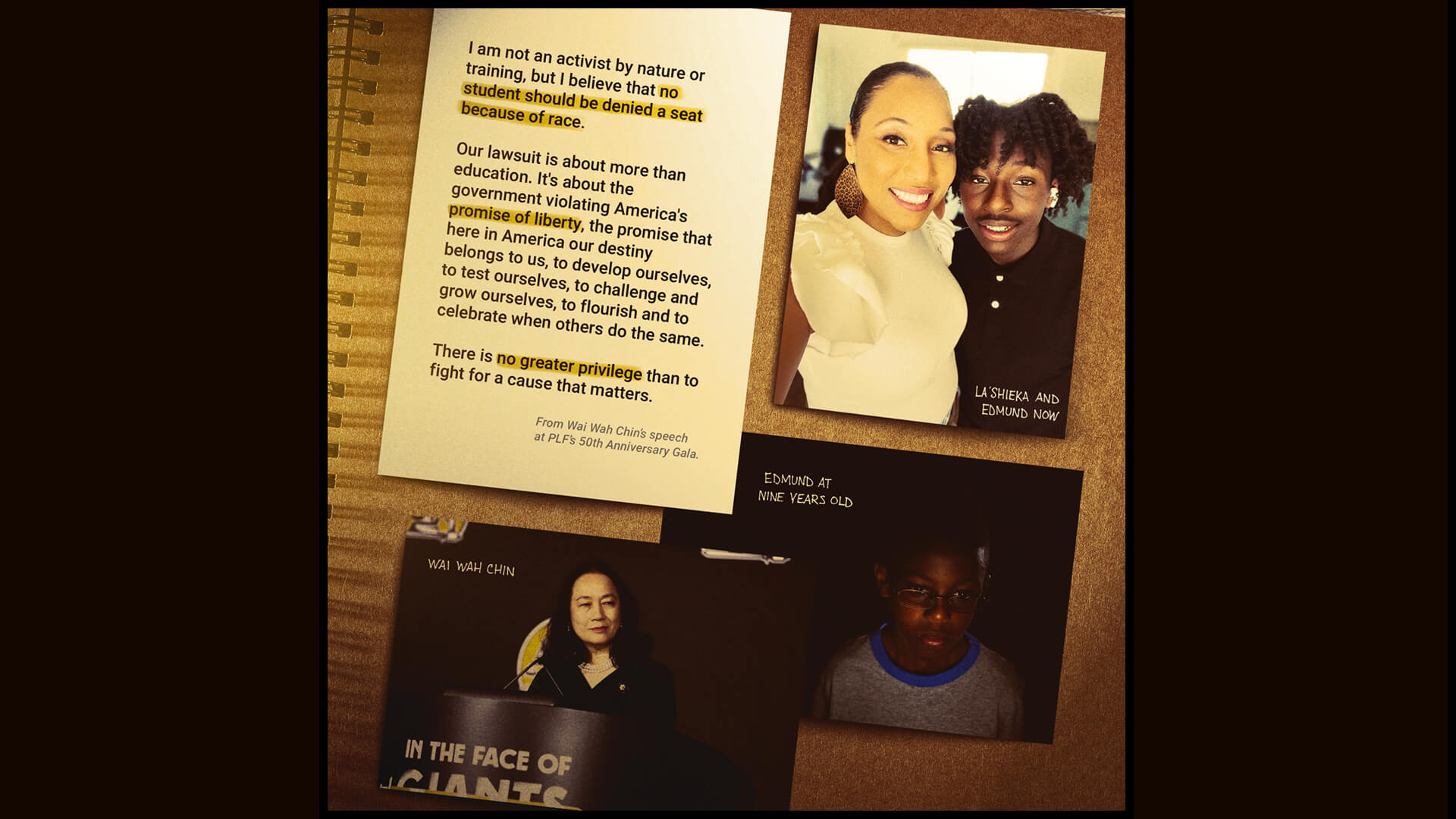

St. Louis Mom Battles Race-Conscious Education Policy

Joshua Thompson

Director of Legal Operations

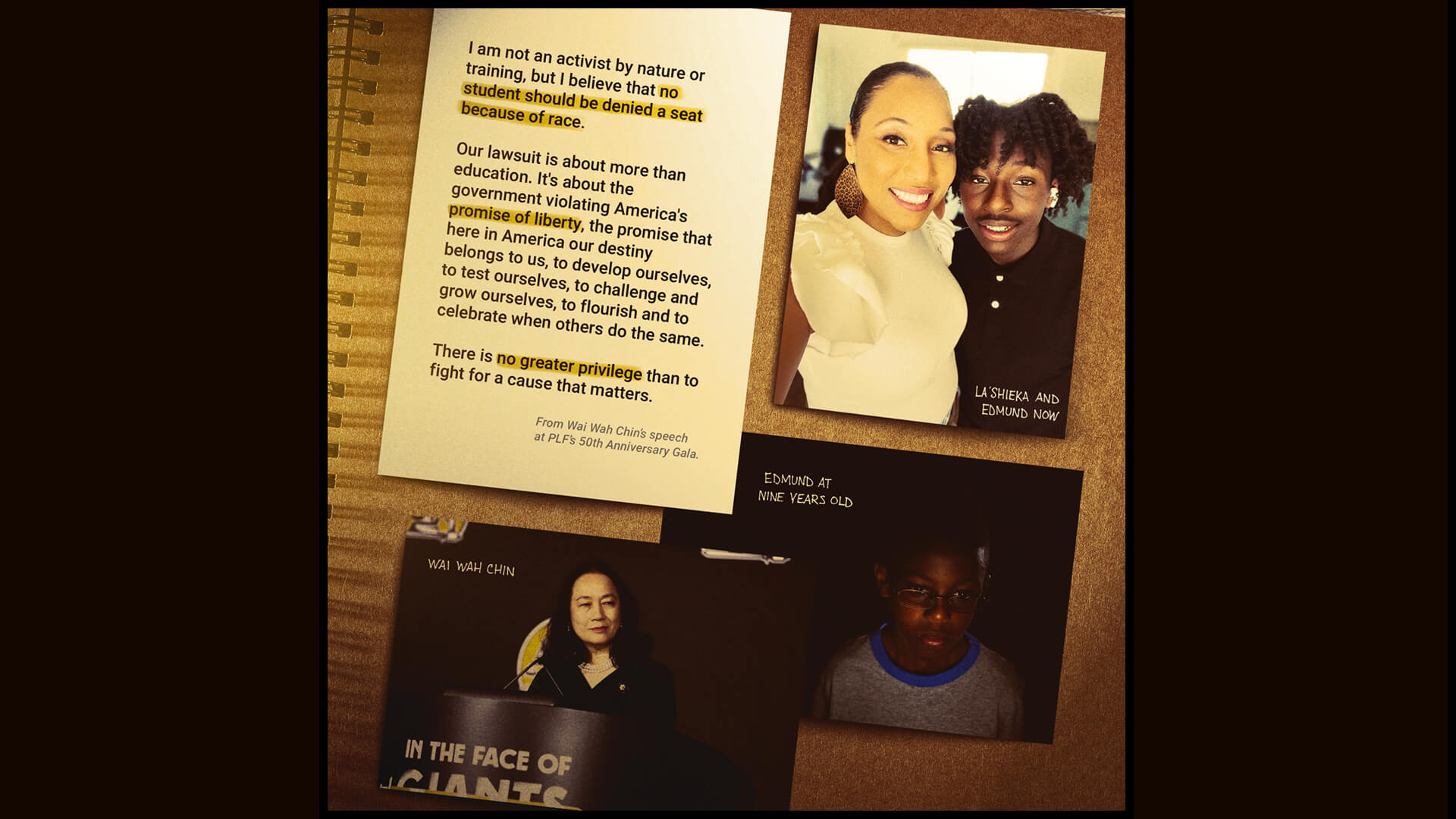

IMAGINE TELLING A NINE-YEAR-OLD he can’t continue at his elementary school because of the color of his skin.

That’s a conversation St. Louis mom La’Shieka White had with her son Edmund Lee, not during the Jim Crow era but in 2016. St. Louis policy demanded that black students be treated differently than white students in the name of racial balancing, and Edmund was paying the price.

When you talk to La’Shieka now, in 2023, she seems to smile almost constantly. Life has been good. Edmund is now sixteen and a half and learning how to drive. “We already started doing college visits,” La’Shieka says, shaking her head like she can’t believe it. Edmund is the only kid she knows who thinks high school chemistry class is easy. “It just comes to him,” she says, beaming.

A parent may be forced to explain to a child that, according to the law, their race matters.

But seven years ago, when I first met La’Shieka, she was understandably upset.

What happened to Edmund Lee and his family is a story about good intentions gone wrong. It should be a lesson for anyone who crusades to use the force of government to engineer racial equity: Any time you enshrine racial classifications into the law and dispense opportunities or barriers based on race, you’re creating a situation where a real human being like Edmund will one day be hurt.

And a parent may be forced to explain to a child that, according to the law, their race matters.

Leaving St. Louis

FOR YEARS WHEN EDMUND was young, his stepfather worked as a St. Louis police officer. That meant the family had to live within city limits, which was hard, especially for Edmund and his two younger siblings. They were in a two-bedroom apartment with no yard. Neighborhood crime was on the rise.

“Our kids couldn’t play across the street at the playground,” La’Shieka remembers, “because people would gun the stop sign.”

Shortly before Christmas 2015, someone broke into the family car. That was the last straw. Edmund’s stepfather got a new job, and in the spring of 2016, the family purchased a new home in a leafy suburb of St. Louis. The house had a yard. There were no gunshots.

“We worked really hard to get out of the city,” La’Shieka remembers.

The only drawback to the move, La’Shieka thought at the time, was that Edmund would probably have to leave Gateway Science Academy, the St. Louis charter school he’d attended since kindergarten. Edmund was a gifted kid, and at Gateway, an acclaimed STEM school, he had a 3.8 grade point average. He also had a tight circle of friends. “Kindergarten to third grade, that’s almost your whole little life right there,” La’Shieka muses.

Then, suddenly, it seemed like Edmund wouldn’t have to say goodbye to his Gateway friends after all: Another Gateway parent, whose family was also moving to the suburbs, told La’Shieka that St. Louis County policy allowed suburban students to transfer to city schools. We filled out the paperwork to stay at Gateway, the other parent told La’Shieka. You should too.

La’Shieka was thrilled—until she got the paperwork and read it over.

“I was like: Ohhh. I can’t transfer, but you can,” she remembers.

The other family was white. St. Louis County allowed only white students to transfer from suburban schools to city schools.

And Edmund is black. “I was livid, to say the least,” La’Shieka says.

A Desegregation Policy

BROWN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION ENDED formal segregation of schools in 1954. But in St. Louis, as in many American cities, neighborhoods and public schools remained largely segregated. It wasn’t—and still isn’t—an easy problem to solve. A 2020 Harvard study found that the majority of American parents are in favor of more integrated schools, yet they make personal choices that exacerbate segregation.

In St. Louis, the solution was to carve out a pathway for black city students to transfer into suburban schools while allowing non-black suburban students to transfer into city schools.

Technically, the policy that affected Edmund dated back to 1999; but it came out of a settlement agreement from even earlier, in 1983, before La’Shieka was even born. It didn’t reflect the current realities of St. Louis. “The dynamic is completely different than what it was 30-plus years ago,” La’Shieka says. In 2015, more black families were living in the suburbs; meanwhile some city schools, including Gateway Science Academy, were now majority white.

But the real problem with the policy wasn’t that it was outdated. It was that it entrenched racial identity as the deciding factor in whether children could be enrolled at a school or not. “The goal was to try to balance the racial makeup of the city and county schools,” the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education later explained in a defensive statement. But racial balancing required giving black and white students different levels of freedom. For Edmund, the policy meant he’d have to leave Gateway

Edmund’s parents had done everything they could to set him up for a bright future— putting him into a charter school, moving him into a safer neighborhood—but because their son is black, they were coming up against a government barrier.

while white peers with the same circumstances, same ZIP Code, would be allowed to stay.

“It wasn’t because we moved. It was simply because of the way that he was born,” La’Shieka says. “And it really put a fire under me.”

She decided to make some noise. She created a petition on Change.org under the heading, “Don’t let race determine my son’s enrollment.”

“Not admitting Edmund simply because he is African American is just wrong,” she wrote in the petition. “We are going to show Edmund that his parents, school, community, and people across the country will fight for what is right.”

Within hours of posting it, the petition had 20,000 signatures.

PLF Reaches Out

IT WAS THE PETITION that brought Edmund’s story to my attention.

La’Shieka started giving interviews about the petition: first to her local Fox affiliate, then to national outlets. The petition grew to over 100,000 signatures.

Lawyers began to reach out to La’Shieka about filing a lawsuit.

“One was like, ‘We’ll charge you $25,000,’” she remembers. “And I’m like, ‘I just bought a home. There’s no way.’”

I sent La’Shieka a letter, explaining that Pacific Legal Foundation was interested in representing Edmund free of charge.

At the time, PLF had never taken on a case involving K-12 education. It’s a fraught area of public policy and law, with competing governing interests and high stakes.

But I’d read Edmund’s story. Here was a clear-cut example of the government treating students differently based on race. Edmund’s parents had done everything they could to set him up for a bright future—putting him into a charter school, moving him into a safer neighborhood—but because their son is black, they were coming up against a government barrier.

La’Shieka answered my letter. Edmund became PLF’s first client in a K-12 discrimination case.

Fighting for Families

IT HAS BEEN SEVEN YEARS since we took on Edmund’s case—a case that we tried, but failed, to bring to the Supreme Court.

For PLF, Edmund’s case opened up a new area of practice. We began representing students and parents in other K-12 discrimination cases: in Connecticut, New York, Virginia, and Maryland.

Not everyone was happy to see PLF representing students like Edmund.

In Connecticut, especially, we faced hostility. There, just as in Edmund’s case, black students were being denied spots at schools because of a desegregation policy. When PLF got involved, the NAACP launched a smear campaign: It circulated a flyer accusing PLF of being “involved with numerous cases that have hurt people of color.” The ACLU accused PLF of trying to preserve segregation. The message to black parents was clear: Stay away from PLF; don’t let them represent you.

As one Connecticut mom, Gwen Samuels, put it: “They were saying there’s this conservative group, they’ve got a hidden agenda.” She added: “I get offended when people tell me that. Because if you say it’s hidden, that means you think I can’t read.” When an NAACP attorney criticized PLF at a panel, another mom, LaShawn Robinson, jumped in: “First of all, we parents hire who the hell we want to hire.”

Looking back on her son’s case, the case that started it all, La’Shieka White calls herself “really blessed to get Pacific Legal behind me.” She remembers what it felt like when PLF offered to work with her family:

Here we are, just moved into our new house. We’re worried about how we’re going to deal with this huge issue. We maybe don’t have the money to do it. You feel less-than. Then here you guys come, saying, ‘Hey, we’ll pick up some of the pieces if you fight with us.’ It helped me realize that my voice is so much more powerful than what I think.

The Result of the Case…

WE LOST EDMUND’S CASE IN COURT. But the court eventually clarified that charter schools like Gateway Science Academy would be exempt from the desegregation policy going forward.

Edmund left Gateway Science Academy while the case was being litigated and has been attending school in his local suburban district. He missed Gateway’s rigorous schedule, but he made new friends and continued to excel. What happened to him as a third-grader made an impression on him—in a good way. He saw his mom stand up for his rights. Now that he’s a teenager, his friends sometimes Google his name and stumble onto the case. He’s even had teachers discuss the case in history class. Edmund answers their questions, telling them what it felt like when he and his mom were doing interviews together, speaking about equality under the law.

As for La’Shieka, even though the lawsuit didn’t end in a legal victory, she recognizes the effect of her son’s case on other families. She says, “I really feel like we opened the door for people to say, ‘Hey, I think PLF can help us, and I think we can win.’” ♦

A PLF Attorney Fights for the Forgotten

Nicole Yeatman

Managing Editor

ON THE LAST DAY OF the Supreme Court term, PLF senior attorney Christina Martin stood in front of the nine Justices and laid out a devastating case against Hennepin County, Minnesota. The county was trying to “redefine private property by statute,” Christina said, her voice clear and deliberate.

When the county seized and sold the Minneapolis condo of Geraldine Tyler, an elderly grandmother, to settle her property tax debt, it should have refunded Geraldine the excess profit from the sale above the amount of her debt. Instead, it kept everything. The government was presuming “an unlimited power” to confiscate property to settle debts, “no matter how valuable the property or how small the debt,” Christina said.

Her words seemed to make an impression with the Court. When the county’s attorney—a former solicitor general—got up to speak, the Justices grilled him.

Are there any limits on the government’s debt-collecting power? Justice Elena Kagan wanted to know. “I mean, $5,000 tax debt, $5 million house. Take the house, don’t give back the rest?”

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson asked whether the government could take a $100,000 bank account to settle a $10,000 income tax debt. And Justice Amy Coney Barrett wanted to know: “What about the hypothetical of, you owe $20 of parking tickets? Can the state just take your whole car?”

Chief Justice John Roberts put it succinctly when he asked the county attorney, “Is your theory that the state can define property as it wishes?”

This—watching the Supreme Court Justices try to wrap their heads around home equity theft—was a moment Christina had been working toward for years.

A Bold Attitude

THE FIRST CASE Christina Martin ever argued in court wasn’t big enough to catch most public interest attorneys’ attention. It was about a ticket on a car.

Christina was a young Pacific Legal Foundation attorney in her first real legal job. She’d moved cross-country from Oregon to Florida for “her dream job.” One day she came across an inquiry from a prospective client: A man in Alexandria, Virginia, had been ticketed for putting a “For Sale” sign on his car, which many cities expressly forbid.

This—watching the Supreme Court Justices try to wrap their heads around home equity theft—was a moment Christina had been working toward for years.

To Christina, the ticket was a clear free speech violation.

“I was like, ‘Aren’t we in America?’” she says. “I mean, you can’t put a ‘For Sale’ on your own car?”

She took on the case and won. “That was a lot of fun,” she remembers. “We really ruffled some feathers in Alexandria.”

Talking to Christina now, years later, it’s clear she still has the same approach as when she argued that “For Sale” case years ago. If she stumbles onto something that strikes her as wrong, she’ll turn her full attention onto it, even if other people are inclined to ignore it. She talks animatedly about her cases.

Here was a veteran in the most vulnerable time of his life—widowed and struggling with dementia—and his own government had taken everything from him over a small unpaid tax bill.

Injustice bugs her. She can’t stand seeing government authorities push people around.

It’s that attitude that brought Christina to the problem of home equity theft.

‘Left with Nothing’

CHRISTINA HAD BEEN WORKING at PLF for about a year and a half when, in September 2013, The Washington Post published a long investigation into the curious case of Benjamin Coleman. The headline was stark: “Left with Nothing.”

Benjamin, an elderly ex-Marine with dementia, had forgotten to pay the tax bill on his Washington, DC, home. The District of Columbia placed a lien on the property, then sold the lien to a private investor. Benjamin’s home, valued at $197,000, now belonged to the private investor—“all because he didn’t pay a $134 property tax bill,” The Washington Post emphasized.

Christina was appalled when she read about what happened to Benjamin. “In the story, he was on his front porch, confused about why he couldn’t get into his own home,” she remembers. Here was a veteran in the most vulnerable time of his life—widowed and struggling with dementia—and his own government had taken everything from him over a small unpaid tax bill.

“That’s stealing,” Christina says.

The Post’s 10-month investigation had uncovered hundreds of District homeowners who, like Benjamin, lost their homes over tax debts of less than $1,000. Several of these homeowners, including Benjamin, filed a class-action lawsuit against the District in 2014.

Christina wanted to file an amicus brief in support of the lawsuit. But when she spoke to others at PLF, they were initially more hesitant.

“At the time, she was a relatively young attorney,” Larry Salzman, now director of litigation at PLF, explains. “So this younger attorney is saying, ‘I found this thing that seems crazy.’ There was some skepticism. There was a lot of: Let’s fact-check this and make sure what’s happening is what we think is happening.”

“Everyone’s always thinking, ‘There’s got to be more to the story,’” Christina says. “But as it turned out, there really wasn’t.”

The District of Columbia was trying to argue that homeowners who fail to pay property taxes on time forfeit their property rights.

As Christina suspected, the District of Columbia had blatantly violated Benjamin’s Fifth Amendment rights by failing to pay “just compensation” for taking his home. The Just Compensation Clause compels the government to pay a fair price whenever it takes private property for public use. In other words, if the government takes a $200,000 home to satisfy a $1,000 tax debt, it needs to compensate the homeowner for the $199,000 in home equity he’ll be losing. Otherwise, the government is simply stealing.

Once others at PLF saw that Christina had gotten the facts right, they gave her the green light to get involved.

“At that point, everyone understood: Wow, this is incredible that this is happening to people,” Larry says.

The District of Columbia was trying to argue that homeowners who fail to pay property taxes on time forfeit their property rights. But in her blistering amicus brief, Christina said that “[I]f states and the federal government were allowed the final say on what constitutes a valid forfeiture of constitutional rights, then government would find it all too easy to take property—indeed, all rights—from the public.”

Christina also pointed out that by stealing from “politically powerless” residents like Benjamin, the city had failed “the chief object of government: the protection of individual liberties and property.”

Christina’s amicus brief in Coleman v. District of Columbia caused a stir. Suddenly, a national organization was paying attention to a problem that only legal aid lawyers and class-action firms previously seemed to care about. The Washington Post editorial board cited Christina and her PLF colleague Todd Gaziano when it urged DC to “do the right thing.”

Meanwhile, a couple of Michigan lawyers started talking to PLF about similar cases. This wasn’t just a DC problem. This was happening all over the country.

‘Their Jaws Dropped’

ACROSS THE DOZEN STATES that allow local governments to keep surplus value from tax foreclosures, roughly three homes a day are seized.

That means every single day, three American families are grappling with the loss of their most valuable asset. Most of them have no idea, until it’s too late, that a delayed tax payment could leave them homeless.

After Christina took on two Michigan cases—including Rafaeli, in which an elderly man lost his home because he underpaid his tax bill by $8—she started getting emails from people all over the country who’d had their homes taken. Some of them weren’t even seeking legal help. “Some were just sharing their stories,” Christina remembers. It was cathartic for them. One woman told Christina she’d been a child when the government took her family’s home.

Christina started working with PLF’s legal policy and strategic research teams to pinpoint exactly which state laws allowed home equity theft.

“She was relentless,” Larry remembers. “She kept pushing the scope of the project wider: more states, more cases.”

At one point, Christina found herself at a Montana property rights conference with a captive audience of state legislators. She was scheduled to speak about a different property rights issue—but she knew Montana was one of the states that allowed home equity theft. She couldn’t let the opportunity go by.

She told the audience about the Rafaeli case in Michigan. Then she added: “But before you start to judge the government in Michigan, you need to look at home. Because Montana’s doing the same thing.”

Their jaws dropped.

Afterward, a state senator approached Christina. “We need to fix this,” he told her. He meant it. PLF’s legal policy team helped the senator draft a bill to end home equity theft in Montana, and the bill passed.

Shortly afterward, the Michigan Supreme Court handed PLF a victory in Rafaeli—a victory that meant Michigan counties would no longer be able to keep surplus proceeds from tax foreclosure sales.

That win brought even more cases to Christina, with more victims hopeful that PLF could undo the injustice they’d suffered.

Fighting for the Forgotten

THE PEOPLE HARMED by home equity theft are basically forgotten by society, Christina says. “They don’t have a voice, typically. They don’t have money. They can’t hire lawyers. They don’t know their rights. They’re just forgotten.”

In the past couple of years, she and PLF have represented a Massachusetts woman forced to live in her car after her home was taken, a farmer about to lose 34 acres of land, a nurse whose home was sold by a shady government-connected non-profit, and two brothers fighting to save the house their parents left them.

And, of course, 94-year-old grandmother Geraldine Tyler, whose case Christina brought to the Supreme Court.

Remarkably, in the Tyler case, the county defended its conduct in its briefs by pointing to a 13th-century law that allowed feudal lords to take their tenants’ land if “quit-rents” were not paid on time.

But Geraldine Tyler “was not a vassal owing fealty to her lord but a modern-day fee simple owner of real property,” PLF wrote in our reply brief. It was such a strong riposte to the county’s argument that Justice Neil Gorsuch pulled out the brief and read the line out loud during oral arguments.

The Result of the Case…

JUST BEFORE THIS MAGAZINE WENT TO PRINT, the Supreme Court announced its decision in Tyler v. Hennepin County: A unanimous ruling that home equity theft is unconstitutional.

“Minnesota may not extinguish a property interest that it recognizes everywhere else to avoid paying just compensation when it is the one doing the taking,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the decision. He quoted his own 2021 opinion in Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid, another PLF Supreme Court victory: “[P]roperty rights cannot be so easily manipulated.”

Now states will have to change their laws to comply with the Tyler ruling. They’ll no longer get away with pocketing windfall profits from tax foreclosures.

Three years ago, in 2020, Christina told PLF’s leadership that she wanted to end home equity theft in five years. “And I meant it,” she says. “I believed it. Because I’m at Pacific Legal Foundation, and we can actually get to the Supreme Court.”

And now, she says, “here we are.” ♦

A Risky Gambit: The Inside Story of PLF’s Student Loan Lawsuit

Frank Garrison

Attorney

THE ADMINISTRATION WAS BEING sneaky from the start.

From the moment President Joe Biden announced the student loan forgiveness program on August 24, 2022, it set off alarm bells. The president said the Department of Education would automatically cancel $10,000 to $20,000 in student debt for millions of Americans. Estimates pegged the total cost of the program at $500 billion—a staggering number. Clearly, President Biden was trying to fulfill a promise he’d made on the campaign trail, no matter how high the price tag.

There was news buzzing through Congress: The administration, it seemed, was planning to completely sidestep all regulatory procedures for student loan forgiveness.

The initial press release and shoddily written FAQ were sketchy on details about how, legally, the forgiveness program would work. The Department of Education’s power to forgive the debt ostensibly came from a 20-year-old law, the HEROES Act. But as that law’s drafters made clear, it was intended to help veterans and their families—not to give the executive branch a roving license to arrange handouts for every American with student debt.

“The Biden administration has to know it lacks the authority to unilaterally cancel a half-trillion dollars in student debt,” The Wall Street Journal said.

At Pacific Legal Foundation, we immediately knew the program was unconstitutional. In our early conversations after the program was announced, “everyone had the assumption that this is illegal,” my colleague Caleb Kruckenberg remembers. “The HEROES Act doesn’t do what they say it does. But what are we going to do? Who’s going to challenge it?”

After the Biden administration’s press release, we waited for a formal announcement from the Department of Education—because that’s usually how things work: The government announces it’s going to do something, then follows up by taking formal regulatory steps. Without a formal rulemaking, it’s hard to challenge something in court.

“We were expecting them to do a proper process,” my colleague Michael Poon remembers. “An orderly process.”

So we waited—and a couple weeks went by.

Two Weeks to File

CALEB WAS THE ONE who figured it out.

“I had a meeting on the Hill,” Caleb says. There was news buzzing through Congress: The administration, it seemed, was planning to completely sidestep all regulatory procedures for student loan forgiveness.

“That’s when we realized: They weren’t going to issue a formal thing,” Caleb says. “They were planning to initiate the program in October, as soon as October 1. They were just going to do it. And then they were going to go, ‘Look what we just did.’”

By this point it was mid-September. In as little as two weeks, the Biden administration would spend billions on an unprecedented debt forgiveness program, without congressional approval or any formal regulatory review.

“We realized: We have to scramble to stop this,” Caleb says.

It was a crazy moment. We all knew that if the administration successfully disbursed the funds in October, challenges to the program would likely be fruitless.

“Once it goes through, there’s nothing you can do,” Caleb says. “We can’t take back the money. There are due process problems.”

This seems to have been the administration’s plan all along: to be vague enough that it could rush into launching the debt forgiveness before anyone could challenge the program in court. It was a deliberate plan to avoid challenge—because even among the president’s own supporters, the program was deeply unpopular. Bills with similar programs had been proposed in both the House and Senate but had gone nowhere. By announcing the program through a press release, and trying to rush to spend the money, the Biden administration was essentially saying: We’re going to do it anyway, because you’re not going to be able to stop us.

At this point, of course, PLF was eager to file a lawsuit—but we needed a client, someone with standing to sue. That created its own challenges: To have standing to challenge a government program, you need to show how you’d be injured by the program. Here, the federal government was giving out free money. Who could show that they were harmed by it? And how could we find that person before October?

My Strange Role in the Lawsuit

THIS IS A GOOD TIME to mention that I live in Indiana.

A few years ago, Indiana changed its laws to make loan forgiveness taxable as income. A few other states have similar laws.

I should also mention that, as an attorney who has spent his career working at non-profits, the balance of my student loan debt will be forgiven in about four years through the federal Public Service Loan Forgiveness program. That program, unlike Biden’s proposal, was passed by Congress. (It was signed by President George W. Bush in 2007.) Indiana will not tax me on my public service loan cancellation because it’s grandfathered into the law.

This seems to have been the administration’s plan all along: to be vague enough that it could rush into launching the debt forgiveness before anyone could challenge the program in court.

But the Biden loan forgiveness would be a different story.

The Biden administration was planning to automatically forgive $20,000 of my student debt. Indiana would then tax me on that $20,000—meaning I’d be on the hook to pay about a thousand dollars extra in taxes for forgiveness I didn’t ask for and that wouldn’t help me.

I brought it up at a meeting with the other attorneys. The student loan forgiveness program is going to personally cost me a thousand dollars, I told the other attorneys. Maybe we can find someone in my situation to bring a case.

I didn’t really intend for me to be the client. As an attorney, you want to make a name for yourself by bringing cases, not by being the client in a case. But things were moving so fast. We were witnessing an egregious violation of the separation of powers, and we had such a short amount of time to challenge it.

My colleagues immediately began spit-balling: Could PLF represent one of its own attorneys?

“The default mood was like, ‘We’re not going to represent Frank,’” Michael remembers. “But Caleb and I were raring to go. We were like, ‘Well, why can’t we? Why shouldn’t we do this in the next week?’”

“This was the needle in the haystack,” Caleb says.

Once the team decided PLF could represent me, and it seemed clear we didn’t have time to find anyone else, I agreed to be the plaintiff.

That was on September 20. Now the countdown clock until October was on.

The Center of a National Storm

FOR A WEEK, Caleb and Michael worked at a frantic pace to draft our complaint and a motion for preliminary injunction. I gave them access to all the personal information they needed.

“We worked all day and night for seven days,” Michael remembers. He was working out of his home in Utah; Caleb was in DC; and I was in Indiana. We coordinated by chat and video calls.

It was an odd experience, as an attorney, to suddenly become a client. I had a window into what it feels like to open up your life so that your story can become the basis for legal action. It’s unnerving—and it gave me tremendous respect for every PLF client.

We filed the lawsuit only a few short days before October, on Tuesday, September 27, 2022. My face was suddenly on Fox News. Caleb had to travel to Colorado that day to argue a different case before the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals. “I did Megyn Kelly’s show that night from Denver,” Caleb remembers.

Our lawsuit was major national news. We immediately got hate messages from people who wanted their loans forgiven. After appearing on television, Caleb got phone calls and emails, including messages like, I hope you die. I’m going to come after your family.

I was getting hateful messages too, mostly on Twitter. I shut down my account.

Meanwhile, White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre was asked about our lawsuit in her daily briefing. She denied that people like me would automatically get their loans forgiven—even though that’s what the government’s own website said.

The next day, on September 28, Caleb checked the website again. Someone had changed it overnight: Now, it said people like me could opt out of forgiveness.

The Biden administration was deliberately changing the rules of their program on the fly to sidestep our lawsuit. “It was insulting,” Caleb says. “Once we sued, it was all a big game. They’d change it just enough to make sure we couldn’t sue. They’d update the FAQ all throughout. Because it’s all fake. It’s not a law, it’s not a regulation. They were making it up as they went along.”

The Result of the Case…

LARGELY BECAUSE OF THE GOVERNMENT’S CHANGES TO ITS OWN PROGRAM, the district court and Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals both ruled that we’d lost our standing to sue.

But we had managed to pause the implementation of the forgiveness program at a critical time, right before the money was supposed to be disbursed. After we filed our lawsuit, a group of states filed another lawsuit. And the government put the program on indefinite hold until all legal challenges were worked out.

By the time you read this, the Supreme Court may have weighed in on the states’ lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the forgiveness program. Pacific Legal Foundation filed an amicus brief in that lawsuit on behalf of the legislators who wrote the HEROES Act and who object to its misuse.

Our staff still receive hate mail for PLF’s role in halting the loan forgiveness program before it got off the ground. When my colleague Jessica Thompson went on CNN to talk about the states’ lawsuit at the Supreme Court, she received messages so vile they can’t be excerpted here, not even partially.

So even though PLF’s lawsuit has not made it past the Seventh Circuit, was it worth it—the frantic rush to file, the sleepless nights, the hate mail?

Without a doubt.

“Our arguments were right,” Michael says. “And for a second it felt like we might be the only guys standing between Biden and $500 billion. We had to do it.”

He adds: “When something really terrible is coming down the pike, you should be biased toward action. And we were. A lot of times that means you’ll fail. But it’s important enough to try.” ♦

Welcome to PLF’s

50TH ANNIVERSARY GALA

MARCH 23, 2023

AT THE NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY

IN WASHINGTON, DC

We know that only a small fraction of our friends could travel to our gala. But each one of you was with us in spirit. Let’s take you back through the night where we celebrated the work we’ve done together…

At the start of the evening, as tourists exit the museum, you and 600 other Pacific Legal Foundation supporters, allies, and guests enter in tuxedos and gowns to take photos on the red carpet.

In an upstairs gallery, PLF offers “Bold Fashioned” and “Victory Collins” cocktails while you catch up with PLF attorneys, clients, and friends, some of whom traveled across the country for this evening.

At the sound of chimes, you walk downstairs to the atrium where the first course of dinner is waiting for you.

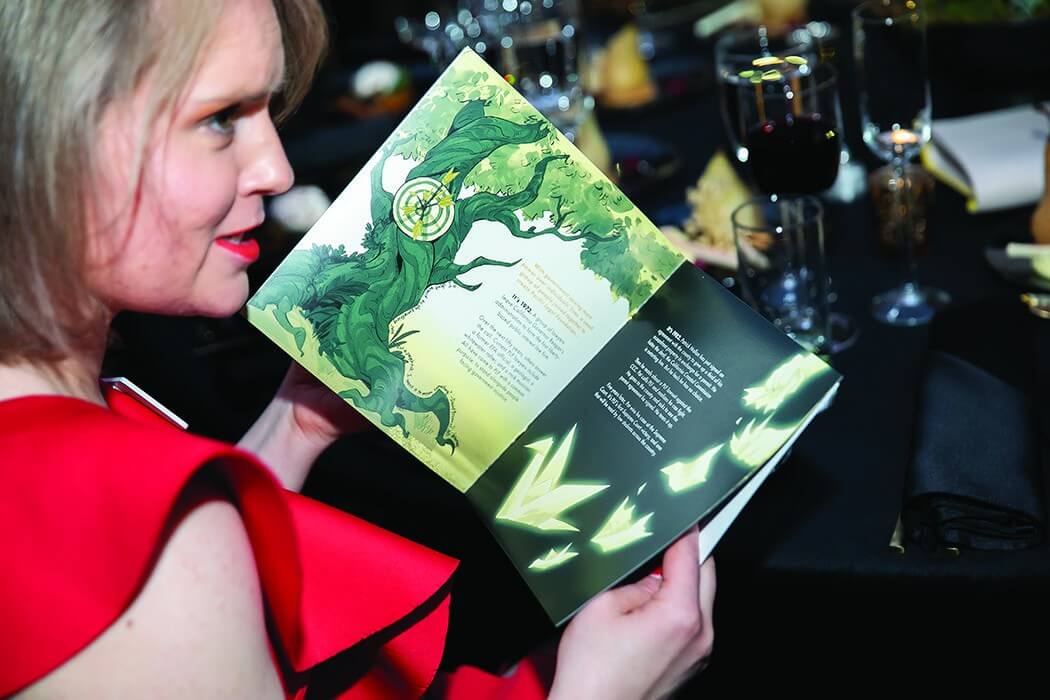

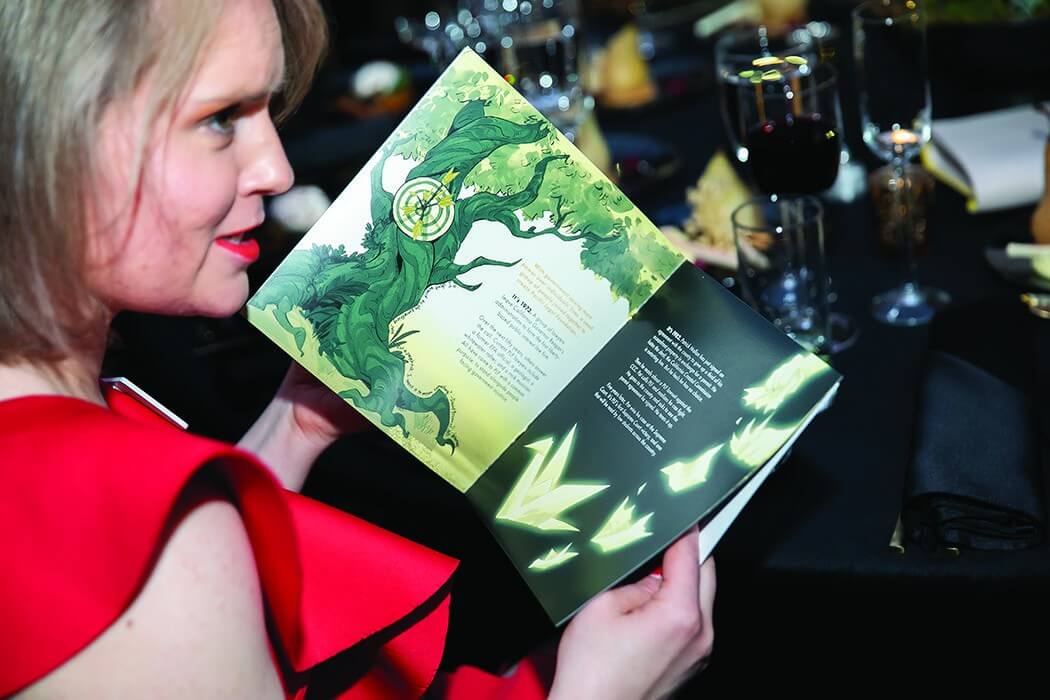

The dinner program at your seat is a 50-year adventure story: It takes you back into moments when PLF donors and clients decided to take a stand for freedom.

Tonight is not about PLF staff, president Steven D. Anderson says in his opening remarks. “It’s about those people who stand up and fight back in the face of giants against government overreach.”

Over dinner you talk with new friends at your table. Some are longtime PLF donors. Others have worked with PLF on cases and legislative efforts.

“May we continue to advance liberty together,” PLF senior attorney Christina Martin says.

As you move from the dinner table to the afterparty, you walk around the “Tree of Reflection,” which celebrates 14 PLF Supreme Court victories. (Of course, after the gala, PLF’s Supreme Court tally will quickly grow to 17.)

The crowd is energized and excited. You move through the “enchanted forest,” meeting new people.

Before you leave, you take your chance trying to pull the sword from the stone. Victory! It’s been a beautiful night with 600 people from the PLF family, all fighting for liberty.

555 Capitol Mall, Suite 1290

Sacramento, CA 95814