Spring 2023

To read more about the work that PLF is doing, visit pacificlegal.org.

Fifty years. This month, 50 years ago, Pacific Legal Foundation was officially incorporated in California. In preparation for the anniversary of this momentous occasion and our upcoming celebration in Washington, DC, later this month, I took the opportunity to dive into our archives and look at just how our founders brought PLF into being—and the pioneering spirit and bravery it required to pull it off.

The idea of PLF was new. There didn’t yet exist a public interest law firm dedicated to vindicating constitutional rights and expanding individual liberty. Up to that point, most of the so-called public interest law firms were most enthusiastic about expansive government intervention, not restricting government to its limited and enumerated powers. As you’ll read in this issue, Ron Zumbrun, the intellectual mastermind behind PLF, had other ideas. It could’ve been easy for Ron and other early PLF staffers to remain in their more secure jobs in California Governor Ronald Reagan’s administration. Instead, they struck out on their own, into uncharted territory, to build an organization consistent with the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. That swashbuckling attitude has made America much freer as a result.

But successful public interest law can’t happen without brave pioneers of another sort: our clients. We’ve represented thousands of people over our five-decade history, and each one of them has a unique story. Yet there’s something that connects them, something they all share—a willingness to stand up against significant odds, social and political pressure, and potential financial ruin. Our clients know—and relish—that they aren’t just fighting for themselves. They are fighting for all of us, confronting government violations of individual rights head on, in the most personal way possible, and taking the law to a place it’s never been before. Whether at the Supreme Court or a local tribunal, every victory means there’s a little bit more liberty in this country. You’ll get to know some of them a little better and learn how they stood in the face of giants in the articles that follow.

In the years PLF’s been around, scores of other organizations have popped up, engaging a similar theory of social change—and that’s good because we need all of them, not only to file lawsuits where government overreaches, but also to challenge us to grow and innovate as an organization. It’s not 1973 anymore; jurisprudence evolves, and so must we.

That’s what makes this work so profoundly exciting. We’ve no doubt found great success since our founding—some of which I’ve been able to share with you personally—but we know that our greatest successes remain to be achieved. It just can’t be any other way. The future of our principles, our families, and our nation depend on it. Here’s to celebrating this month’s milestone with the knowledge we’ll be celebrating ever more in the years to come. Cheers.

Steven D. Anderson

PRESIDENT & CEO

The Mountain Man v. The Forest Service

Jim Manley

Attorney

Mountain lions are solitary animals. They don’t move in packs; they prefer to be left alone. A mountain lion will stick to his territory. He’ll generally avoid human beings.

But sometimes, hunters go looking for mountain lions.

Here’s how a mountain lion hunt works in Montana: Tourists pay thousands of dollars to guides, who wait until a fresh snow blankets the ground. That makes the lion’s prints easy to track. Once the guides find a lion’s trail, they let loose a pack of hounds that chase the lion up a tree, pinning him in place.

At that point, the hunt is child’s play: A tourist can stand under the tree and easily shoot down the trapped mountain lion, like shooting fish in a barrel.

“I don’t agree with it,” says Wil Wilkins, a 73-year-old blacksmith who lives on the outskirts of Montana’s Bitterroot National Forest. He has seen these hunts, because they sometimes take place on his private property. Hunters have been trespassing ever since the U.S. Forest Service invited the public to use a private road that cuts across Wil’s land.

Hunters have been trespassing ever since the U.S. Forest Service invited the public to use a private road that cuts across Wil’s land.

Having tourists trek across his land to hunt a mountain lion sickens Wil. The tourist’s goal is to take a photo with the dead animal. And the mountain lion has no chance at all once he’s up a tree, surrounded by hunters and hounds.

It’s not hard to understand why Wil sympathizes with the mountain lion. The mountains are his home, too. Like the lion, he wants to be left alone.

And he too is being forced to play a rigged game.

A Private Road

When Wil went to the U.S. Forest Service office to ask what was going on with Robbins Gulch Road, the district ranger laughed at him.

Wil wanted to know why the Forest Service had posted a “public access” sign on Robbins Gulch, the private road that cuts through his property and the property of his neighbor, Jane Stanton, an elderly widow.

Prior landowners granted the Forest Service an easement in 1962, allowing the agency to use the road for timber harvesting. But in 2006, someone from the Forest Service put up the public access sign. Out-of-state strangers began zooming through Robbins Gulch Road. One speeding driver ran over two of the neighbor’s dogs, killing one and crippling the other. Hunters came onto Wil’s land and fired shots near his house. Someone even shot Wil’s cat. (The cat, like its owner, is made of stern stuff—it survived the shooting.)

The Forest Service’s response to Wil, when he first complained after the sign went up, was reassuring: They said the road would soon be decommissioned and removed from Forest Service maps.

But that’s not what happened. After about nine years of bureaucratic feet-dragging and obfuscation, the Forest Service released a plan to open up several roads for public access, including Robbins Gulch Road.

That’s when Wil went to the district ranger.

“I said, ‘Look, this is going from a decommissioned road to now, it’s a public road. And you’re encouraging use of it, of people running four-wheelers and loops through here.’”

The district ranger told Wil the Forest Service had the right to make the final decision about the road’s use.

“What if I disagree?” Wil retorted.

That’s when the district ranger laughed at him.

“Well, Wil,” the ranger said, laughing. “You could always sue us.”

An Attitude of Entitlement

In a 2017 article in The Montana Pioneer, Terry Anderson, former president of the Property and Environment Research Center, noted the U.S. Forest Service’s “arrogance.”

Anderson wasn’t writing about Wil’s dispute, but about the Hudson family, who for decades allowed the public to cut through their private property on a trail that was clearly marked “Private Property. Please Stay on the Trail.” There was no official easement; the Hudsons simply gave the Forest Service permission to use the trail as a public access path.

“Why should we have to sue the government to make them do what they promised they would do?” Wil asks, frustrated. “I mean, it just tore my guts out.”

But when the Forest Service pushed the family to grant an easement, the Hudsons asked whether the trail could be shifted slightly so that it no longer came within 15 yards of their house. The family even offered to pay to redo the path.

Instead of accepting the generous offer, the Forest Service claimed that on second thought, it didn’t need the Hudsons to grant an access agreement; the public’s continuous use of the trail already created a “prescriptive easement,” the agency said.

The Hudsons were forced to file a Quiet Title Act claim to challenge the Forest Service. Unfortunately, the family lost in court.

Anderson writes:

To see how far Forest Service officials are willing to push for access across private property, consider the advice District Ranger Alex Sienkiewicz (Yellowstone Ranger District) posted on July 7, 2016, on the Facebook page of the Public Land/Water Access Association, a group notorious for advocating public access as an entitlement. Sienkiewicz’s advice: “NEVER ask permission to access the National Forest Service through a traditional route shown on our maps EVEN if that route crosses private land. NEVER ASK PERMISSION; NEVER SIGN IN (concerns—come see me). … Whatever past DRs [district rangers] or colleagues have said, I am making it clear, DO NOT ASK permission and DO NOT ADVISE the public to ask permission.

Asking permission gave power to private property owners, which the Forest Service did not like. Simply taking was Ranger Sienkiewicz’s preferred path.

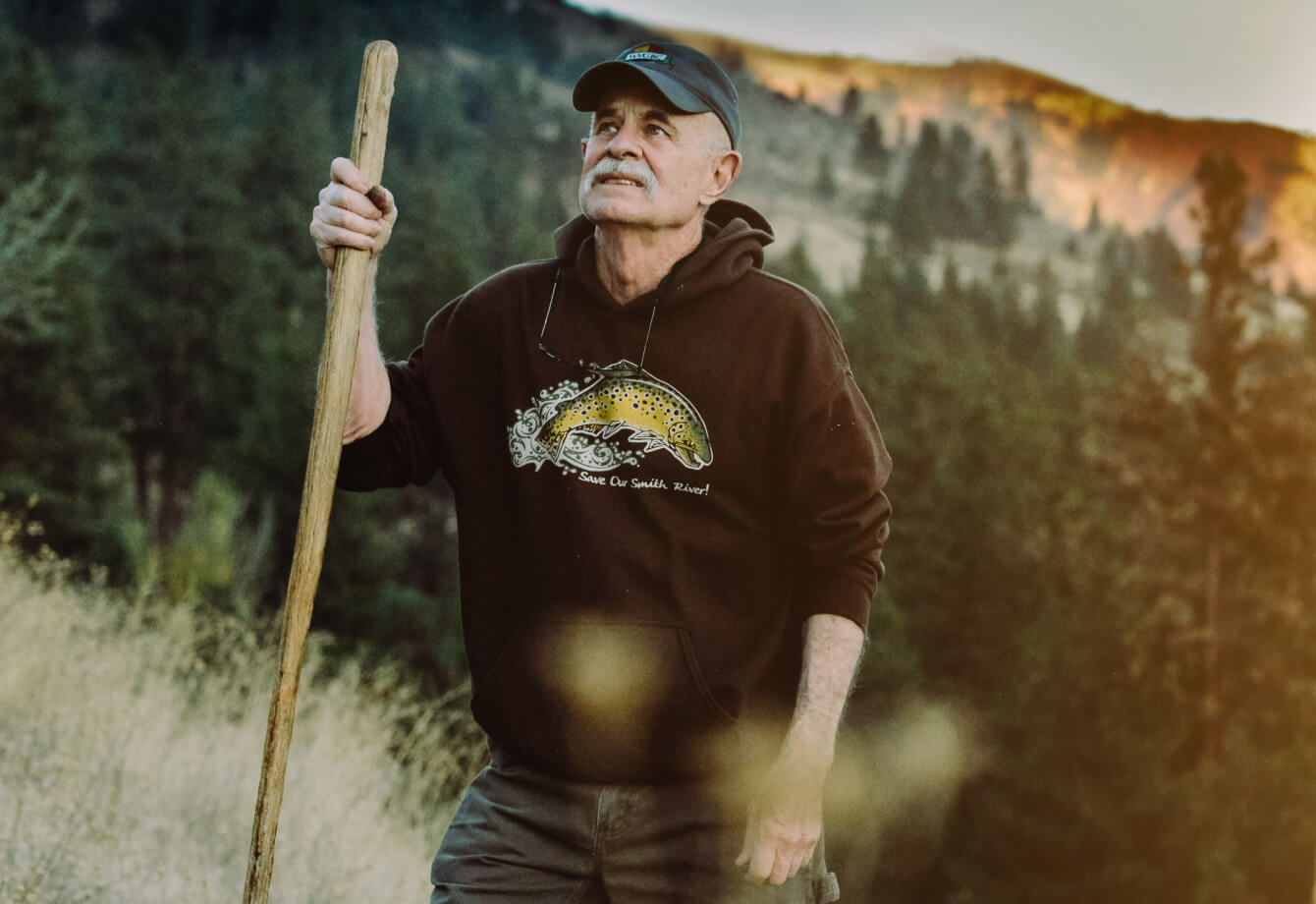

Wil Wilkins near his home in Montana’s Bitterroot National Forest.

Defending His Home

Wil’s mother used to say he was born a century too late. He was raised by his Mennonite grandparents in an Appalachian home with no television or hot water. They used an outhouse.

Today Wil is a motorcycle-riding blacksmith who performs cowboy poetry and designs stunning iron chandeliers for luxury hotels and private homes. His work has been featured in interior design magazines, even though he keeps a low profile. His business doesn’t even have a website.

If you ask Wil why he loves living in the mountains, he’ll be somewhat baffled by the question: Who wouldn’t want to live there?

“I look across and I see the mountain ridges, and then up above is a snow-cap granite mountain peak,” he says. “And if that doesn’t give people goosebumps to hear about that, I am sorry, but that’s just my ideal place to live.”

He could not accept what the Forest Service was doing to him. The plain text of the decades-old agreement clearly stated the property owners were only granting an easement for timber harvesting, not public use.

“You could show the plain text of the original agreement to a bunch of high school kids and they’d say, ‘Yeah this is not for public use,’” Wil says. But when he reminded the Forest Service of the original agreement, the agency acted as though it didn’t matter.

“Why should we have to sue the government to make them do what they promised they would do?” Wil asks, frustrated. “I mean, it just tore my guts out.”

What made him especially upset was how the Forest Service misled him when he initially complained about the public access sign. For years, he’d trusted the process to play out—a delay that would end up costing him in court.

“They held me back nine years, telling me my road was going to be decommissioned,” Wil says.

At one point, he thought about selling and moving. But he loves his home in Bitterroot Valley.

“If I sold this place for one million dollars, I couldn’t replace it,” he says. “I couldn’t have everything I have here, which is the serenity, the river right across the road from me …. I’ve been all over this country. And there’s not another place that I can think of that I would want to move to.”

He decided to fight. In 2018, he sued the Forest Service.

At the Supreme Court

In November 2022, Wil sat in the gallery of the U.S. Supreme Court while Pacific Legal Foundation attorney Jeff McCoy argued Wil’s case before the nine Justices. I was in the courtroom, too, sitting at Jeff’s table.

The government’s argument is that Wil waited too long to sue; the Forest Service claims the Quiet Title Act’s 12-year statute of limitations has lapsed, a claim Wil disputes on factual grounds. But so far, the courts have accepted the government’s procedural argument, which means Wil hasn’t been able to make his case on the merits.

“The Forest Service wants to overpower me with this legal mumbo jumbo,” Wil says, outraged. Without the chance to tell his story, he felt like everyone—even people in his own town—were jumping on the government’s side.

But the Supreme Court agreed to review the case, and Wil flew from Montana to Washington, DC, for oral argument. “I was so impressed by the Supreme Court that they would want to hear my case,” Wil says.

As he sat in the courtroom—cutting a striking figure in a leather vest and bolo tie—Wil couldn’t hear what the attorneys and Justices were saying about the case that bears his name. Wil is hearing impaired. The Supreme Court offers sound-amplifying headsets for visitors with hearing loss, but the staff didn’t offer one to Wil and he didn’t think to ask.

Instead, he focused on watching the way everyone moved and the expressions they made—almost like it was a silent play.

“All I could do was watch the body language of everyone there,” he told us afterward.

He noticed that Jeff didn’t read his opening statement off a piece of paper: He stood in front of the Justices and spoke directly to them. Wil liked that.

Wil also noticed that the Justices had more questions for the government than for Jeff. Wil saw a couple of the Justices pointing their fingers at the government’s attorney, like they were admonishing him.

But the best moment came at the end.

“When Jeff went up for his closing, every one of the Justices leaned forward with a hundred percent attention for what he was saying,” Wil says. “And when he finished, they all kinda eased back in their chairs.”

“This is not about just me,” Wil says. “This is turning out to be about millions of Americans who might face the same thing. If we win this case, it’ll be a landmark.”

Wil couldn’t hear it at the time, but here’s what Jeff was saying in that moment: He was reminding the Court that Congress passed the Quiet Title Act so that property owners could finally challenge the federal government over land disputes. Before the Quiet Title Act became law, Americans had little recourse against the government and “there were gross inequities.” Ruling against Wil on procedural grounds would make it harder for other property owners to resolve inequities.

Wil echoed that sentiment months later, as he and PLF waited—and continue to wait, as of this writing—for a decision from the Court.

“This is not about just me,” Wil says. “This is turning out to be about millions of Americans who might face the same thing. If we win this case, it’ll be a landmark.”

And if the government rules against him?

Even then, Wil says, “I won’t stop fighting.” ♦

The Grandmother v. The Theft

Christina Martin

Senior Attorney

Geraldine Tyler, the 94-year-old Minneapolis woman at the center of next month’s argument before the Supreme Court in Tyler v. Hennepin County, only owed $2,300 in property taxes. That’s what started this whole thing.

Ms. Tyler acquired a small condominium in 1999. After she moved in, crime in her neighborhood began increasing and because she was elderly and living alone, she and her family became concerned about her health and safety. In 2010, Ms. Tyler finally began renting an apartment in a safer neighborhood and the property taxes on the condominium went unpaid.

When you fall behind on property taxes, the government has a right to seize your property and sell it to settle your debt. That’s what Hennepin County did, selling Geraldine’s condo for $40,000.

The tax debt started out as only $2,300, but that ended up being only a fraction of Geraldine’s total debt to the government. The county tacked on thousands of dollars in interest, penalties, and other costs that eventually brought Geraldine’s total bill up to $15,000.

Geraldine should have gotten $25,000 from the sale after the county satisfied her $15,000 debt. But instead the government pocketed the whole $40,000.

Geraldine at 94

Geraldine is still sharp at 94 years old. She has three children and four grandchildren, whom she adores. She also has a 76-year-old niece, Joan, who orders Geraldine’s groceries and checks in on her. The two women have been close all their lives. Now they’re the oldest ones left in their family. Sometimes they attend parties at their social club; other times they call each other and talk about the past—the relatives they’ve lost, their shared memories from Joan’s childhood, and Geraldine’s stories from when she was young. (“She went out with one of the Tuskegee Airmen,” Joan says.)

When you fall behind on property taxes, the government has a right to seize your property and sell it to settle your debt.

Both women used to work for the government, incidentally. Joan worked in human resources at the Department of Homeland Security and Department of Agriculture. Geraldine worked for Hennepin County—the same county that took $25,000 of home equity from her.

Joan is surprised about what happened to her aunt. “We’re finding out that this is what the government does, this is the practice they have,” she says indignantly. “They take your stuff and then they make a profit off of it and you don’t get anything. And how many people have they done this to? And how is this fair? How can this even be a thing?”

Leaving the Condo

The one-bedroom condo Geraldine owed taxes on is in the neighborhood of Folwell in North Minneapolis. Geraldine was 70 years old when she bought the condo, and for a decade she lived there and paid property taxes every year. But as she got older, she grew anxious about walking around her neighborhood.

Despite her concerns, Geraldine might have stayed in the condo longer were it not for an encounter with a particular neighbor, a young man who yelled at her. That was the last straw. In 2010, at 81 years old, Geraldine packed her bags and moved to a senior community.

Finally, surrounded by other seniors, in a quiet and peaceful community, she felt safe and comfortable. “She really enjoys being around people,” Joan says. She started going to regular potlucks and Wednesday night bingo.

Meanwhile, of course, her property tax debt on the condo piled up.

Geraldine Tyler (Photo courtesy of her niece, Joan)

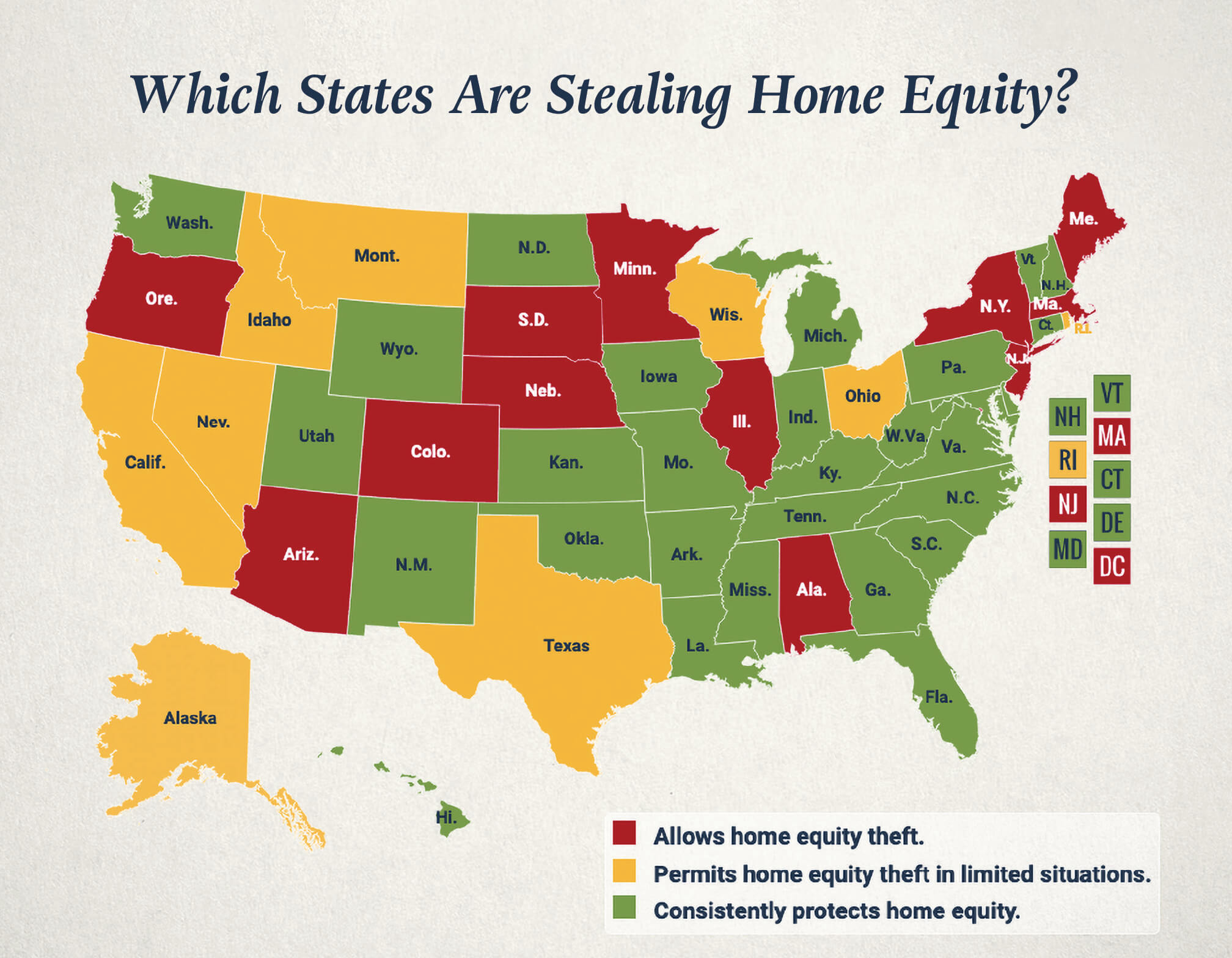

Home Equity Theft

At least a dozen states are guilty of allowing home equity theft, the seizure and sale of property to settle tax debts without returning surplus proceeds to the homeowner. Counties and cities will either sell foreclosed properties and keep the profits to pad their budgets—as happened in Geraldine’s case—or they’ll sell tax liens to private investors who then flip the properties for a tidy profit.

A Pacific Legal Foundation report found that between 2014 and 2020, Minnesota counties seized and sold at least 1,200 homes. These property owners lost not only their homes, but any equity they had saved up in the properties—and PLF’s research suggests the stolen savings amounted to an average of $207,000 per home in Minnesota, or 92% of the home’s total value. Nationwide, local governments wrongfully seized nearly $800 million in home equity during the same period.

As the AARP notes in an amicus brief supporting Geraldine’s case, home equity theft has a “devastating and disproportionate impact” on older homeowners.

Geraldine suffered a smaller monetary loss than many victims of home equity theft. The equity she lost was likely worth around $25,000. PLF client Alan DiPietro, an alpaca farmer in Massachusetts, lost more than $310,000 in equity after his town seized and sold his 34 acres.

And Geraldine, who has an extended family, is not in danger of becoming homeless—unlike, for example, PLF client Kevin Fair, a Nebraska widower who’ll have nowhere to go if he loses his small home and all the equity in it. Kevin only owed $588 in property taxes when the county sold his tax lien to a private investor for the amount of his debt; now that the investor has foreclosed on his home, he could be left with nothing.

“I’ll be homeless,” Kevin says. “Everybody in my family has passed away.”

For Geraldine, who enjoys playing bingo at her senior living community, being homeless is not at stake. And she is not interested in personal notoriety—she doesn’t even want to talk to the media. When PLF started working on her case on appeal and filed a cert petition at the Supreme Court, Geraldine was amazed that her case would be considered by the nation’s highest court.

Making it Right

When asked what she would do if the government finally pays her the $25,000 it owes, Geraldine doesn’t have any life-changing plans. Maybe she’d buy a new mattress, she says; she heard you’re supposed to buy a new one every 20 years.

But that’s not why she wants to win.

“It would mean a lot to me to win this case,” Geraldine tells PLF, “especially because it would help old folks like me.”

She’s right. Winning this case would prevent the government from stealing equity from other Americans—and as the AARP notes in an amicus brief supporting Geraldine’s case, home equity theft has a “devastating and disproportionate impact” on older homeowners.

When Michigan nursing assistant Tawanda Hall—another PLF client whose home equity was stolen by the government—heard that Geraldine’s case was going to the Supreme Court, she passed along a message of support and commiseration to Geraldine.

“I’m so sorry that after everything you’ve been through in your life that you still have to fight this battle at your age,” Tawanda said.

Tawanda knows how important the battle is: She fought and won her case against home equity theft in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, helping to put an end to home equity theft schemes in her home state.

Now Geraldine’s case could set a national precedent.

“I would love to see the Supreme Court end this practice,” Tawanda says, “because no one should go through losing all the value in their home. It’s totally unfair.” ♦

The Frontier Girl v. The New Deal

Nicole Yeatman

Managing Editor

It was a cold afternoon in October 1933, and Isabel Paterson was locked inside a New York City bank vault.

She was furious.

Then a 47-year-old columnist for the Herald Tribune, Isabel was at the bank to remove something from her deposit box. But the bank’s staff was concerned the withdrawal might violate one of President Franklin Roosevelt’s new banking rules. Roosevelt, sworn into office seven months earlier, had seized unprecedented executive authority over the banking system in an effort to end the country’s financial crisis. Less than a week after taking office, he’d rushed the Emergency Banking Bill through Congress so quickly that few congressmen had time to read it. Then he issued a series of executive orders that, among other things, forbade banks from allowing customers to withdraw currency for the purpose of “hoarding” and forced anyone with gold coin, bullion, or certificates to surrender them to the Federal Reserve.

Isabel’s bank was confused about Roosevelt’s new rules, which carried heavy fines and criminal penalties. So when Isabel appeared to be withdrawing possessions from her deposit box, the staff panicked. They decided to lock her inside the vault, unsure what else to do.

They’d probably picked the worst woman in America to hold prisoner.

Isabel stood only five-foot-three, but she was a terrifying force. Her brash manner had gotten her into the newspaper business decades earlier, almost by accident: In her twenties, she’d landed a job as secretary to a small newspaper publisher in Spokane, Washington, and promptly began terrorizing her new boss over his grammar. The publisher fired Isabel as his secretary—he needed someone “more tolerant,” he told her—and put her to work writing editorials instead.

It was an inspired decision: Isabel was a deft writer with an acerbic wit and strong opinions. She loved books, hated movies (called film a “monstrous” medium), vigorously opposed Prohibition (even though she rarely drank herself), worshiped “self-starters” like the Wright brothers, and, above all, believed that a nation’s strength was “directly proportional to the freedom of the individual.”

Now Isabel Paterson was locked in a bank vault—and it was Franklin Roosevelt’s fault.

Isabel began scolding the bank staff, loudly accusing them of kidnapping her. Stuck between Roosevelt’s regulations and Isabel’s ire, the bank apparently decided it feared Isabel more: They opened the vault and let her go.

Stuck between Roosevelt’s regulations and Isabel’s ire, the bank apparently decided it feared Isabel more: They opened the vault and let her go.

Afterward, of course, she wrote about the episode.

“There is practically nothing you can’t be put in jail for now,” she fumed.

Roosevelt, Isabel believed, was destroying America: Between the banking reforms, the agricultural price controls, and the creation of the National Recovery Administration, Roosevelt was setting up state machinery that had “the makings of Fascism” and was devaluing what little savings Americans still had.

“This bastard oligarchic half-state socialism we’re getting into looks to me like nothing but an everlasting mess,” Isabel wrote in a letter to a friend shortly after the bank incident. “[I]t won’t help or ‘save’ anybody in the end. It will just bring us all to the breadline.”

From the Stone Age to the Air Age

Isabel knew what it was like to be poor. She’d been born into poverty on the frontier.

She was Isabel Bowler back then, one of nine children of a not-very-successful Canadian farmer named Francis Bowler. The family moved around in a covered wagon in search of opportunities that never quite panned out, from a grist mill on Lake Huron to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to the Utah Territory to, finally, a ranch in Northwest Canada.

Isabel grew up teaching herself to read, sewing her own clothes, cooking bear meat, and churning butter. She was 16 years old before she saw an electric light bulb for the first time.

Years later in her column—where she always referred to herself as “we” rather than “I”—Isabel explained: “We weren’t brought up in a world in which water ran from taps and food came in tin cans, and we know that whatever is done, someone has got to do it.” In other words, she believed that a comfortable life “has to be earned and invented and made.”

When she was 18, she left home to make her way in the world, first as a “dining room girl” at a hotel, then as a stenographer for bankers, then as a secretary. She became Mrs. Isabel Paterson at 24 when she married salesman Kenneth Paterson, nicknamed “Pat,” in Calgary, Alberta. A couple weeks after marrying, Isabel took off for Spokane and left Kenneth behind.

It was in Spokane that she became a newspaperwoman, and several years later she made her way to the Herald Tribune in New York City. There she wrote a column on books, published several novels, and became a part of the city’s literary scene—a scene that, in the late 1920s and 1930s, was steeped in far-left politics. As she put it herself years later, “During the nineteen thirties… Communism broke out like hives among the ‘intellectuals’ and the scions and toadies of the rich.”

Looking back at the politically charged period—in which even people she respected were embracing statism—Isabel later quipped: “I was not a Communist. I am against organized corruption and planned murder.”

Isabel, of course, cut against the grain. From the moment she began writing her column, she published cutting reviews of popular intellectuals like Upton Sinclair and George Bernard Shaw. She noted that Shaw, who openly admired both Stalin and Mussolini, described his own workspace as a mess. “Now we can’t take any stock in the economics or social program of a man whose unconscious hope is to get the state to come in and sweep his room and trim his whiskers for him,” Isabel wrote.

When a novelist friend visited Rome in 1932 and wrote to Isabel that she was somewhat impressed by Mussolini, Isabel shot back that Mussolini was a “disgusting dictator.” Looking back at the politically charged period—in which even people she respected were embracing statism—Isabel later quipped: “I was not a Communist. I am against organized corruption and planned murder.”

Her attitude about freedom and progress is perhaps best captured in her writings about the Wright brothers, who completed their first flight in 1903 when Isabel was 17. To her, the brothers represented everything good about America. Orville and Wilbur Wright invented the airplane on their own, funded by about a thousand dollars of their own money, working on a private field that a farmer let them use. A separate, government-backed effort to develop the airplane was being run simultaneously by the head of the Smithsonian Institution; it blew through $50,000 of public money but produced nothing.

The Wright brothers, on the other hand, “were two Americans who asked nothing of anybody; they could earn what they needed, and mind their own business; and out of their native genius they solved a scientific problem which gave mankind the mastery of the air,” Isabel wrote.

She liked to say she’d lived “from the stone age to the air age.” She believed the airplane was invented in America “precisely because this was the only country on earth, the only country that has ever existed, in which people had a right to be let alone.”

Isabel Paterson with aviator Harry Bingham Brown.

Roosevelt Steps In

If the Wright brothers represented what Isabel loved best about America, Franklin Roosevelt came to represent what she most despised.

The crash of 1929 hit everyone, including Isabel: She lost money in the stock market and suffered a pay cut at the Herald Tribune. But she remained optimistic at first, having already lived through a depression in the 1890s. “Americans,” she wrote, “certainly are resilient.”

But Isabel quickly grew frustrated with President Hoover, who announced several dubious policies and programs after the crash (including the Farm Board, which paid farmers to grow unprofitable produce). So in the 1932 election, Isabel voted for Franklin Roosevelt instead.

Roosevelt, at least, said the right things on the campaign trail: He pledged to reduce “the annual operating expenses of your national government” and accused Hoover of piling “bureau on bureau, commission on commission.” He even compared federal commissions to “a fungus growth on American government.”

After Roosevelt took office on March 4, 1933, of course, he dropped all talking points about cutting the size of government.

In his first 100 days, Roosevelt pushed the First New Deal through Congress in 15 separate bills, including the banking reform bill. (“Congress doesn’t pass legislation anymore,” comedian Will Rogers joked at the time. “They just wave at the bills as they go by.”) The creation of the National Recovery Administration made a farce of Roosevelt’s campaign promises; suddenly federal codes dictated how many cents a laundry business in Cleveland could charge for pressing suits. Roosevelt’s appetite for expanding regulation clearly surpassed Hoover’s.

Isabel, of course, was disgusted.

At this point, she was under pressure to lay off writing about politics in her column. “[S]ome of Paterson’s readers were begging her to come down off her soapbox,” Stephen Cox, Isabel’s biographer, recounts. Her column, after all, was supposed to be a literary column; it was called “Turns with a Bookworm.” She’d already delved far more into politics than she probably should have. And the literary set was not particularly receptive to Isabel’s brand of free market individualism: Cox describes “the anti-capitalist mentality” of writers and public intellectuals during Isabel’s time as “even more entrenched than it is today.”

But Isabel ignored readers who complained, and used her column to make the case for liberty.

A long line of people gather for a food handout in Newark during the Great Depression in 1934. Source: Newark Public Library

Defending ‘Our System, Our Freedom’

In a December 1933 column, Isabel wrote:

A business may be so admirably organized that it looks as if it would run itself, but if you take out one or two men who keep it running and put in some bureaucrat who knows all the graphs and charts, the business will go to pieces. They don’t do it by rule, but by nature. And in an effort to regulate everything those people may be easily eliminated. They have been very nearly exterminated in Russia. Bureaucracy smothers them.

In a letter to a friend around the same time, she reflected on her own impoverished upbringing on the frontier. “[T]he poverty of my childhood was disagreeable,” she wrote, “but I don’t know what state action could have made my home happier; and all the chances and benefits I have enjoyed came from our system, our freedom[.]” Today’s men “all want to have their noses wiped for them by Mussolini, or Roosevelt, or somebody,” she complained.

Isabel published her own magnum opus in 1943, The God of the Machine, in which she offered an impassioned case for individual freedom as the engine of progress.

By 1935, Isabel was comparing the New Deal to “the procedure in Germany,” with its “usurpation of authority and disregard of the Constitution,” the “steady centralization of power,” and “a stupefying tangle of contradictory regulations of every activity of the private citizen.”

Franklin Roosevelt was president for 12 years—and for 12 years Isabel used her column as a pulpit to take an aggressive, principled stance against the New Deal and what it represented. When Roosevelt tried to pack the Supreme Court, Isabel defended judicial review; when Roosevelt introduced Social Security, Isabel slammed it as a “wage tax.”

She also took shots at First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who at one point lamented that houses out West were too far apart and that children who lived there must spend a good deal of time alone. “Should this be allowed to continue?” Isabel asked sarcastically.

[T]hose children… might find something to do without being told, think their own thoughts, read or observe nature, or get the notion of becoming independent, instead of planning to grow up and attach themselves forthwith to a government pay roll, where they can be assured of steady supervision and inquisition at intervals into their private lives.

A Legacy of Freedom

Isabel was eventually fired from the Herald Tribune over her unfashionable politics. The tide of opinion was trending the other way: Isabel’s own boss, for example, was the editor and assistant for Wendell Wilkie’s wildly popular 1943 book that called for a single world government. The Roosevelt administration also cultivated “inappropriately cozy relationships with journalists,” according to Goldwater Institute scholar Timothy Sandefur, and “those who resisted the New Deal learned that dissent was costly.”

But Isabel’s firing didn’t come until 1949, four years after Roosevelt died in office. She managed to hold onto her column far longer than anyone might have guessed, through her undeniable skill and strength of will.

Her legacy, of course, outlasted her column.

Ayn Rand, the Russian émigré author of The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged, and Rose Wilder Lane, author of The Discovery of Freedom, both became friends of Isabel’s during the 1940s. Isabel became a sounding board for both women and encouraged their individualist philosophies. Eventually her friendships with both women imploded—Isabel was, admittedly, a difficult person—but her influence is felt in Rand and Lane’s work.

“You have been the one encounter in my life that can never be repeated,” Rand wrote in Isabel’s copy of The Fountainhead.

Isabel published her own magnum opus in 1943, The God of the Machine, in which she offered an impassioned case for individual freedom as the engine of progress. Rand said the book “does for capitalism what Das Kapital does for the Reds and what the Bible does for Christianity.” It became a foundational text for a new, upcoming generation of conservative and libertarian leaders in America, including William F. Buckley and Russell Kirk, who both credited Isabel as an inspiration.

Isabel did not choose the easiest path for herself, even at the end: In retirement, she remained a staunch opponent of Social Security and refused to accept her own benefits. She kept her card in an envelope labeled “Social Security Swindle.”

As she wrote in a 1936 column: “Freedom is dangerous. Possibly crawling on all fours might be safer than standing upright. But we like the view better up there.” ♦

This article was inspired by the recent book Freedom’s Furies, published by the Cato Institute and written by Tim Sandefur, vice president of Legal Affairs at the Goldwater Institute. Tim is a longtime friend of PLF, where he worked as an attorney from 2002 to 2016, and we attribute him with our thanks.

The City Worker v. Seattle

Laura D'Agostino

Attorney

When Joshua Diemert began his employment with the City of Seattle, he was looking forward to a fresh start. But as time passed, he began to dread going to work.

Tensions were running high in the office. At one point, a colleague told others they should “get a guy to swing by when Josh is in the restroom and beat him bloody.”

He watched coworkers reject white applicants to City programs because, as one colleague told him, those applicants benefited from “white privilege.”

The problems started when Joshua objected to mandatory training and handouts from the City’s Race and Social Justice Initiative, a program codesigned by Robin DiAngelo, author of White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism.

As part of the initiative, city employees were required to attend multi-day workshops where facilitators taught that “racism is in white people’s DNA.” At meetings, employees had to identify themselves by their race. The City instructs all employees to view their work environment as a power struggle, where those with “privilege” and power must be held accountable to those the City has deemed “powerless.” The City also pressures employees to participate in affinity groups or “caucuses,” where membership is premised upon an employee’s race.

Joshua witnessed how the training was encouraging city employees to stereotype everyone, including themselves, by race. He watched coworkers reject white applicants to City programs because, as one colleague told him, those applicants benefited from “white privilege.”

So Joshua pushed back. He declined invitations to meet with the white caucus. He eventually told a senior officer in an email that race-segregated meetings were “blatantly racist.”

“Most people go with the flow,” Joshua says, “even if the flow is wrong. I’ve never done that.”

In response, Joshua’s coworkers called him a “white supremacist” and referred to him as the “reincarnation of the people that shot Native Americans from trains.”

Life as a Seattle City employee was becoming unbearable.

Joshua Diemert at his new home in Texas.

A Rough Upbringing

Joshua used to enjoy his job in human services. As a program intake specialist, he was part social worker and part data analyst. “I’m not necessarily normal,” he jokes. He likes to make graphs for fun. It probably runs in his family: His brother is a mechanical engineer and his grandfather built airplanes in his garage. The data part of the job appealed to Joshua’s nerdy side.

And the social work part—well, that appealed to a different side of him.

Joshua and his brother didn’t have a “Leave It to Beaver” childhood. Their father was an ex-biker who used drugs and hung with a rough crowd. Their mother and father were separated but still lived in the same house: Their mother lived upstairs and their father stayed downstairs. It was a dysfunctional environment, and Joshua struggled.

“I dropped out of school, ran the streets, and was incarcerated multiple times by the time I was 17,” Joshua admits. At the time, he felt like his behavior was out of his control—like his fate was predetermined.

But Joshua did not succumb to this sense of defeatism, as certain events in his life not only challenged him to reevaluate his initial assumptions but led him to set his sights on a new North Star. First, during one jail stint, he went on a reading spree: He read the Bible cover to cover and discovered the writings of Norman Vincent Peale, Booker T. Washington, and Thomas Sowell. He started reflecting on personal responsibility and free will.

It was on the heels of this ideological shift that Joshua experienced a personal tragedy. When he was out of jail, he lived with his girlfriend’s family, including her eight-year-old sister, Jessica. The girls’ mother was a drug addict who behaved erratically. One night, the mother stabbed Jessica to death. This unfathomable and senseless murder affected Joshua profoundly—especially after the mother called home from jail and spoke to Joshua.

“She blamed everyone but herself for Jessica’s death,” Joshua says. “She didn’t take any responsibility for her own actions.”

The awful incident brought weight to the ideas Joshua had studied in jail: Personal responsibility was no longer a mere concept, but held the gravity of life or death. Joshua knew he had to take responsibility for his life and affirmatively rejected what he calls “the victimhood mindset” that had shaped his youth and adult life. He started to work hard. He married his girlfriend, and they had a daughter—but when his wife followed in her mother’s footsteps and began abusing drugs, Joshua cut ties and became a single father. While raising his daughter, he enrolled in college and graduated cum laude, and later managed to buy a small home. He met a single mother, Christina, who shared his ambition for a better life. They started flipping houses together and became a family.

“The values I embraced led to success,” Joshua muses, “while the mentality I held as a juvenile delinquent was destructive.”

By working at Seattle’s Human Services Department—which has an annual budget of over $300 million—Joshua hoped to help struggling city residents get their lives back on track, just as he’d helped himself.

But then he and his coworkers got sucked into the City’s Race and Social Justice Initiative (RSJI) training.

The Influence of Robin DiAngelo

In Chapter One of her mega-bestseller White Fragility, Robin DiAngelo says that “like most white people raised in the U.S.,” she was taught not to see herself in racial terms or behave as if her race mattered. But that’s wrong, she argues. We need to “sit with the discomfort of being seen racially, of having to proceed as if our race matters (which it does).”

To DiAngelo, “Western culture” is problematic because it values the individual over group identity. Individualism “reinforces the concept that each of us is a unique individual and that our group memberships, such as race, class, or gender, are irrelevant,” she complains. We need to reject our society’s emphasis on individuality and instead “grapple with how and why racial groups matter.”

When the Seattle mayor’s office appointed DiAngelo to codesign the City’s RJSI training, DiAngelo embedded her race-based, anti-individualist ideology into the program.

In fact, DiAngelo says in her Author’s Note, “temporarily suspending individuality to focus on group identity is healthy for white people.”

DiAngelo has built a cottage industry out of this nonsense: She charges $14,000 per speech and reportedly nets over $700,000 per year. Her clients include universities, Fortune 500 companies, public school systems, and—of course—cities.

The City of Seattle was essentially DiAngelo’s first client: Her 2004-2007 partnership with the City predates the publication of White Fragility and the massive fame that came with it. Back then, DiAngelo was a lecturer at the University of Washington with a just-earned Ph.D. in multicultural education; but she was already promoting ideas that would later form the basis of White Fragility. When the Seattle mayor’s office appointed DiAngelo to codesign the City’s RJSI training, DiAngelo embedded her race-based, anti-individualist ideology into the program.

And when Joshua started working for the city in 2013, he and other employees were required to participate in the training.

Speaking Up

Joshua found some of the training materials downright baffling.

One handout referred to a “focus on individualism” as a “common pattern of whites.” Another listed “believ[ing] that there is such a thing as objectivity” as a “manifestation of white supremacy culture.” (Also listed: an “emphasis on being polite,” a “focus on timelines,” and “valu[ing] written communications.”)

“I really dug into their material,” Joshua says. “They actually believe that meritocracy is a system of white supremacy.”

The race-segregated meetings also bugged him—why was he receiving invitations to gather with other white people to discuss “whiteness”? If the goal was to defeat racism, wasn’t grouping people by race counterproductive? Instead of encouraging City employees to treat people as individuals, Seattle was teaching that race was what mattered most.

Joshua could have kept his nose down, completed his mandatory workshops, and allowed the RJSI training to go unchallenged. He had every incentive to keep quiet: His annual review included an evaluation of his participation in the training. And RSJI materials made it clear that failing to adequately respect “anti-racist institutions and policies” was a form of “anti-blackness,” as one PowerPoint put it. If he objected to the training, Joshua would be painting a target on his back.

But nodding along with something wrong wasn’t in Joshua’s nature—and the RSJI training went against everything he’d learned in his own life.

“The choices I made [as a youth] led to my hardships,” Joshua says. “Recognizing my role in it all is empowering because it means, as an individual, I also have the power to choose success. The City of Seattle wants to deprive people of this power and make them focus on factors they can’t control. They’re telling people they don’t have a choice—it’s all predetermined by your identity. This is hopeless and false.”

He decided to speak up against the training.

“Good Morning,” Joshua wrote in an email to a union representative.

I have issues with some of the mandatory training we have to attend as an employee of Seattle. Is there a way we can have a meeting? Some of it has to do with the material being taught, which I have found to be extremely racist as it blankets entire groups of people with stereotypes based solely on the quantifier of skin color… In my RSJI classes, a few of the things that the instructors have taught are:

- The 13th Amendment is racist and a tool of enslavement

- Wealth redistribution is the only mechanism to fix the issues at hand

- Individuality or the want to always better yourself are tenets of white supremacy

- Looking at the content of character and being colorblind is a tenet of white supremacy

The union representative didn’t prove helpful. So Joshua tried other avenues. In an email to a senior officer, Joshua wrote that “all of the Race and Social Justice training, including the affinity caucuses, are blatantly racist, stereotype people based on superficial characteristics and apply negative attributes to entire groups of people based off the color of their skin.” He asked for permission to create his own non-race-based group. The City denied his request.

In another email, to a colleague, Joshua defended his decision to speak out. “I have been taught in my mandated anti-discrimination classes to stand up to racism when I see it, so that is what I am doing,” he wrote. “I am standing up to racism.”

His colleagues did not react well. There were threats, accusations, and whispers. At one point a colleague chest-bumped Joshua, got in his face, and told him he had white privilege.

In an email exchange about Joshua, one of Joshua’s coworkers told another: “I look at this stuff like a war. Some people may think that education and talking people through this stuff will do it, but I don’t.”

Eventually, Joshua felt he had no choice but to quit his job. It was hard for him; he cared about his work. But the situation had become untenable. He stopped working for Seattle, then left the city altogether. He now lives in a small town in East Texas.

But he hasn’t given up.

Pacific Legal Foundation is now representing Joshua in a lawsuit against the City of Seattle for imposing hostile workplace conditions based on race. His lawsuit could change the mandatory training for Seattle’s 10,000 city employees, ensuring others aren’t subjected to race-segregated meetings.

His lawsuit could change the mandatory training for Seattle’s 10,000 city employees, ensuring others aren’t subjected to race-segregated meetings.

In the 15 years since Robin DiAngelo completed her contract work for Seattle, she’s become a dazzlingly successful author and lecturer. Her work has been read by—and assigned to—millions.

Meanwhile, in Seattle, violent crime has gone up since 2007. So has homelessness. If the Race and Social Justice Initiative training is meant to help city employees better serve the city, its effectiveness is not clearly reflected in city trends.

After watching White Fragility skyrocket up The New York Times’ bestseller list in 2020, journalist Matt Taibbi puzzled at DiAngelo’s success. Her work is “urging us to put race even more at the center of our identities,” Taibbi wrote, “and fetishize the unbridgeable nature of our differences… It’s almost like someone thinks there’s a benefit to keeping people divided.” ♦

The Landlords v. Alameda County

Brittany Hunter

Editorial Writer

Jon Houghton

Attorney

John Williams was at the end of his rope.

The duplex he owned in Oakland, California, was supposed to be his ticket to a better life. He’d bought it in 2004, only five years after he’d come to the Bay Area as a friendless, homeless yoga teacher. The house was John’s success story: It was now worth a decent amount of money. He was renting it out to tenants, but when he was ready to sell, he’d have enough savings to move to Savannah, Georgia, and open a small flower shop.

That was John’s dream: leaving California to start a new chapter of his life in historic Savannah. For years, it was a hypothetical fantasy. Someday, he thought, when the time is right…

Then, in January 2020, basketball great Kobe Bryant died in a helicopter crash. John thought, “Damn. Life really is short, even with a lot of money.”

He started making plans to move, even telling his boss that he planned to be on his way to Georgia by “the end of March.”

But March 2020 was when COVID-19 came to America. Everything ground to a halt. On March 31, the Alameda County Board of Supervisors—which oversees a population of 1.6 million, including Oakland—announced a countywide eviction moratorium: No landlord would be allowed to evict a tenant, even if the tenant stopped paying rent.

John’s upstairs tenant wasn’t a problem; he was John’s nephew. But the downstairs tenant, Mary (not her real name), a single mother with two kids, was always late with the rent.

After the moratorium went into effect, Mary stopped paying rent altogether.

As “two weeks to flatten the curve” turned into months, John’s own financial situation was hanging by a thread. Without the ability to collect the rent, he was forced to begin pulling money out of his 401(k) to pay the bills. Meanwhile, when he visited the property, he realized that Mary was running a storage business out of her unit and had even changed the lock to the back gate. It seemed she was taking advantage of the moratorium to turn a profit with her rent-free living situation.

John’s only hope was to sell the duplex. In December 2020, believing the moratorium would soon be lifted, John put the house on the market and quickly found a buyer. In preparation for the sale, he gave notice to his nephew and roommates, and they soon moved out of the top unit.

But Mary refused to leave.

Eager to be done with the property, John offered Mary $30,000 and full forgiveness of her back rent if she agreed to move out. She refused. Her attorney emphatically told John that she would not be leaving unless she was given $190,000. Concerned by the situation, John’s buyers backed out of the deal.

John felt like he’d lost control over his life. “I was losing my mind,” he says.

Landlord John Williams on the steps of his Oakland duplex.

‘Cry Me A River’

California is consistently ranked one of the worst states in the country to be a landlord. There’s state-wide rent control, caps on application fees, and—where there’s not an outright moratorium—strict rules for the eviction process. In December 2022, Alameda County even became the first county in the country to prohibit landlords from doing criminal background checks on tenants.

Then there’s the anti-landlord sentiment.

“Landlords need to stop whining about the unfairness of California’s eviction ban,” Los Angeles Times columnist Erika D. Smith wrote in August 2020. Landlords, she said, benefit from a system that has “long been tilted in their favor.” She argued that giving in to landlords would be unfair to renters, “many of them black and Latino.” (Since it apparently matters to Ms. Smith, it’s worth noting that John Williams is black, as are the other landlords featured in this article.)

A realtor tried to defend landlords in an October 2020 CityWatchLA op-ed titled “Landlords Are Not the Devil.” She expressed her dismay that #KilltheLandlords and #EattheLandlords had trended on social media.

“Cry me a river, greedy landlords,” one commenter replied.

The Bay Area is especially hostile. Even before the pandemic, people in Oakland and San Francisco tended to treat landlords as an enemy oppressor. “I’ve suddenly become a bad word in this town,” a San Francisco landlord wrote in 2014. “I’ve gone from living as a conventional citizen in a city that has always felt welcoming to being unable to ignore the new sentiment of a seeming majority that’s turned against me.”

Alameda County’s eviction moratorium is absolute: Landlords cannot evict tenants, period. It doesn’t matter if a tenant hasn’t paid rent in a year. It doesn’t even matter if a tenant is violent—as some landlords have unfortunately discovered.

Sheanna and Karl’s Story

Sheanna and Karl Rogers thought they had attained their American Dream when they bought their first home as a young married couple. After two kids, and with another baby on the way, the Rogerses decided to move into a bigger home—but they kept the first house as a rental property.

Years later, Karl lost his job. When trying to decide what to do next in his professional life, Karl proposed to Sheanna that they turn their rental property into a residential care home for adult males with mental health issues. The project was close to Karl’s heart: His brother has schizophrenia.

The couple worked with an agency to fill the home with residents. But the care facility took up only part of the house: There was also a small studio apartment attached to the home. In 2018, a childhood friend of Karl’s, Ryan (not his real name), asked the Rogerses if he could rent the studio for $1,000 per month. They said yes.

“It was supposed to be temporary, until he could land on his feet,” Sheanna says. “Temporary turned into a nightmare.”

Even before the pandemic, people in Oakland and San Francisco tended to treat landlords as an enemy oppressor.

The couple began receiving reports that Ryan had offered meth to residents of the care facility. Worse, Ryan was hostile and threatening. At one point, he pulled out a gun and started waving it in the air while screaming obscenities at the house manager, who just so happened to capture the incident on camera and alerted the police.

But the most frightening moment came in January 2019, when Ryan beat one of the residents with a crowbar. Ryan was arrested and put in jail—but only for a few days. Then he was back at the house.

“He didn’t go to jail for long,” Sheanna said. “That’s a problem out here, too.”

Sheanna and Karl had had enough. They started eviction proceedings. This was long before the pandemic, but even back then, evictions were difficult in California. The process took time.

Months went by. Meanwhile, whenever Ryan saw the Rogerses, he would get in their faces, hurling spine-shivering threats. He once warned, “Keep on pushing this eviction thing and you are going to find yourself six feet under.” At one point, Sheanna’s brother was on the property and heard Ryan on the phone telling the other caller, “Oh yes, they think I’m playing with them. I’ve killed people before. I will hurt them.”

Finally, in February 2020, a court issued an eviction order. Ryan would have to be out by April 1. Sheanna and Karl were relieved: Their nightmare would soon be over.

But in March, the county announced the moratorium.

“I’m not going anywhere,” Ryan told Sheanna and Karl. “So you might as well get ready.”

Sheanna and Karl were helpless. Even though they had a signed eviction order, and even though Ryan had been arrested for attacking a resident at the care facility, the moratorium meant Ryan could continue to live in the Rogerses’ home.

Worried about the other residents’ safety, Sheanna and Rogers closed down the care facility. They didn’t know what else to do. Ryan refused to leave. He was living rent-free in their home and had forced them to shut down their business. Sheanna and Karl had to borrow money to pay for the mortgage and utilities. Ryan, on the other hand, seemed to be flourishing: He bought a boat and a car.

“I can’t get him out of my house,” Sheanna says. “I own the house.”

She and Karl did everything right: They worked hard, put down roots, and were achieving the American Dream. “And now it seems like the government has stolen it from us,” Sheanna says.

Jackie’s Story

Becoming a landlord used to be a way for middle-class Americans to achieve lasting financial stability.

Jackie Baker knows that firsthand: Her mother was a nurse in the 1960s who worked while raising two daughters. For a black woman in those days, buying property wasn’t easy. But with the help of a fellow nurse, she managed to buy a small rental property on 92nd Avenue in Oakland.

The property was successful, and Jackie’s mother was a good landlord. She eventually bought several other rental properties, creating a legacy for her children.

But it was that first property, on 92nd Avenue, that meant the most to Jackie. She can still remember playing jacks on the floor of the house while her mother painted the walls.

When Jackie’s mother passed away, the properties were divided between Jackie and her sister. Jackie inherited the house on 92nd Avenue. It had a tenant, Sam (not his real name), who seemed to pay the rent on time.

The day Jackie was supposed to have her seventh court appearance was the day the court shut down for COVID.

But suddenly, more than a year after Jackie took over the property, Sam stopped letting her in the house to do repairs. Jackie had to go to court to win the right to enter her own property—and because this was California, the process took a long time.

Finally, after four years and several court appearances, she was allowed into the house.

“When I got into the property, I almost fainted, literally,” Jackie says. “It was destroyed.”

The walls of the unit were layered with tobacco and what was either dog or human feces. The hardwood floors and cabinets were destroyed. He had even broken all the shelves with the sledgehammer.

To fix what had been done, Jackie was going to have to pay nearly $100,000.

The situation only got weirder.

One reason Jackie wanted to get inside the apartment was because Sam had covered his windows with tinfoil, which seemed suspicious. Jackie used to work in law enforcement; she recognized the signs that someone might be cooking meth.

This was long before the pandemic: Jackie started the process of evicting Sam in 2017. But the process dragged.

The day Jackie was supposed to have her seventh court appearance was the day the court shut down for COVID.

“By the time the pandemic happened, he should have been gone,” Jackie said.

Instead, once the moratorium went into effect, Sam was able to stay in the property he’d destroyed—and now he was able to stop paying rent. His lawyer even tried to demand that Jackie pay $10,000 for Sam to move.

Jackie thought it was crazy.

“The government is saying, ‘Hey, we need your property taxes,’” she points out. “And the banks are saying, ‘Hey, we need your mortgage payments.’ But then Alameda County is saying, ‘The renters don’t have to give you this money that allows you to make these payments.’”

Like other landlords, Jackie figured the moratorium would be short-term. But months passed—then years.

“Every time they extended it, it was like they slapped you in the face,” she says.

Jackie Baker

Sheanna Rogers

Fighting Back

The deck was stacked against John Williams, Sheanna Rogers, and Jackie Baker.

They were all losing money. John was losing his dream of moving to Savannah. Sheanna had lost her residential care facility. Jackie was losing her mother’s legacy. But the Alameda County Board of Supervisors didn’t seem to care.

Sheanna went to a Board of Supervisors meeting. Listening, she thought: “Is there not one person who sits on this board who owns a property?”

John was discouraged. Last year at one point, he thought he was having a heart attack. When he went to the emergency room, the doctors told him it was a panic attack. The stress had gotten to him.

Jackie says a lot of landlords have gone into foreclosure. The county is treating landlords “like we have endless pockets,” Jackie says, “and we don’t.”

With Alameda County refusing to end the moratorium, and little sympathy from the community, John, Sheanna, and Jackie might have given up. If they tried to fight the eviction moratorium in court, their chance of success was slim.

They decided to fight anyway.

With Pacific Legal Foundation’s help, and with two other landlords joining them as plaintiffs, they sued the county, arguing the moratorium violates the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause. The government cannot force property owners to keep unwanted tenants who have stopped paying rent, attacked other residents, or destroyed property. Doing so constitutes an uncompensated “taking” of the property, because the government—not the property owners—is deciding who gets to live there.

PLF’s motion for summary judgment was denied in November 2022, a heartbreaking but not-totally-unexpected setback. John, Sheanna, and Jackie are fighting an uphill battle.

“I’m trying to figure out, how do I hold on?” John says. “It’s been three years of no rents at all in my property. That’s where I’m at now.”

At one point during this exhausting ordeal, Sheanna made a passionate plea to a judge, who sympathized with her situation and told her, “These are the kind of things that don’t let me sleep at night. This is why I don’t like this moratorium. These are the hard things that I have to struggle with.”

The judge acted like “his hands were tied,” Sheanna remembers. It felt awful to appeal for justice and get only sympathetic words in return. She wanted things to be set right—not just for her, but for all landlords.

Jackie, too, is fighting for more than just herself. Because she inherited the property on 92nd Avenue from her mother, who had it for decades, there’s no mortgage on the property. In many ways, Jackie is more fortunate than others. But having grown up watching her mother become a successful landlord in Alameda County, Jackie is fighting for the broader principle at stake. If this injustice is allowed to continue, who in the county would ever want to risk renting to tenants again?

“I want to stay in this fight as long as they’ll allow me to stay in it,” she says.

Once when Jackie went to the grocery store, activists approached her with a clipboard and asked her to sign a petition for renters’ rights. She thinks that because she’s black, they assumed she’d be on their side.

Instead, she squared her shoulders and told them, “I’m a landlord. I’m not signing anything.” ♦

PLF is not using the tenants’ real names out of concern they might retaliate against our clients, who have suffered enough.

The Lawyers v. The Government

Chad Wilcox

Chief Operating Officer

To leave a good job and create a new organization, you have to be bold. You’re giving up security for something untried. You’re exchanging a certain paycheck for the possibility of failure.

That’s doubly true if the job you’re leaving is in the government, which brings not just a paycheck but also the guarantee of influence. That’s why so many government employees—including members of Congress—stay in government their whole professional lives. Being able to shape law and policy from the inside is a powerful privilege that’s hard to give up.

But 50 years ago, a small group of lawyers left the administration of California Governor Ronald Reagan to create something new: Pacific Legal Foundation, the nation’s first liberty-based public interest law firm.

It was an experiment. Reagan aide Ronald Zumbrun had drafted a 53-page proposal to show how the group could advance liberty by representing individuals brave enough to sue the government. Instead of shaping law and policy from the inside, the attorneys would target and challenge government actions that were a threat to Americans’ life, liberty, and property. Instead of having government resources at their disposal, the attorneys would now have the apparatus of the state—with its deep reserves of time and budget—aimed against them.

On March 5, 1973, PLF incorporated in Sacramento with a starting budget of $117,000.

Three years later, Barron’s published a feature article about the fledgling law firm. “PLF’s secret weapon is its team of brilliant trial lawyers, who in less than three years have gone into courts all over the country to win 25 victories,” the magazine wrote. The firm’s budget had grown to almost a million dollars, thanks to the growing community of PLF donors.

At that point, PLF staff was largely composed of former government employees. “One thing we all have in common is that we’ve all at one time or another been connected with government and have first-hand knowledge of the workings of bureaucracy,” Zumbrun, then PLF’s president, told Barron’s.

Now, as PLF celebrates its 50th anniversary, the staff still includes some former government employees—but most have come to PLF from elsewhere. One attorney used to work as a geologist; another was a musician; another once traveled the country as an adventure tour guide. Several attorneys came from private practice, including corporate law. Last year, a lawyer gave up being partner in his own firm, which he’d built up over 17 years, to join PLF.

All have come with a common purpose: to stand alongside people willing to step into battle against unjust government.

“Many see the Sacramento-based Pacific Legal Foundation as a knight jousting the unbeatable ogre of Big Government,” a California newspaper wrote in 1987, the year PLF won its first Supreme Court case.

Today PLF is a nationwide organization with over a hundred staff working from 23 states. The work has paid off at the highest level: PLF has won 14 Supreme Court cases and is litigating three more cases at the Court this term—which means our 50th year might be the most effective in PLF history.

In 1973, a small group of attorneys took a risk in founding PLF, and because they did, countless Americans over the years have been empowered to stand up for freedom—with PLF at their side. ♦

PLF celebrates the

extraordinary generosity of

The Quarter Century Club

Pacific Legal Foundation is honored to recognize our new class of donors who, as of 2022, have supported PLF’s efforts to stand in the face of big government giants for 25 consecutive years.

They join the 217 donors who are already Quarter Century Club members. This extraordinary commitment to our mission of defending liberty and justice for all deserves our deepest gratitude.

Thank You!

Mr. Carlyle K. Bailey

Mrs. Carol L. Bremer

Mr. John B. Crowell, Jr.

Florida Farm Bureau Federation

The Thornton S. Glide, Jr. and

Katrina D. Glide Foundation

Mr. Stanley K. Hamilton

Mr. and Mrs. Arvid J. Myhre

Mr. Warren T. Riley

Ms. Janette L. Smith

Mr. Paul T. Southgate

Mr. and Mrs. Rudy Staedler

Mrs. Rieta M. Walker

Mr. Jonathan D. Wexler

Mr. Carlyle K. Bailey

Mrs. Carol L. Bremer

Mr. John B. Crowell, Jr.

Florida Farm Bureau Federation

The Thornton S. Glide, Jr. and

Katrina D. Glide Foundation

Mr. Stanley K. Hamilton

Mr. and Mrs. Arvid J. Myhre

Mr. Warren T. Riley

Ms. Janette L. Smith

Mr. Paul T. Southgate

Mr. and Mrs. Rudy Staedler

Mrs. Rieta M. Walker

Mr. Jonathan D. Wexler