Spring 2024

False Dichotomies

“The smallest minority on earth is the individual.”

AYN RAND

I grew up in what I’d call an apolitical household. It’s not that my parents didn’t have a perspective; it’s just that we didn’t much get into discussions about candidates running for office—and never mind sessions on political or moral philosophy.

Early on, I wasn’t much different. But as a child of the 1980s, I was fascinated by certain characters on television: Family Ties’ Alex P. Keaton, the tie-wearing, briefcase-toting lover of Milton Friedman and Ronald Reagan, and The Dukes of Hazzard’s Boss Hogg, the tyrannical county commissioner.

My political beliefs began to develop more through high school (Norview—Class of ’92!). But it was my first year in college where things truly solidified. In one of my early days at the University of Virginia, my friend (and future best man) Josh introduced me to one of his roommates, an architecture student from New York City. In a conversation that ultimately proved pivotal in my life, he suggested I read a book about an architect in New York City: The Fountainhead by Ayn Rand. Over the next year, I devoured more Rand, Friedman, Hayek, Hazlitt, Spooner, Nock, and Nozick, among others, plus Reason, Liberty, and The Freeman magazines, understanding clearly for the first time what must be protected against all else—the rights of the individual.

I wish I could say my decision to go to law school after graduation was guided by this epiphany. (It wasn’t—I bumped into someone as I moved into my fraternity house who said he was taking the LSAT.) What I can say is that my experience in law school definitely led me to devote my professional life to ensuring each of us is seen as who we are and not what we are.

Of course, that’s easy for me to say. As you’ll read in subsequent pages, under current convention, I am the very apex of privilege—because I’m white, male, and heterosexual. Everything in my life has been unearned, blithely handed to me by a system rigged to guarantee me comfort, success, and prosperity.

Never mind that I was born to teenagers. Never mind that I first lived in a trailer park. Never mind that I’m left-handed (have you ever tried using scissors made for a right-handed world?!). Everything about me can be effortlessly deduced simply because of a few things over which I had no control.

But never mind all that—it’s a phony, formerly fringe theory that reduces all human beings to a handful of characteristics, denies us all agency, and asserts control over our destiny. The authentic truth is that we’re all unique, that each of us comes from dissimilar circumstances, and that we’re all, well, just different. Yet, at the same time, our country and Constitution were created to protect every American as an equal individual, even in those situations where a majority of like-minded (not look-alike) people choose to chart a certain path the minority would rather not travel.

I often tell our supporters that PLF’s work on equality issues is not just a professional pursuit—it’s a personal passion. As long-time readers know, I’m the father to two young boys whose features and traits hew closely to mine (with a huge assist from their mom, luckily for them). I simply refuse to have them grow up in a system where anyone—especially the government with a monopoly on force—judges them because of how they look.

Indeed, I can’t imagine a world where Boss Hogg and Rosco P. Coltrane persecuted, hounded, and harassed the Duke boys because of their chromosomal or melanin mixture instead of illegally running moonshine.

That’s the real hazard—and PLF is committed to rooting it out once and for all.

Steven D. Anderson

President & CEO

An ‘Oppressor’ Professor in California?

Nicole Yeatman

editorial director

THE PROTESTORS wouldn’t leave the field.

Football players from the University of California, Berkeley and the University of Southern California watched, confused. Their game—a nationally televised rivalry matchup—was supposed to begin. But just after the coin toss, 15 protestors stormed the 50-yard-line and ran to the center of the field.

This was Saturday, October 28, 2023. Viewers watching on TV assumed the protest was about Gaza, where Israel was retaliating for Hamas’s October 7 attacks. The protestors on the Berkeley football field certainly looked like they were protesting war: They shouted wildly, hooking their arms tightly together, ignoring the police. One young man appeared to be in tears.

The protest, it turned out, had nothing to do with Gaza. Most of the protestors were UC Berkeley students, and they were protesting the university’s decision to suspend Professor Ivonne del Valle—a woman who had admitted to stalking and harassing a male professor at another school. Why were they protesting the suspension? Because del Valle, a colonial studies professor, is a Mexican American immigrant. The man she stalked, UC Davis English professor Joshua Clover, is white.

“I don’t want UC Berkeley to think that they can do this to a minority woman in order to protect a white, senior professor,” del Valle told news site KQED.

Students took her side. Besides storming the football field, they also wrote an angry open letter to the chancellor and threatened a hunger strike.

“[F]or del Valle’s supporters,” Josh Barro writes at Substack, “the issue is not objective facts, like the contents of voicemails she left for Clover, the number of times she called his office phone line, or the tweets she posted encouraging the FBI to ask his romantic partner about him; it is del Valle’s subjective, lived experience as a Latina immigrant in a society dominated by white men.”

The Oppressor-Oppressed Framework

WHEN YOU LOOK AT the bare biographical etchings of two people’s lives—sex, age, nationality, and ethnicity—can you tell which person has a better life? Which one has more power? Who is the oppressor and who is oppressed?

Why were they protesting the suspension? Because del Valle, a colonial studies professor, is a Mexican American immigrant. The man she stalked, UC Davis English professor Joshua Clover, is white.

Some say yes, they can automatically tell. They see certain groups as oppressors and others as oppressed. For these people—many of them on college campuses and in government offices—human interactions can be understood only through this framework: by putting people into buckets based on flawed assumptions about who has power.

In The Three Languages of Politics, Arnold Kling calls the oppressor-oppressed framework the language of progressivism. “For a progressive,” Kling writes, “the highest virtue is to be on the side of the oppressed and the worst sin is to be aligned with the oppressor.”

The oppressor-oppressed framework relies on broad generalizations. If you’re white, you’re an oppressor; if you’re black or Hispanic, you’re oppressed; if you’re male, you’re an oppressor; if you’re female, you’re oppressed; if you’re a landlord, you’re an oppressor; if you’re a tenant, you’re oppressed—and so on, with every ethnicity and identity mapped out along this binary scale until the vast, dizzying diversity of human experience is reduced to a cartoon. There are good guys and bad guys, and you can tell who’s who just by looking at them.

It’s a morally inadequate way to perceive the world. What matters in this framework is not what a person does, but to which group he or she belongs. People who apply this framework “discard the idea that people are individual moral actors with responsibility for their actions,” Barro writes, “[i]nstead… awarding culpability in any conflict to the person who ranks as less oppressed, regardless of actual existing evidence about who did what and why.”

It’s the inverse of “might makes right” and it’s just as wrong. The oppressor-oppressed framework assigns the moral high ground to individuals based on a rudimentary diagnosis of certain identity groups as victims—and it doesn’t allow for the individuality and unpredictability of real human beings.

One UC Professor Stalks Another

IN THE STRANGE CASE of Ivonne del Valle and Joshua Clover, three separate university investigations concluded that del Valle stalked and harassed Clover. The two professors knew each other professionally. According to The Chronicle of Higher Education, del Valle became convinced Clover was tweeting coded references to her and had gained access to her computer—an accusation she provided no evidence for and which he denies. By her own admission, del Valle then broke into Clover’s apartment building, slid angry notes under his door, spray-painted messages in the hallway, left voicemails, sent emails to his colleagues, posted a photo of his partner online, and dumped rotten food on his mother’s doorstep. Clover had to move apartments and stop using social media to escape del Valle’s harassment.

The oppressor-oppressed framework assigns the moral high ground to individuals based on a rudimentary diagnosis of certain identity groups as victims—and it doesn’t allow for the individuality and unpredictability of real human beings.

Del Valle told KQED she was “not proud” of everything she’d done.

Clover, 61, is from Berkeley. He teaches poetry and critical theory. Del Valle is 48 and was raised in Guadalajara, Mexico. Her academic focus is colonialism in Mexico. Both professors are established in their fields at top University of California schools. They are academic peers. Most of us would see them as equal in dignity and power—and certainly, equal under the law.

For del Valle and her supporters, Clover is an oppressor and del Valle is oppressed.

After Berkeley suspended del Valle, students called for her to be “reinstated immediately” and accused the university of “victim-blaming.”

“If UC Berkeley really wants to become a Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI), it needs to start treating our Latinx professors with respect,” declared an open letter signed by more than 300 individuals and organizations.

Del Valle told her supporters at a townhall that her life’s work was being “taken away by a white person with power.”

A False Dichotomy

IN THE PEDAGOGY OF THE OPPRESSED—ranked #3 in Google’s 2016 report on most-cited social science texts—Paulo Freire writes, “Never in history has violence been initiated by the oppressed.” For those who believe in the oppressor-oppressed framework, the law can’t be neutral. They believe it needs to recognize the original sin of oppression and judge people’s actions differently based on whether they’re oppressor or oppressed.

Source: Darren Yamashita-USA TODAY Sports

That violates a core principle of a free society—that all of us, rich or poor, black or white, male or female, are equal in the eyes of the law. An individual’s actions should drive her destiny, not her status or background.

And even if you wanted to, you couldn’t divide human beings into two neat lines of powerful and powerless. We’re too messy, too dynamic, too free a species. That’s a good thing. We want people to rise and fall by their own merit, to defy expectations, to have full agency and responsibility for their lives.

The oppressor-oppressed framework is “a false dichotomy that leads to moral nihilism,” lecturer Remi Adekoya writes. “We need to abandon this morally misleading dualism of oppressor vs oppressed, in favor of a truly empathetic vision of the world in which everyone is recognized as having flaws and vulnerabilities, and is judged on their actions, not on which group they belong to.”

‘An Intellectual Rot’

THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA system, where the Ivonne del Valle saga continues to play out, happens to be where researcher J.D. Haltigan would like to get a job: He wants to work at UC Santa Cruz as a psychology professor. But he knows he won’t be hired, because the University of California system requires all applicants to submit a statement about their contributions to so-called Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. The school scores applicants’ statements on a rubric that downrates anyone who only says they’ll “invite and welcome students from all backgrounds” and will “treat all students the same.” To get a high score, applicants need to support race-based affinity groups.

Haltigan, represented by Pacific Legal Foundation, sued the school. Meanwhile he’s been writing on Substack to document what he calls “an intellectual rot” in academia. As part of his Ph.D. program, he had a mandatory cultural diversity class that taught, in Haltigan’s words,

that, (a) people ought to be best conceptualized as members of groups (i.e., racial/ethnic, gender, sexual orientation), (b) some groups are victims and some groups are oppressors, (c) the oppressors are the bad people, (d) the victims are the good people, and (e) the oppressors should be punished.

This was in a class for psychologists, Haltigan emphasized. It’s absolutely the wrong way for psychologists to view people: The central approach to clients in psychotherapy should be “to treat the individual,” Haltigan said.

A Better Framework

IN THE THREE LANGUAGES OF POLITICS, the oppressor-oppressed framework is just one that Kling identifies. Another is liberty-coercion, which values individual freedom and is skeptical of efforts to curtail it.

Kling talks about ancient stories that reinforce the oppressor-oppressed way of viewing the world. They’re fundamentally stories about opposing groups locked in a struggle.

“The cultural software that aligns with the liberty-coercion axis may not be as easily located in ancient stories,” he writes, pointing to more recent stories like Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and George Orwell’s 1984 instead. The drive to be free of coercion is more of an Enlightenment ambition.

Unlike oppressor-oppressed, the liberty-coercion framework doesn’t position groups in opposition to each other. It doesn’t put people into groups at all: It sees each human being as an individual equally accountable for his or her own actions and deserving of freedom.

And under this framework, PLF—which fights for individuals against unjust government encroachment—is on the right side of history. ♦

Extreme Depths: Two Navy Divers in a New Fight

Joshua Thompson

director of Equality and Opportunity Litigation

“I traverse the dark, forbidding depths of the world’s oceans, lakes, rivers and seas where only a select few can follow.”

From the Navy Diver Ethos

HUNG CAO AND MARTY HIERHOLZER both live in Virginia, only a few hours from each other. They have different backgrounds: Hung is of Vietnamese descent; Marty is white. Hung’s father was deputy secretary of agriculture in Vietnam. Marty’s father was stationed at Pearl Harbor in World War II. Hung’s family fled Vietnam when he was four years old, hours before the fall of Saigon. Marty’s family started a farm when he was eleven. Hung went to one of the country’s best high schools, Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology. Marty went to a normal public high school. Hung is now running for the United States Senate. Marty is disabled and running a business.

These two men, who have never met, have something in common.

They were both deep sea divers in the Navy. It’s an elite role: Navy divers work hundreds of feet below the water’s surface to conduct search and rescue operations, recover wreckage, and perform underwater repairs. The deeper they dive, the less light they have. Sometimes Navy divers work in pitch-black water, unable to see their own gauges. Sometimes they recover bodies. It’s a job few human beings can do.

Hung and Marty were among the best. Hung advanced to become commander of the Navy Diving and Salvage Training Center, where he taught the next generation of divers. Marty retired after 22 years with the rank of Master Diver, the highest rank for divers.

Now long out of the Navy, Hung and Marty have another thing in common: They’re both fighting for the government to judge people as individuals, with one set of rules for everyone.

“My personal Honor and Integrity are above reproach and compel me to do what is right regardless of the circumstances.”

From the Navy Diver Ethos

WHEN YOU’RE A NAVY DEEP SEA DIVER, things that seem important on the surface—what school you went to, or how much money your family had—fall away. What matters is what you’re capable of.

Hung was one of a thousand graduates from the U.S. Naval Academy. Of those thousand, only six were selected for special operations, which includes diving. Of those six, only Hung eventually made it to the senior rank of Captain.

“Do you think I made it because of my background?” Hung asks. “No, I made it because I’m the best at what I did. I hate to say it like that, but it is true.”

When Hung commanded the Navy Diving and Salvage Training Center, he had to cut about 75 percent of the students who came in for training. “When we’re beating you up in the water—ripping off your mask, spinning you around and stuff like that—people freak out,” he says. If you can’t make it through training without panicking, you can’t be depended on in a mission.

Hung was the final decision-maker on whether to disenroll a struggling student from the program. He would receive a stripped-down version of a student’s file: no name, no photo, no sex. He could have been looking at the file of an admiral’s son and would have no idea. His decisions were blind, based only on each student’s individual performance.

“That’s how it should be,” Hung says.

He wants the same for Thomas Jefferson High School (TJ), where, in the 1980s, Hung and his classmates were “iron sharpening iron,” as he put it in The Washington Post. The admissions process at TJ should be blind, Hung says. It should favor the most qualified applicants, regardless of background.

Hung has been speaking out against TJ’s new admissions process, which is weighted against Asian American students—currently a majority of the school, and therefore seen as having too much privilege.

“Discriminating against one minority group to benefit another minority group has no place in our society,” Hung wrote in the Post.

“The laws governing my chosen profession are absolute and unforgiving . . .”

From the Navy Diver Ethos

MARTY TRAVELED THE WORLD during his two decades in the Navy. His work included saturation diving, where you dive down to a thousand feet below the surface.

“It’s very hard on your body,” Marty says. He has back, shoulder, and knee problems; he also has tinnitus in his ears, caused by explosions and loud equipment.

After leaving the Navy, Marty went to work for a defense contractor that sold diving supplies. He couldn’t stomach it. “The company was in business for one reason only,” he says, “and that was to get as much money out of the government as they could.” He started his own business instead, MJL Enterprises. He provides equipment and administrative services to VA hospitals. The company’s motto: To serve those who serve.

The Small Business Administration sets aside some government contracts for “socially and economically disadvantaged” small businesses. Marty figured he’d apply for the program. His injuries from his Navy service qualify him for disability pay; he thought that meant the government considered him disadvantaged. Getting into the SBA’s program would allow Marty to compete for contracts he’d otherwise be barred from winning.

But Marty was rejected. Even when he explained his physical disability, he was told he’d failed to demonstrate his disadvantage in society.

Meanwhile, the government automatically considers business owners with certain racial backgrounds to be disadvantaged.

In other words, there are different rules for different people. The government sees some people as victims and some as privileged—and it doesn’t make that distinction on an individual level. Instead, it lumps people into buckets based on group identity—and even though Marty-the-individual has a physical disability, the government believes white men as a group have an advantage.

“We’ve come a long way since the Civil Rights times of the sixties to prove equality amongst all us citizens,” Marty says. “And here we have something that clearly causes divisions. And it doesn’t fit the narrative of our nation and what we stand for.”

“The accomplishments of United States Navy Deep Sea Divers are the benchmarks by which the world measures man’s achievements in the sea.”

From the Navy Diver Ethos

WHAT PIECES of a person’s life give them power? Who gets to decide?

Hung’s family was well-off when he was a toddler; then, suddenly, they weren’t. When they left Vietnam, they had only two suitcases. “Someone stole one,” Hung remembers.

Does that make Hung privileged or not? Oppressor or oppressed?

Marty is a business owner doing a job he cares about. He also suffers physical pain from the years he spent in service to his country.

Source: Hung Cao’s campaign

It’s hubris to presume you know how privileged a person is based on certain identity markers. It’s wrong to rig a set of rules because you believe certain groups have too much power.

Is he advantaged or disadvantaged? How could you possibly tell from the color of his skin?

Both Hung and Marty have lived extraordinary lives. Marty deployed to almost every country in the world. Hung was one of the divers who found and recovered the wreck of John F. Kennedy Jr.’s plane. Both men pushed themselves to excel. As divers, what mattered was their individual skill and grit. They have memories and achievements no one else on Earth has.

It’s hubris to presume you know how privileged a person is based on certain identity markers. It’s wrong to rig a set of rules because you believe certain groups have too much power.

Maria Popova, a Bulgarian-born essayist, writes, “[W]hen we point the privilege finger, where do we draw the line anyway? The concept itself is so abstract and nebulous.” She points to the life of Maria Mitchell, a pioneering astronomer. Mitchell was one of nine children in a poor Quaker family and was born before most women had access to formal education. But her father educated her and introduced her to astronomy when she was young. Popova asks: “What part is the poverty and what is the privilege, and does either warrant that we dismiss Mitchell’s monumental contributions to science and culture?”

Source: PLF

A person’s power comes from what he knows and what he does. Any system based on group identity—that’s weighted to favor one group or the other—ignores the dynamism and complexity of human beings.

When Hung was a child, his parents taught him that his skill and knowledge mattered more than his background or status. “Basically, they explained to us: ‘They can take away your money. They can take away your position in life. But they can never take away the knowledge in your head,’” he remembers.

A person’s power comes from what he knows and what he does. Any system based on group identity—that’s weighted to favor one group or the other—ignores the dynamism and complexity of human beings. It also sets up barriers that prevent people from excelling as high as their skill should take them—holding the world back.

“My specialized skills, undaunted spirit and unbreakable will enable me to succeed in an environment where there are no second chances. Excellence is my standard.”

From the Navy Diver Ethos

IN THE CASE of Thomas Jefferson High School, the government assumes Asian American students’ success is evidence of their privilege. In the case of the Small Business Administration, the government assumes all black and Hispanic applicants face greater disadvantages than Marty.

Hung points out that college prep services are encouraging Asian students to hide their ambitions. “There’s people that say, ‘Hey, don’t talk about wanting to be an engineer or scientist, because right away it makes you look like you’re Asian.’ It’s ridiculous.”

Hung loves math because the rules of math are the same for everybody. “Math doesn’t lie,” he says. “I mean, I’m 52 years old right now and I can challenge anybody to do differential equations or derivatives all day long.”

To judge people as advantaged or disadvantaged and tilt the playing field accordingly doesn’t make sense, given the reality of individual experience. Even within the government’s flawed racial classifications, there’s no uniformity. Asian Americans are a “vast diverse group … often lumped together under the ‘model minority myth,’” Axios notes. The truth is that 30 percent of Southeast Asian immigrants don’t have high school degrees. How can a school board decide that Asians, as a group, have too much power?

Maria Popova writes,

To deny a person’s merit or talent or voice on account of the circumstances with which he or she was blessed or cursed—without any say in the matter—is not only to victimize ourselves as individuals but to cheat ourselves, as a culture, of the essential gift of the human spirit.

Pacific Legal Foundation represented Thomas Jefferson High School parents and alumni in a lawsuit against the Fairfax County School Board. (Read more about the TJ case on page 25.) We also represented Marty Hierholzer in a lawsuit against the Small Business Administration.

Underwater or on land, a person’s capability is what matters—not the government’s assumptions about which groups do and do not have an advantage. ♦

“Hooyah, Navy Diver!”

From the Navy Diver Ethos

A Homebuilder in California and a Landlord in Seattle

Brian T. Hodges

senior attorney

IN JANUARY, the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine’s chief diversity officer sent an email announcing the “Diversity Word of the Month”—privilege.

“Privilege is a set of unearned benefits given to people who are in a specific social group,” the email read. It continued:

People in dominant groups often believe they have earned the privileges they enjoy or that everyone could have access to these privileges if only they worked to earn them. In fact, privileges are unearned and are granted to people in the dominant groups whether they want those privileges or not, and regardless of their stated intent.

The email included a list of privileged groups, including “middle- or owning-class people.”

“So now it’s bad to save up and buy a home?” journalist Paul D. Thacker asked on X, the platform formerly called Twitter.

What was once a near-universal aspiration—to own property—is now seen as an unearned privilege. To some, the great dividing line in America is between those who own property and those who don’t. On social media, land-owning farmers are compared to “land barons.” Rental property owners are called “parasitical scum.” When Rhode Island passed a bill extending public beach areas onto private land, Redditors celebrated. “Yet again, a big loss for rich folk is a huge win for everyone,” one commented.

George Sheetz at the Supreme Court

GEORGE SHEETZ IS A PROPERTY OWNER. He’s one of many homeowners and landowners Pacific Legal Foundation currently represents in lawsuits across the country defending property rights. It’s a group of people as diverse as America itself: rich and poor, young and old, black and white, conservative and liberal.

George, whose case was argued at the Supreme Court on January 9, is a quintessential working man. He spent 50 years in construction, first as a $5-an-hour laborer and then as an engineer. “The average, everyday working person is busting their a– to try to survive and try to figure out a way to retire comfortably,” George told Fox News.

What was once a near-universal aspiration—to own property—is now seen as an unearned privilege.

His retirement plan was to build a modest, manufactured home on his plot of land in El Dorado County, California, home of the 1849 Gold Rush. But the County said George could have a building permit only if he paid a $23,420 traffic impact fee—a fee that was designed to shift the costs of commercial development and other uses onto new homes.

“I said, ‘This is ridiculous,’” George told Fox.

When he complained about the exorbitant fee at the county office, County officials told him, “You don’t have to build. No one’s making you build.”

The government was treating George’s modest ambition—to build a home on his own property where he, his wife, and grandson would live—like a luxury that vaulted him into a different status, deserving of extra burdens.

Source: PLF

George sued and spent seven years battling the County through the court system. George’s attorney is Paul Beard, a former PLF attorney now in private practice in California. When the Supreme Court agreed to hear George’s case, Paul asked PLF to join as co-counsel.

At Supreme Court oral arguments, the County’s attorney said it charged the fee to all developers according to a “premeditated schedule.” Even though George’s building plans were small in scope, the County resisted the idea of doing an individualized assessment before issuing fees.

A homebuilder is just a checkbook, to the government.

Property Owners

THE PROPERTY OWNERS PLF has represented recently include a young real estate professional in Washington State, a motorcycle-riding blacksmith in the Montana mountains, a doctor building a family retreat in Tennessee, a yoga-teaching rental property owner in California, a family of third-generation farmers in South Dakota, and a Nebraska widower trying to hold on to his only asset.

There is no shared privilege among them—no marker in all their stories that gives them a uniform level of power. What they have in common, actually, is a simple desire to assert control over their own lives—not over other people’s lives or other people’s land. Only their own.

But for those accustomed to seeing the world in black and white dichotomies, property owners represent the entrenched elite—and their property interest is seen as directly opposed to the public good. Last year, The Nation published “The Case Against Homeownership,” which argued for alternatives to private property like “social housing.”

“Through these efforts and others like them, we can help establish security for all—rather than private property for some—in a new American social pact,” author Jane Chung wrote.

The housing crisis has hardened attitudes toward property owners. The lack of housing supply in overregulated metro areas contributes to the idea that property ownership is a privilege of the upper class, which, in turn, makes it easier for the government to be cavalier about placing heavy burdens on property owners.

There’s cosmic irony there: The more burdens the government puts on property owners, the more it constrains and discourages new building, worsening the housing crisis.

Kelly Lyles in Seattle

KELLY LYLES is another property owner—and she’s about as different from George Sheetz as one could imagine.

An artist in Seattle, Kelly lives in a condo while renting out the small home she owns to two tenants. Kelly’s art is bold, colorful, and distinctly original. She relies on the monthly rent she receives from tenants to make ends meet.

Because she is a single woman in a city, and because she’s a survivor of a violent crime, Kelly is highly selective about her tenants. She needs tenants she can trust, not only to pay rent but also to be peaceable around her and to each other.

But Seattle’s Fair Chance Housing Ordinance prevents property owners from considering prospective tenants’ criminal histories when deciding who can occupy their property.

Originally, the ordinance forbade landlords from even asking about criminal histories. But Kelly and other property owners, represented by PLF, sued the City of Seattle. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled partially in the property owners’ favor: Preventing housing providers from asking about potential tenants’ criminal histories violated the First Amendment, the court said. But PLF also argued Kelly and the other owners had a right to exclude dangerous tenants from their property—and on that, the Ninth Circuit disagreed. Effectively, Seattle housing providers can now ask prospective tenants about their criminal histories, but they can’t do anything with that information, even when a background check reveals a rap sheet as long as your arm.

The City exempts itself from its own ordinance: Public housing is allowed to exclude tenants based on criminal records. It’s only private property owners who are expected to bear the risks of indiscriminately housing former criminals who may pose a threat to the property owners’ own families, other tenants, and their property.

Effectively, Seattle housing providers can now ask prospective tenants about their criminal histories, but they can’t do anything with that information, even when a background check reveals a rap sheet as long as your arm.

Source: Getty

As in George Sheetz’s case, owning property seems to put people into a separate class the government feels free to encroach on.

PLF asked the Supreme Court to consider Kelly’s case. In our petition we argued the right to exclude potential dangers is fundamental to property ownership and protected by the Due Process Clause.

“The Ninth Circuit’s conclusion that government may deprive an owner of his or her right to exclude for any conceivably legitimate public purpose is contrary to the Framers’ understanding of, and reverence for, the most essential element of property rights,” PLF wrote. Seattle’s ordinance “improperly shifts the burden of solving quintessential public problems onto individual property owners.”

In January, unfortunately, the Supreme Court denied our petition. But the fight to protect Kelly and other owners will continue when the case returns to the district court. PLF will argue that the unconstitutional ban on asking tenants about their criminal histories was so central to the ordinance that the entire thing should now be stricken.

The Fundamental Right to Property

PIERRE-JOSEPH PROUDHON was a 19th-century French socialist who argued that all property ownership was theft. In his 1840 book What Is Property?, he called landowners “thieves” for requiring rent from their tenants. Property ownership “originates in violence” and “violates equality by the rights of exclusion,” Proudhon wrote. “[P]roperty and robbery are synonymous terms… All men in their hearts, I say, bear witness to these truths; they need only to be made to understand it.”

That idea—that owning property is somehow an infringement of other people’s freedom—still exists, even in the United States.

But here, at least, property owners have history on their side: America’s Founders considered the right to property so fundamental that the British practice of “quartering”—housing troops in private homes—was among the Founders’ chief complaints in the Declaration of Independence. With quartering, too, the government expected property owners to bear certain public burdens, and American property owners said no. The Founders also baked property rights into the Constitution, particularly in the Fifth Amendment. (“No person shall… be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.”)

The more today’s property owners fight back against unjust encroachment and restrictions of their property, the easier it will become for more people to build, own, and make productive use of property in America. That’s better for each individual property owner who may, through those efforts, more readily reap the rewards of hard work—and it also undermines the cynical argument that positions property owners as a separate class oppressing everyone else. ♦

Two Women Fight Set-Asides and Quotas

Laura D’Agostino

attorney

DR. AZADEH KHATIBI grew up in Tehran in the early 1980s. Her father wanted sons; he got two daughters. “He was like, ‘What is their future going to be like?’” she says. Iran’s new theocratic government oppressed women in every way, from clothing to schooling.

This was after the Islamic Revolution of 1979. The country’s constitution, written in 1906, had been thrown out; Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini became Supreme Leader. Women, who had freely worn dresses and socialized with men during the seventies, were suddenly forced to wear the hijab and banned from men’s spaces.

“At that point,” Dr. Khatibi remembers, “they’d closed the universities down for three years to revise the textbooks and make sure people were learning what was deemed ‘correct’ to learn. A lot of people’s lives got twisted in a really bad way.”

So the family left. Dr. Khatibi’s father wanted more for her than Iran would allow. They moved to Southern California, where women would not be treated as a separate class of citizens.

‘The Great Lawsuit’

“HER FATHER WAS A MAN who cherished no sentimental reverence for woman, but a firm belief in the equality of the sexes… He addressed her not as a plaything but as a living mind.” That wasn’t written about Dr. Khatibi’s father, although perhaps it could have been. It’s from American journalist Margaret Fuller’s 1845 book Woman in the Nineteenth Century, about a character she based on herself. Fuller originally published the book as a serialized essay with a far-more-interesting title: “The Great Lawsuit: Man versus Men. Woman versus Women.”

“[M]an cannot, by right, lay even well-meant restrictions on woman,” Fuller wrote. What she asked for was simple: “We would have every arbitrary barrier thrown down,” she wrote. “We would have every path laid open to woman as freely as to man.”

In 1845 Fuller argued women could fill any off ice. “Let them be sea-captains, if you will,” she quipped. Today in America there is no field open to men that is not legally open to women.

For Fuller, each woman was an individual first and foremost. A woman’s femininity was a characteristic, not the essential whole of her. “What woman needs is not as a woman to act or rule, but as a nature to grow, as an intellect to discern, as a soul to live freely and unimpeded, to unfold such powers as were given her when we left our common home,” she wrote.

The only remedy to unequal freedom, she said, “must come from individual character.”

The vision Margaret Fuller laid out in 1845 is what draws immigrant families like the Khatibis to America. In the 179 years since Fuller’s book was published, America has rid itself of “every arbitrary barrier” legally preventing women from participating in government, industry, property-ownership, and art. In 1845 Fuller argued women could fill any office. “Let them be sea-captains, if you will,” she quipped. Today in America there is no field open to men that is not legally open to women. There are female captains at sea and female pilots in the sky.

To paraphrase Chief Justice John Roberts, the way to stop discrimination is to stop discriminating. Implicit bias training encourages doctors to be ever-conscious of identity-based groups, which can undermine the goal of equal treatment for all.

But the oppressor-oppressed worldview still positions all women below men, regardless of individual circumstances, and maintains that women are an oppressed class that needs legal quotas, mandates, and set-asides to be truly empowered.

It’s a worldview belied by the success of women like Dr. Azadeh Khatibi, now a California ophthalmologist who is fighting mandatory “implicit bias” trainings in medical education.

Implicit Bias

“AZADEH” MEANS FREEDOM. It’s a fitting name for Dr. Khatibi.

Growing up in Southern California, she loved acting. She thought about studying to become an actress but wanted to feel like she was making a difference. “I thought, ‘I have to go to work every day and help someone,’” she says.

She also wanted security. Her early years in Iran affected her. “I grew up in this milieu of people in a constant state of shock and trauma and insecurity and worry,” she reflects.

She studied ophthalmology at the University of California, Berkeley and did her residency at UC Irvine while raising two kids. She didn’t give up entirely on her Hollywood dreams: She produced several films over the past ten years, including the animated film Window Horses starring Sandra Oh.

Source: National Portrait Gallery

Dr. Khatibi also taught continuing medical education (CME) courses, which doctors must take periodically to keep their licenses. But in 2019, California passed a new law requiring all CME courses to include implicit bias training.

Implicit bias training is designed to make people aware of how they might be stereotyping others based on sex, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or other characteristics. For doctors, the goal of implicit bias training is to prevent the unequal treatment of patients.

But there are a couple of problems: One, the jury’s out on whether implicit bias trainings have a positive impact, as Scientific American and MSNBC report. In fact, “[i]mplicit bias training can actually reinforce harmful stereotypes,” MSNBC notes. To paraphrase Chief Justice John Roberts, the way to stop discrimination is to stop discriminating. Implicit bias training encourages doctors to be ever-conscious of identity-based groups, which can undermine the goal of equal treatment for all.

The second problem is the state is forcing CME teachers like Dr. Khatibi to spend limited course-time on implicit bias training instead of allowing them to decide for themselves what’s relevant for doctors.

“You’re actually changing the narrative of medicine,” Dr. Khatibi says. “You are being forced by law to teach something else.” It reminded her of Iran. “When you grow up in a theocracy that’s very repressive, people are constantly worried about someone reporting them or doing the wrong thing,” she says. “It really messes up your psyche as an individual.”

There’s an awful irony in what California is doing: To help groups it believes are oppressed, including women and immigrants, the state is forcing an Iranian-born woman to teach bias trainings against her will.

There’s an awful irony in what California is doing: To help groups it believes are oppressed, including women and immigrants, the state is forcing an Iranian-born woman to teach bias trainings against her will.

Source: Dr. Khatibi

Dr. Khatibi is represented by PLF in a lawsuit challenging the mandatory trainings.

Set-Asides and Quotas

THE GOVERNMENT’S TOP-DOWN MEDDLING can be frustrating for women who worked hard to rise in their industry.

Debbie Ferrari is, like Dr. Khatibi, a successful California professional. She spent almost 40 years moving up the ranks in the construction industry. She started in bookkeeping at a trucking company before moving to operations; now she’s a manager at the company.

Since the 1980s, California has set aside some public works contracts for minority- and women-owned businesses. The state’s “Construction Compliance Program” sets a goal of 15 percent minority-owned businesses and five percent women-owned businesses.

Ms. Ferrari works at a diverse company: They have truckers and staffers from Mexico, India, and Vietnam. “We’ve got a lot of women in our office,” Ms. Ferrari adds.

But the company isn’t certified as minority- or woman-owned, so it can’t win certain public jobs. The sex and race of the company’s owners now “trump price and the ability to perform,” Ms. Ferrari says. The individual staffers at the company—including women like Ms. Ferrari—are being robbed of opportunities because of California’s artificial barriers.

Ms. Ferrari and the Californians for Equal Rights Foundation are represented by Pacific Legal Foundation in a lawsuit challenging the discriminatory set-asides.

A Victory in Iowa

IN JANUARY, PLF WON A VICTORY for equality in a separate lawsuit in Iowa: A federal judge ruled for PLF client Charles Hurley and struck down a gender quota for the State Judicial Nominating Commission. Iowa argued that the quota was “appropriately enacted to address the absolute absence of women” on the commission and that it remedied past discrimination. “Even if it would be appropriate to end the gender-balance requirement someday, today is not that day,” Iowa said.

Source: National Archives

The government bore the burden of showing its sex-based classifications passed strict intermediate scrutiny, and it failed that burden.

But today is that day. In its decision, the court said it “cannot find the law is substantially related to any current discrimination.” The government bore the burden of showing its sex-based classifications passed strict intermediate scrutiny, and it failed that burden. The court ruled that Iowa’s quota violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution.

It was a strike in the right direction—toward a government unfettered by identity-based obstacles.

The Future for Women

FOR A LONG TIME after the Founding, the American legal system failed women. Women could not participate in the political process. Married women couldn’t hold property in their own names.

The Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868, guaranteeing all citizens “the equal protection of the laws.” Myra Bradwell, publisher of the Chicago Legal News, sued the State of Illinois the following year; she had passed the Illinois Bar exam but was denied a license because she was a married woman. Her case went before the Supreme Court in 1873.

She lost, 8 votes to 1. “The paramount destiny and mission of woman are to fulfill the noble and benign offices of wife and mother,” Justice Joseph Bradley wrote in a concurrence.

That history of legal oppression is a hard yoke to forget. But it should not determine how the law treats people in 2024. Obstacles of the past don’t justify obstacles now: What was right then is also right today.

American women are hardly a homogenous class. Even Dr. Khatibi and Ms. Ferrari, two successful California women with similar views, have vastly different experiences. Does it make sense to have a quota or mandate that lumps these two women, and all women, together as a group that needs government help?

The persistent worldview that all women in America are oppressed by male oppressors can, at times, venture into the absurd.

For instance: Last year country singer Luke Combs covered Tracy Chapman’s classic 1988 single, “Fast Car.” After Combs’ version hit No. 1 on the Billboard Country chart, The Washington Post published an article about how problematic the cover’s success was. Chapman, the Post argued, “as a black queer woman,” would “have zero chance” of having the same success as Combs, a white man.

Readers quickly disagreed, pointing out that Chapman’s original version was a big hit when released and that she was now earning royalties from Combs’ country version. The takeaway should be that art can be universal, one Twitter user argued. “That a black lesbian and a straight white man may feel the same depth and story despite identity differences. What if we pushed that narrative.”

Even Dr. Khatibi and Ms. Ferrari, two successful California women with similar views, have vastly different experiences. Does it make sense to have a quota or mandate that lumps these two women, and all women, together as a group that needs government help?

In the leadup to the 2024 Grammys Awards in February, promos teased a performance by Luke Combs. But in a surprise at the ceremony, Tracy Chapman joined Combs for a moving duet of “Fast Car.”

“I had a feeling that I belonged,” the two sang together. “I had a feeling I could be someone.”

Afterwards, as the crowd cheered, Combs turned and bowed deeply to Chapman. He seemed visibly awed by her. It was a lovely moment between two successful stars—and no one watching could possibly come away thinking that Combs, by virtue of being a man, was the one with greater power. ♦

Power and Privilege in America’s Schools

Erin Wilcox

attorney

YIATIN CHU’S 26-YEAR-OLD daughter isn’t thrilled her mother is suing the New York State Department of Education.

In January, with Pacific Legal Foundation’s help, Yiatin and several others filed a lawsuit challenging New York’s Science and Technology Entry Program (STEP), which hosts test-prep, training, and instruction for 7th-to-12th-grade students. Yiatin’s problem with the program? It’s not open to all New York students. Kids are eligible only if they’re economically disadvantaged or identify as black, Hispanic, Native American, or Alaska Native.

In other words, the child of black millionaires is eligible for STEP, but the child of Chinese or Ukranian immigrants living just above the poverty line is not.

Yiatin believes in a colorblind, meritocratic education system. She has two daughters; her younger daughter is in seventh grade and would be eligible for STEP if she identified as one of the underrepresented minorities.

But Yiatin’s older daughter, an adult, argued with her mother about the lawsuit.

“She said, ‘Mom, come on. Meritocracy is a myth,’” Yiatin recalls. The world is about connections and who you know, her daughter told her.

Yiatin was born in Taiwan. Back there, her dad was an engineer and her mother was a schoolteacher. They immigrated to America to escape the instability of that part of the world, for their children’s sake. In New York City, her dad found work in a factory running machines. Her mother took a job as a filing clerk. They taught themselves English and sent their kids through the public school system, where Yiatin excelled and ended up testing into one of the city’s Specialized High Schools for gifted kids. She later worked at several startups and tech companies, including WebMD.

Yiatin believes in a colorblind, meritocratic education system. She has two daughters; her younger daughter is in seventh grade and would be eligible for STEP if she identified as one of the underrepresented minorities.

Now Yiatin argued with her daughter, pointing out that her own life was a story about meritocracy. “Your grandparents, my parents, we didn’t have any connections,” Yiatin reminded her daughter. “I didn’t inherit anything. I did everything on my own.”

“But you’re unusual,” Yiatin’s daughter countered.

“Just because it’s not common doesn’t mean it’s not a value you aspire to,” Yiatin replied.

The Coalition for TJ

YIATIN’S LAWSUIT IS JUST BEGINNING. Two hundred and fifty miles south, another PLF lawsuit is coming to a disappointing end.

In February, the U.S. Supreme Court turned down the Coalition for TJ’s case challenging the new admissions process at Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology in Virginia. PLF had litigated the case for three years. Unlike most petition denials, this one did not come quickly: The Court considered taking the case over five separate conferences before ultimately rejecting it—and Justice Samuel Alito wrote a strong dissent, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas.

For the members of the Coalition for TJ—many of them Asian American parents and alumni—and their Pacific Legal Foundation attorneys, the answer is clear: Rigging admissions to increase enrollment of certain races while decreasing others is unconstitutional, no matter how politely a school does it.

Allowing the Fairfax County School Board’s admissions process to continue “effectively licenses official actors to discriminate against any racial group with impunity as long as that group continues to perform at a higher rate than other groups,” Justice Alito wrote. “That is indefensible.” He called the reasoning behind the school board’s victory “a virus that may spread if not promptly eliminated.”

In February, the U.S. Supreme Court turned down the Coalition for TJ’s case challenging the new admissions process at Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology in Virginia. PLF had litigated the case for three years. Unlike most petition denials, this one did not come quickly: The Court considered taking the case over five separate conferences before ultimately rejecting it—and Justice Samuel Alito wrote a strong dissent, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas.

TJ’s new process was developed in 2020 to change the racial makeup of the school “towards greater equity, to be clearly distinguished from equality,” as one school board member put it. Unlike STEP in New York, TJ does not explicitly use race as a determining factor in admissions. Instead, it replaces the old colorblind entrance exam with a points system that awards students for certain “Experience Factors,” including attending an underrepresented middle school.

That’s what makes it a high-profile case. After the Supreme Court ruled against affirmative action in the Students for Fair Admissions cases last year, the question became: Could schools still skew their admissions policies to favor certain groups, as long as they did it cleverly and covertly? Or is it wrong for the government to distribute benefits and burdens on the basis of race, even if it couches the process in neutral words?

For the members of the Coalition for TJ—many of them Asian American parents and alumni—and their Pacific Legal Foundation attorneys, the answer is clear: Rigging admissions to increase enrollment of certain races while decreasing others is unconstitutional, no matter how politely a school does it. As Chief Justice John Roberts said in the Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard/UNC decision, quoting an 1867 Supreme Court decision, “[W]hat cannot be done directly cannot be done indirectly. The Constitution deals with substance, not shadows.”

But opponents of the TJ lawsuit pushed back. Sonja Starr, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School, called TJ a “dangerous” lawsuit and says the idea that our Constitution is colorblind shouldn’t apply to “benign classifications benefiting people of color[.]”

And Janel George, a professor at Georgetown Law, said the Coalition for TJ’s “opposition to diversity efforts perpetuates a myth of meritocracy rooted in white supremacy”—a strange thing to say about a majority-Asian, predominantly immigrant group.

Breaking the Narrative

IF YOU BELIEVE American school systems are systemically biased against minorities and designed to keep power among entrenched groups, Asian Americans don’t fit neatly into your worldview.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, about six percent of the U.S. population identifies as Asian American. It’s half the size of the population that identifies as black and about a third of the population that identifies as Hispanic. But at many top public high schools—including Stuyvesant in New York City and TJ in Virginia—Asian American students have become a majority. Many, like Yiatin, are immigrants or first-generation Americans. They rose to the top of their classes and successfully applied to magnet schools through colorblind processes.

For their success, these Asian American students are derided as privileged and “white adjacent.” At a 2022 DEI training, a San Diego school superintendent said Chinese American students do well in school because their parents are wealthy—a sweeping generalization that positions an entire group of people as oppressors and downplays students’ individual successes.

The truth is Asian Americans are a diverse group. In 2019, New York Times Magazine writer Jay Caspian Kang sat down with several Asian American students to discuss their feelings about affirmative action. Kang is also Asian American. When he met with an 18-year-old named Alex, Kang found him “somewhat annoying at first.”

Source: PLF

“I saw in Alex the stereotype of the Asian grade-grubbing machine,” Kang wrote.

But Kang quickly realized he himself was guilty of “a certain arrogance and presumption—that because you look like your subject, your perspective carries some revelatory power[.]” He and Alex were both Asian but had lived different lives. Kang grew up in a majority-white neighborhood in Cambridge, Massachusetts, while his father earned a post-doctorate in organic chemistry at Harvard. Alex was from Flushing, Queens, where his father, Qiao, worked as a technician. Qiao had grown up in poverty in rural China. Life hadn’t been easy for him as an immigrant, Qiao told Kang. But he vastly preferred America to the corruption of China.

“Everything was open in America,” Qiao told Kang. “If I had the right paperwork for something or if I finished the work I was supposed to do, the right thing would get done. At least I could trust that.”

Alex, Qiao’s son, was gifted: He got into Bronx Science, one of New York’s Specialized High Schools.

Kang asked Alex how he felt about affirmative action. “I understand the thinking behind affirmative action,” Alex said, “but I just wish the message wasn’t that Asians are all so privileged and rich and buying their way into colleges. And I wish that it didn’t mean that my work didn’t count in the same way as other people’s work.”

A Teacher Fights for Meritocracy

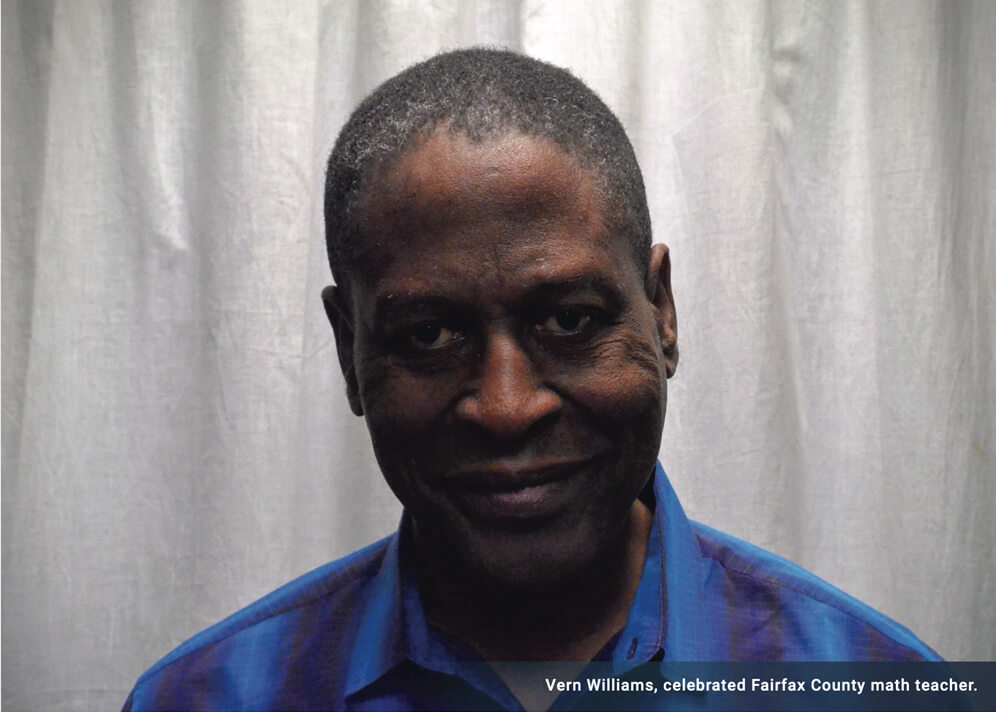

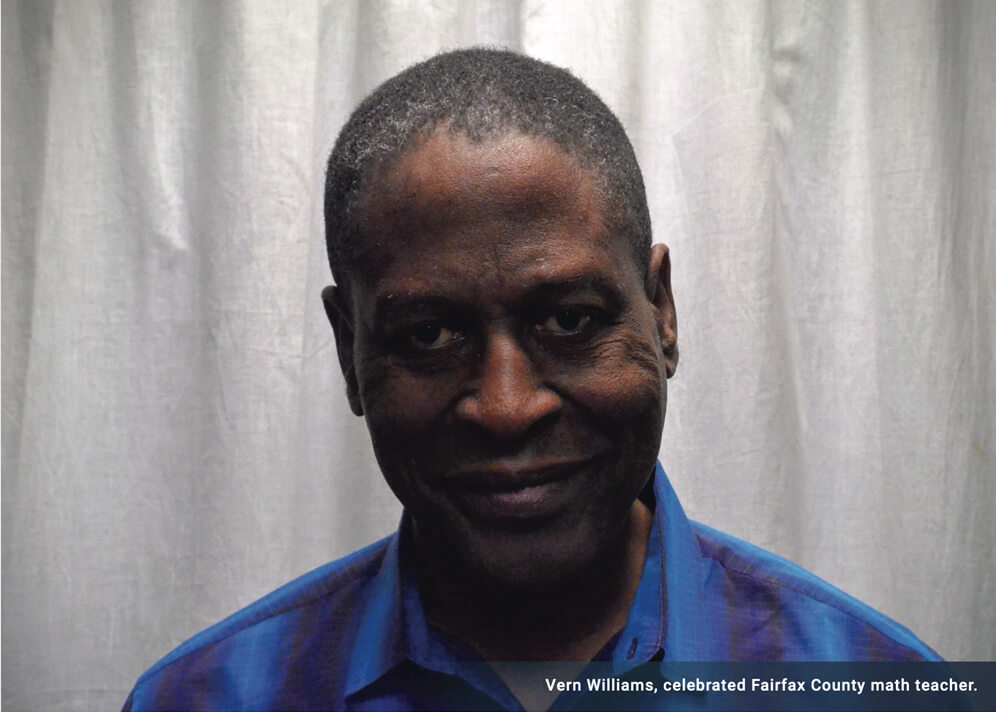

VERN WILLIAMS is a member of the Coalition for TJ. He’s neither Asian nor an immigrant: Vern is black and grew up in segregated DC. At school he fell in love with math; he became a teacher and taught middle school math in Fairfax County for 40 years. “By all accounts, he is one of the best math teachers in the country,” The Washington Post wrote in 2011.

Source: Vern Williams

He worked with students in Fairfax County’s gifted and talented program. “It used to be called the gifted and talented center,” Vern says. “I remember the year they got rid of that. They said, ‘No, we can’t do that. Because that’s implying some kids are born with a gift.’”

If you’re an exceptional math student in Fairfax County, TJ is where you want to go to high school. Vern prepared countless students for the TJ application process and wrote recommendations. “Some of these kids are beyond brilliant,” he says. “Their mind is so studded with brilliance that they probably don’t have room for their address.”

But even before the Fairfax County School Board changed TJ’s admissions process, Vern saw a shift happen at the school—away from an emphasis on individual excellence toward an insistence on group equity. He told The Washington Post that in 2004, the recommendation form for applicants asked teachers to rate students on their interest in math, self-discipline, and problem-solving skills. But by 2011, the recommendation form was asking teachers to rate on intellectual ability, commitment to STEM, and how the student would “contribute to the diversity of [TJ’s] community of learners.”

“It used to be called the gifted and talented center,” Vern says. “I remember the year they got rid of that. They said, ‘No, we can’t do that. Because that’s implying some kids are born with a gift.’”

When Vern complained to the Post about the initial changes to the recommendation process, a reader wrote a letter to the editor in response:

Cheer up, Mr. Williams… Faced with a similar task some years ago, a colleague removed any hesitation I might have felt doing it by suggesting my letter of recommendation include the following statement: “This student belongs to a very small minority. He has mathematical talent.”

Today, under the new admissions process, there are no teacher recommendations at all.

The Strongest Voices

TO VERN WILLIAMS IN VIRGINIA and Yiatin Chu in New York, and to other teachers, parents, and students across the country, school should be an arena for the pursuit of individual excellence. But to those who see the world through an oppressor-oppressed framework, people are not defined by their own talents and ambitions but by their status in relation to others. A person’s success isn’t just success in this worldview; it’s a form of oppression because it leads to unequal outcomes.

That’s a particularly awful worldview to bring to schools, where students should be excited by their individual potential to be different, to rise above.

Immigrants and first-generation Americans are among the strongest voices opposing the oppressor-oppressed framework, because it contravenes the reason their families came to America: where the laws are meant to be open and the people equally free.

The strongest voices against it also tend to be parents. When Yiatin sees young activists and teachers promoting race-based enrollment, she thinks: You know what? Wait until they have kids.

“There are certain times in our lives where our values will start shifting,” she says. “And when you become a parent, you see the world through a different lens.” ♦

Secure Freedom for Future Generations

Thanks to you, for the past half-century, PLF has been there for everyday citizens who had nowhere else to turn when threatened by overreaching government. Indeed, you’ve helped build PLF into what we are today: a force to be reckoned with.

But what about tomorrow? Where will people go years from now when their rights are crushed by government’s excessive quest for control?

As a Legacy Partner, you will secure PLF’s lasting leadership in defending liberty so succeeding generations will know, cherish, and live the promises of our Constitution.

Will you join us in the long fight for years to come?

We invite you to join our Legacy Partners, a group of dedicated supporters, who have added PLF to their will, trust, or other estate plans.

For assistance, contact Jim Katzinski, Gift Planning Officer, at (916) 288-1395 or return the enclosed envelope noting your interest in estate planning.

555 Capitol Mall, Suite 1290

Sacramento, CA 95814