Winter 2023

Blueberry pancakes. Fondue. Homemade pizza. Red Ryder. Each of those things may seem different from the others, but there’s a common thread to them all, at least in the Anderson family. They’re the distinctive meals we eat and the movie we watch consistently every Christmas. In fact, it wouldn’t really be a true holiday celebration without these traditions. Given the timing and theme of this issue of Sword&Scales, it seems the perfect opportunity to give insight into some of my own family’s customs.

The pancakes have the most interesting backstory. In Anderson parlance, we call it a “Bala Breakfast,” in honor of the small town in Ontario (named after a small town in Wales) where my wife’s family had a cottage for a century or so. It’s also where the recipe was honed, on a decades-old electric stove whose controls were less than intuitive. But honed it was, exported back to the States, and is now the meal we have on Christmas mornings—together, when we can find it, with Canadian peameal bacon. And, in times where we’ve thought ahead, it’s all served with whipped honey and toasted scones from Don’s Bakery on Muskoka Road 169.

But the season’s not just about carbohydrates. Our Christmas Eve dinner for the past several years has been beef fondue, cooked in oil and garlic. As a son of the 1970s, I come by my interest in fondue honestly. What’s most special is the communal (and primordial) nature of fondue, with all of us sitting around a boiling pot waiting for our speared meat to cook. We serve the beef with some sauces on the side, the favorite of which is freshly made hollandaise (pronounced without fail with the same emphasis and excitement as the hit Madonna single, “Holiday”). And, should anyone lose their food from their fork in the pot, they have to kiss the person on their left. It also means a lot of “accidental” losses by the kids who find this part of the tradition hilarious. We cap off the evening with Christmas crackers, another tradition we’ve imported from abroad, this time across the Atlantic.

The third part of the Christmastime trifecta of food is grilled pizza (back to carbs). For this meal, which we have on Boxing Day (yet another British connection), we partially cook the dough on the outdoor grill, bring it inside to cover in toppings, then grill it again until ready to be sliced. As a parent of two elementary school-aged boys, it’s a fun exercise in creativity for the whole family. Plus, you get pizza in the end.

There’s one final piece to this feast, but this one’s for the eyes and not the belly. It also comes from my own childhood. All day on television, playing in the background, is the great movie masterpiece from 1983, A Christmas Story. While it’s typically screened only in December, it’s a movie whose witty script pops up in our household throughout the year. Whether it’s Ralphie yelling “Oh, fudge!” or Randy shrieking, “I can’t put my arms down!” or the Old Man confusing “fragile” for the Italian “fra-gee-lay” or the Mother’s “everybody knows” the Lone Ranger’s nephew’s horse is named Victor, the words and phrases have entered the Anderson lexicon in a way like no other movie. On my last trip to Cleveland, I didn’t visit the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. No, I stopped by Higbee’s department store and the Christmas Story house (which is on 11th, not Cleveland, Street).

I wish each of you a wonderful holiday season filled with your loved ones and all the goodness—whether caloric, cinematic, or otherwise—that you can find. And may 2024 be even better than 2023.

Steven D. Anderson

President & CEO

“The word kith is Old English, and the original senses were ‘knowledge,’ ‘one’s native land,’ and ‘friends and neighbours.’ The phrase kith and kin originally denoted one’s country and relatives.”

OXFORD DICTIONARY

These Parents Did Not Hurt Their Children—But Child Protection Agencies Targeted Them Anyway

Glenn E. Roper

senior attorney

AT 2:07 A.M. on Saturday, July 16, 2022, Sarah Perkins texted the family group chat: CPS just took custody.

Her sister-in-law Dia wrote back: No no no no.

Custody of both kids? Her brother-in-law Brian wanted to know. At 1:00 in the morning?

They drove off with both kids, Sarah wrote. Clarence screaming I don’t want to go in their car. They didn’t have paperwork even.

An Emergency Room Visit

THREE DAYS EARLIER, Sarah, a Ph.D. student in Waltham, Massachusetts, had taken her three-month-old baby, Cal, to the emergency room after his fever spiked to 103.6 degrees. Her husband, Josh Sabey, a documentary filmmaker, stayed home with their older son, three-year-old Clarence.

At the hospital, doctors ordered x-rays to rule out bronchiolitis and discovered Cal had two partially healed rib fractures. Neither Sarah nor Josh had any idea how the rib fractures happened. When the hospital social worker talked to Sarah about the injury, Sarah was more concerned about Cal’s fever—he did have bronchiolitis, it turned out. The social worker probed the family’s home life, asking Sarah if her husband “often ignored” their children. She didn’t like Sarah’s response. [T]he mother rolled her eyes, the social worker reported to the Massachusetts Department of Children and Families, the state’s child protection services agency.

Two DCF officers came to the hospital and questioned Sarah. Josh brought Clarence to the hospital so DCF could talk to the toddler.

Do your parents ever hurt you or your brother? the officers wanted to know.

Clarence told the officers his parents didn’t hurt him. They put me in timeout sometimes, he added.

After spending 48 hours in the hospital, Sarah and Cal finally were allowed to go home on a Thursday afternoon. They woke up at home Friday morning, relieved to be back in their normal life. DCF hadn’t yet closed their investigation into Cal’s fractured ribs—one of the DCF officers, a man named Axel, stopped by the house unannounced Friday evening around 5. But Axel was reassuring: He doubted there would be any criminal charges filed against Sarah and Josh over the injury. In his notes from the home visit, Axel described a happy family scene. “Clarence was walking around and smiling,” he wrote.

Eight hours later, in the middle of the night, the police knocked on Josh and Sarah’s door. With them were two new DCF officers Josh and Sarah had never seen before.

They’d arrived to take custody of Clarence and Cal.

A Bureaucrat’s Decision

JOSH AND SARAH later found out that while they were relaxing at home on Friday, DCF’s “area program manager”—a woman named Kate who’d never met Josh, Sarah, or their kids—was busy reviewing the family’s file.

Kate was concerned about “limited visibility” of the children: It bothered her that Clarence and Cal didn’t go to daycare where teachers could keep an eye on them. It also bothered her that the hospital diagnosed Cal’s fractures as likely being caused by “non-accidental trauma.”

On Friday afternoon, Kate called a lawyer for a consult. The phone call is redacted in the government’s records, but judging by events following the call, it seems Kate was asking whether DCF could legally take custody of Clarence and Cal.

The lawyer’s answer must have been yes.

DCF didn’t bother to obtain a warrant. They didn’t make their case to a judge. Instead, a mid-level bureaucrat who’d never met the family decided, after looking at paperwork, to dispatch officers in the middle of the night and separate two young children from their parents.

DCF at the Door

JOSH TRIED to keep his voice even. “Do you have a warrant?” he asked the police and DCF officers.

Sarah, who’s normally quiet with a gentle voice, was hyperventilating. She started filming the police with her phone, demanding their badge numbers. Josh’s mother, Lisa, who was staying over that night, was shaking with anger.

“I’ve never seen my mom like that,” Josh says. “Almost crazed.”

Josh is not the violent type. If the DCF bureaucrat who ordered his kids’ removal had bothered meeting him, she might have known that. Once, when Josh’s sister was dumped by her husband out of the blue, Josh calmly drove the soon-to-be-ex to his new house and pleasantly said goodbye. Afterward, he thought: If I ever had a chance to punch someone, that was it. But it wasn’t his instinct to fly off the handle—not even with DCF at his house in the middle of the night.

So he stood in his front doorway, with his wife and mother behind him and his young children asleep inside, and he tried to reason with the officers.

The police admitted to Josh they didn’t have a warrant.

“I kept saying, ‘We have basic constitutional rights. You can’t just come here and demand our children,’” Josh remembers.

A mid-level bureaucrat who’d never met the family decided, after looking at paperwork, to dispatch officers in the middle of the night and separate two young children from their parents.

In an exchange captured in Sarah’s recording, a police officer told Josh there was an emergency order allowing DCF to take custody of Clarence and Cal.

“So you can take kids without a judge?” Josh asked.

“Yes,” the officer replied. “I’ve done it before.”

Two of the police officers looked at their feet the whole time, like they were ashamed. Josh kept asking them how it could be legal to take children from their parents without a warrant. One of the DCF officers said she didn’t want to be “videoed.” But they were intent on taking custody.

When it became clear the police would forcibly enter the home to get the kids if necessary, Josh asked Sarah to wake up Cal and breastfeed him.

“That felt like defeat,” Sarah says.

She fed Cal and pumped extra breastmilk for DCF to take. Both boys have dairy allergies; Clarence is allergic to eggs and tree nuts. Added to the fear of losing the boys was another fear: What if DCF accidentally fed them the wrong thing?

“If Clarence eats eggs, he’s dead,” Sarah says. DCF assured her and Josh that they would come up with a meal plan in the morning.

After feeding Cal, Sarah reluctantly woke up Clarence.

“I sat on Clarence’s bed, and I rubbed his back,” Sarah remembers. “And I said, ‘My boy, you get to go on a car ride to a new place and make new friends. And Mom and Dad are going to come find you as soon as we can.’”

Clarence, sleepy and confused, didn’t want to go with the strangers. He began crying, then screaming and thrashing.

“It took forever to get him in the car,” Sarah remembers.

The family’s neighbor, Blanca, came outside after hearing the commotion. Sarah went over to her and burst into tears.

“I couldn’t bring myself to watch them drive away,” Sarah says. “And so Blanca was holding me and stroking my hair while the car drove away. And they were gone.”

Sarah hadn’t stopped her recording. There was no video at this point—the phone must’ve been in her pocket—but on the audio you can hear Sarah’s sobs: out of control, like she was breaking into pieces, like she couldn’t catch her breath.

“Blanca,” she said at one point. “They took both of my kids. They took them away.”

When Child Protection Agencies Are Wrong

ONE OF NETFLIX’S most popular documentaries in 2023 was called Take Care of Maya. It’s about a couple, Jack and Beata Kowalski, who were falsely accused of medically abusing their daughter Maya after they took her to the ER for a complex illness. Child protective services took custody of Maya. During one hearing to try to get Maya back, Beata asked authorities for permission to hug her daughter. She was denied. Losing hope, and having been separated from her daughter for 87 days, Beata committed suicide.

“This is one of the most screwed-up parts of the United States system, period,” an advocate says in the opening lines of Take Care of Maya. “Parents have no rights.”

Josh Sabey and Sarah Perkins are now part of a terrible club of which no one wants to be a member: innocent parents who’ve found themselves in the crosshairs of child protective services.

Sarra L. in Tucson, Arizona, is also in that club. She let her seven-year-old son and his five-year-old friend play by themselves at a public park while she went shopping at a nearby grocery store. Sarra’s friend was teaching a Tai Chi class at the park. The kids were safe. But police charged Sarra with contributing to the delinquency of a minor; then the Arizona Department of Child Safety listed Sarra on its Central Registry, preventing her from working with children. Pacific Legal Foundation helped Sarra challenge the unconstitutional registry in court. “This case is fundamentally about a parent’s liberty to raise her child,” PLF’s opening brief in Sarra’s case argued. In response to her lawsuit, the Arizona Department of Child Safety dropped Sarra’s name from the registry.

Josh and Sarah’s case is extreme. Their children are so young, for one thing. But it’s also how DCF handled the kids’ removal: in the middle of the night, without paperwork, knowing the next day was Saturday and courts would be closed until Monday.

Josh Sabey and Sarah Perkins are now part of a terrible club of which no one wants to be a member: innocent parents who’ve found themselves in the crosshairs of child protective services.

The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution guarantees people “the right to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures[.]” The Fourteenth Amendment guarantees due process.

As out of his mind with worry as Josh Sabey must have been the night DCF took his kids, he got the law right that night: What DCF did was unconstitutional. Absent a warrant or a plausible imminent threat—which did not exist in the Sabey case—the government cannot come to your home and demand you hand over your children.

A Family Rallies Together

EVERY PARENT KNOWS what it feels like to lose sight of your child for a moment in a public place.

“Like, you’re in the grocery store, and you turn around and your kid’s not there,” Josh says. “And you’re frantically looking for them.”

That’s what Josh and Sarah felt the second DCF drove away with their kids.

“It was like, ‘We need to make calls, but we can’t call the police department,’” Josh remembers.

They began messaging family members instead. They stayed up all night. By morning, an extended network of Sabey-Perkins relatives—from siblings in California to an aunt in France—was in a flurry of activity.

Source: Sabey-Perkins family

Brian, Josh’s eldest brother, remembers being in shock. He went down to his study as soon as he got Sarah’s message and stayed awake all night at his computer, trying to contact newspapers and forums in Massachusetts.

I can’t believe this is happening, David, another of Josh’s brothers, texted. He started researching organizations that might be able to help bring the boys home.

Dia, Brian’s wife, ordered a fire extinguisher in the early morning hours for Josh and Sarah’s home, convinced that if the family made the home as safe as possible, DCF would have to return the boys. She also started calling DCF’s emergency hotline early Saturday morning.

Emphasized they’re putting Clarence’s life in danger by placing him with people who don’t have allergen training, she messaged the family.

Heather, Sarah’s sister, started contacting people to provide character witness statements. She eventually collected 74 pages of testimonials about Josh and Sarah’s parenting. “I can honestly say if I grew up with parents like Josh and Sarah, I would be a better person myself,” one testimonial from a friend read.

“I think there is a misunderstanding,” Clarence’s Sunday School teacher wrote, calling Josh and Sarah “wonderful parents.”

Emily, Josh’s sister-in-law, researched how the family could get Josh’s parents, Lisa and Mark, approved to take temporary custody of Clarence and Cal. The family worked to fast-track Lisa and Mark’s background checks and get them set up in a friend’s home, since Lisa and Mark were visiting from out of state.

Meanwhile, Josh’s brother Daniel and his sister Rachel just started driving toward Massachusetts, wanting to be with Josh and Sarah.

The Lawsuit

PACIFIC LEGAL FOUNDATION is representing Josh and Sarah in a lawsuit against the City of Waltham and the officers who took Clarence and Cal.

The boys were in foster care for less than a day before the Sabey-Perkins family got Josh’s parents approved for temporary custody. Clarence and Cal lived with their grandparents for a month while Josh and Sarah, desperate to get their kids back, worked with attorneys, agreed to DCF demands, wrote their children letters, and had supervised visits. Finally, after a hearing, Josh and Sarah were allowed to take their kids home—but it wasn’t until a second hearing three months later that Josh and Sarah regained full custody of their children.

They weren’t broken by what the government did to them— in a way, they’re closer to each other, and stronger, than they were before.

Once they were in court before a judge, the state’s lack of evidence against Josh and Sarah became painfully clear.

The family still isn’t positive what caused Cal’s rib injury, but Josh’s mom is pretty sure it happened when she was babysitting a few weeks before the ER visit. She was putting Cal in his car seat when he started to slip, so she made a grab for him and he cried out. It happened in a split second, and then Cal quieted. It’s the kind of accident that happens when you have small kids. She didn’t think much of it at the time. She didn’t even mention it to Josh and Sarah— not until long after, when she realized, with horror, that she may have unwittingly set the whole nightmare in motion.

“I just felt sick to my stomach,” Lisa says. “The rib injury was minor compared to the trauma and the harm of everything else that happened.”

Josh and Sarah’s legal case is still active as of this writing. But the family has found its own resolution. They weren’t broken by what the government did to them—in a way, they’re closer to each other, and stronger, than they were before.

Lisa says that the month she spent taking care of her grandsons gave her a special connection to them.

“There will be a feeling toward those two boys the rest of my life that will never be equaled,” she says.

For Christmas, Josh and Sarah made a children’s book for the family. The book tells the story of a mastodon—Clarence’s favorite animal—who gets separated from his family. The mastodon’s “parents, and his grandparents, and his aunts and uncles did not sleep,” the book reads. “They were walking and running and searching everywhere to find him.”

The first page of the book carries an inscription from Josh and Sarah.

“Dedicated to our herd,” they write, “the year our boys were lost, and found, and rescued. Thank you forever.” ♦

Watch 72 Hours, PLF’s short documentary about Josh and Sarah’s case.

A Biased Court Destroyed Families in Colonial Salem

Daniel Woislaw

Attorney

Nicole Yeatman

editorial director

IMAGINE YOU ARE A YOUNG CHILD living in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1692.

You are brought into a crowded meetinghouse where two magistrates—both commanding older men who serve on the council of Massachusetts Bay Colony—are waiting to interrogate you in front of an angry audience. In the room is a loud group of teenage girls who say you and your mother are witches.

You are terrified. You haven’t done anything wrong, but everyone is acting like you did. Your accusers say they’ve seen your ghostly specter tormenting them. The magistrates say they already know your mother is a witch.

You’re just a child. You don’t know what to do— so you give the magistrates what they want. You confess. You tell them your mother made you a witch.

Your mother will insist she’s innocent, but it doesn’t matter. The court will use your words against her. She will die by hanging.

Presumption of Guilt

OF THE 144 PEOPLE prosecuted at the Salem Witch Trials, eight were children under the age of 12. All eight confessed to being witches and implicated their family members.

This was part of the horror that unfolded at Salem over the course of 1692. Neighbors turned against neighbors; husbands testified against wives; scared children pointed fingers at their mothers.

The youngest convicted child, Dorcas Good, was only four or five years old. She was pressured into speaking out against her mother, Sarah Good, who pled innocent. At the pre-trial examination, conducted in public before the accusers, magistrate John Hathorne hammered Sarah with questions that presumed her guilt.

“Why do you hurt these children?” Hathorne asked, referring to the teenage accusers. “What evil spirit have you familiarity with?”

The way Hathorne spoke to the accused is similar to the way police today are taught to speak in interrogation rooms. The Reid Technique, a leading method of interrogation developed in the 1950s, explicitly instructs police to ask leading questions that presume guilt. “A deceptive suspect is not likely to offer admissions against his self-interest unless he is convinced that the investigator is sure of his guilt,” one textbook says. “Therefore, an accusatory statement such as ‘Joe, there is absolutely no doubt that you were the person who started the fire’ is necessary to display this level of confidence.” This is essentially what Salem magistrates were doing, centuries before it was an established police technique.

But there are two differences between modern police interrogations and the pre-trial examinations of the Salem Witch Trials.

First: The Salem examinations were conducted in public. Accusers were present and often descended into “fits” when near the accused, which was seen as evidence of the accused’s guilt. These examinations were supposed to allow magistrates to decide whether the accused should be held in jail for a future trial. There was no reason or requirement that they be conducted in public; in fact, 17th-century legal authorities specifically recommended examinations be conducted in private. But for unknown reasons, the Salem magistrates chose to interrogate accused witches before an audience, including accusers and family members.

Second, and more importantly: Several of the magistrates leading the examinations soon became judges on the special court created to try the accused witches.

And in its short five months of existence, the court didn’t find a single accused witch “not guilty.”

A Special Court

SIR WILLIAM PHIPS, the new governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony, didn’t exactly have a great mind for the law.

Phips was a fortune hunter. He didn’t learn to read or write until he was an adult, and even then, he never did it well. Born in Maine, he’d traveled to London in the 1680s to convince the king to fund his treasure-hunting mission to the Caribbean. When Phips stumbled onto treasure, King George II was so pleased, he gave Phips a knighthood. In 1692—just before Salem magistrates started filling jail cells with accused witches—Phips successfully lobbied the king to become the first royal governor of the newly chartered Massachusetts colony.

By the time Governor Phips returned to Massachusetts in May 1692, the colony was fully in the grips of witch paranoia. Magistrates were conducting public examinations of accused witches and holding more and more “witches” in jail for trial.

The crowded jails were now Governor Phips’ problem to solve.

Phips decided to create a special court to try the witches: the Court of Oyer and Terminer. Phips appointed nine judges to the court. All nine judges were members of the colony council and prominent men whom Phips knew. Several were magistrates who’d been leading the examinations of accused witches. One was Phips’ own lieutenant governor.

“[T]he court, in my opinion, was illegally appointed as an emergency act,” Massachusetts attorney Frank Grinnell wrote centuries later in 1975, after the Massachusetts legislature voted to formally exonerate men and women condemned to death by the Court of Oyer and Terminer.

Only the legislature was empowered by the charter to create courts, Grinnell explained, not the governor. But Phips “got rattled like all the rest,” Grinnell wrote, “and he appointed a group called a court which, being also ‘rattled,’ made a mess. The whole business was illegal…”

If accused witches waiting in Salem’s jail were hoping to be tried in a fair court of law, where sanity would finally return to Salem, they would be brutally disappointed.

Given the judges Phips appointed, the court could hardly be unbiased. Judge John Hathorne had led most of the examinations and was clearly already convinced of each accused witch’s guilt. In one infamous examination exchange—which inspired a scene in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible—accused witch Bridget Bishop tried to tell Hathorne she was innocent, pleading that she didn’t even know what a witch was. Hathorne pounced. “How can you know you are no witch,” he demanded, “and yet not know what a witch is?”

If accused witches waiting in Salem’s jail were hoping to be tried in a fair court of law, where sanity would finally return to Salem, they would be brutally disappointed.

With Ghosts as Witnesses

THE FIRST TRIAL took place on June 2, 1692. It was a travesty.

The Court of Oyer and Terminer accepted “spectral evidence”—eyewitness testimony about acts committed by someone’s specter or spirit—as reason enough to convict. It was impossible for anyone to defend themselves or their family members against spectral claims. Proving you were physically at home, nowhere near the accuser, wouldn’t help. A husband couldn’t provide an alibi for his wife. The accused’s loved ones were helpless.

Even by the standards of 1692, the Court of Oyer and Terminer’s use of spectral evidence was radical. Theologians at the time argued spectral evidence could be used as a clue to determine guilt but not as the basis for a legal conviction.

Source: Peabody Essex Museum

In its zeal to convict accused witches, the Court of Oyer and Terminer was apparently forming its own rules.

The court also refused to give the accused an opportunity to cross-examine witnesses, or to allow them to review evidence ahead of trial. The judges also freely allowed hearsay and prior conflicts to be introduced as evidence.

The proceeding was not designed for justice. It was designed to find people guilty.

Bridget Bishop was the first accused witch to be tried. She was hanged a week after her trial. The Court of Oyer and Terminer oversaw her execution. After executions, the sheriff would often confiscate the property of the executed—a violation of usual colonial practice, and a throwback to the Old World justice of England, where property forfeiture for felonies was common practice. In Salem, the sheriff even took personal effects. After George Jacobs was convicted of witchcraft and executed, according to historical records, the sheriff visited Goodwife Jacobs and demanded she hand over “even her Wedding ring.”

Families of Salem

THE SALEM WITCH TRIALS tore families apart. Puritan New England was a family-focused society. Even in court documents, people were identified as “son of” and “wife of” to emphasize their connections. This should have been Salem’s strength.

But with the Court of Oyer and Terminer treating all accused witches as if they were guilty beyond a doubt, family ties became an awful binding—an extension of guilt in the eyes of the court.

Sarah and Thomas Carrier were seven and ten years old, respectively, in 1692. When their mother was put on trial, the magistrates brought Sarah and Thomas in for an examination. Under pressure, Thomas confessed that “his Mother taught him witchcraft.” The Court of Oyer and Terminer hanged Goodwife Carrier a week later.

Eighty-year-old Giles Corey testified against his wife, Martha Corey, then seemed to regret it. When Martha was first accused, Giles told magistrates that one evening at home, he felt as if he couldn’t pray. He wondered if his wife had stopped him from praying somehow. Meanwhile, the magistrates tried and failed to get Martha to confess during examination. “You are now in the hands of Authority,” John Hathorne told her. “Tell me now why you hurt these persons.”

Giles stopped cooperating with the government’s case against his wife and quickly found himself accused alongside Martha. His story—which was also fictionalized in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible and Henry Longfellow’s Giles Corey of Salem Farms—is remembered for what happened next: Convinced the Court of Oyer and Terminer had already decided he was guilty, Giles refused to enter a plea at his trial. This was in September of 1692, in the court’s fourth month. Giles had seen innocent neighbors found guilty and executed. He’d seen the sheriff confiscate people’s property, leaving nothing of their estate for family members.

He would not submit himself to the court’s dubious authority. “I will not plead,” his character says in Giles Corey of Salem Farms.

If I deny, I am condemned already, In courts where ghosts appear as witnesses, And swear men’s lives away. If I confess, Then I confess a lie…

The court marked Giles as “standing mute” and ordered him subjected to peine forte et dure—heavy stones piled on his body. It was the only time an American court ever gave that order.

Giles had seen innocent neighbors found guilty and executed. He’d seen the sheriff confiscate people’s property, leaving nothing of their estate for family members.

On September 18, 1692, in a field by the jail, Giles Corey was pressed to death by stones. His last recorded words were a request: “More weight.”

It’s unclear whether the court intended for Giles to die, historian Richard B. Trask writes in Legal Procedures Used During the Salem Witch Trials. But, Trask says,

[w]hether the torture was meant to get Corey to agree to trial or was a de facto execution, the old man died under this torture, giving a silent though profound statement of his contempt for the justice of this “hanging” court.

Afterward, unlike what happened with the estates of other executed men, Giles’ estate was not seized by the sheriff. There is debate about whether that’s because Giles refused to plead or whether it’s because Giles’s gruesome death shook some sense into Salem’s authorities.

Either way, Giles’s sons were allowed to inherit the family farms. And Giles’s death turned Salem against the Court of Oyer and Terminer.

The Backlash

BY OCTOBER, the court had gotten confessions from 58 people and hanged 19—14 of them women. Several more women and infants had died in prison.

A few prominent men—including a Boston merchant and the president of Harvard College—were starting to complain about the Court of Oyer and Terminer’s proofs and procedures. One councilman wrote to another that he worried the “lives of innocent persons are alike in danger” at the court. Another man wrote that he didn’t intend to “cast dirt on authority” but that the methods of the court worried him. Jailed “witches” were writing the governor, begging to be tried in Boston rather than at the Court of Oyer and Terminer. A Boston reverend published an anonymous letter arguing that in a just court, “there shall be good and clear proof against the criminal” because not only was the person’s life on the line, but also “a ruinous reproach upon his family.”

Increase Mather, the Harvard president, gave an October sermon where he carefully criticized the court’s procedures while praising the intent of the judges, many of whom were his friends. Bernard Rosenthal writes in Salem Story:

Mather, while deploring the judicial proceedings, was reluctant to attack the distinguished judiciary conducting them. These were his friends and professional associates, with him among the most powerful people in the colony. None of Mather’s comments, no matter how damning, ever faults the individuals who implemented the proceedings. He had the untenable task of faulting the process while asserting the wisdom of those who conducted it. Indeed, when the witch trials ended, he damned the prosecution and justified the prosecutors.

Still, Mather’s critique struck a chord in Boston. “It were better that Ten Suspected Witches should escape,” said Mather in his sermon, “than that one Innocent Person should be Condemned.”

On October 29, in response to rising criticism, Governor Phips shut down the Court of Oyer and Terminer. He eventually pardoned all the remaining accused witches and freed them from jail. The governor even tried to distance himself from what his judges had done, claiming he’d been away fighting American Indian tribes most of the time the court was in session. Historical records show Phips was lying: He regularly met with judges while they presided over the trials.

In 1711, the Massachusetts legislature voted to compensate accused witches who’d survived the trials and the descendants of those who’d been executed. The trials had quickly become a source of shame for colonists, who recognized the Court of Oyer and Terminer had dealt irreparable harm to some New England families.

Some who’d been involved in the trials, like Phips, tried to erase the episode from history. The Court of Oyer and Terminer’s records are gone. Historians have detailed transcripts from the pre-trial examinations, but not the court’s trial records—presumably because someone involved in the proceeding destroyed them.

Descendents of accused witches were vindicated; meanwhile, the descendants of judges who served on the Court of Oyer and Terminer wrestled with shame. One judge, Waitstill Winthrop, wrote regular letters to family members throughout his life. When his descendants donated his letter archives to a historical society, letters from the year 1692 were mysteriously missing. Historians believe the Winthrops destroyed them, disturbed by their family’s role on the Court of Oyer and Terminer.

Two judges, Samuel Sewall and John Hathorne, behaved in polar opposite ways after the trials. Sewall publicly confessed that he regretted his role in the trials; for that, he became well-respected in the colony. Sewall’s descendants today can see a mural of him apologizing in the Massachusetts House of Representatives in a series titled, “Milestones on the Road to Freedom in Massachusetts.”

Hathorne, on the other hand, never apologized for his role as a judge on the Court of Oyer and Terminer. His descendants were so ashamed of him that his great-great grandson, the writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, added the “w” to his name to distance himself from the family legacy.

Salem’s Legacy Today

THE SALEM WITCH TRIALS took place almost a century before the Constitution was written. The backlash helped colonial Americans to shape the principles of modern jurisprudence and procedural protections, shifting the burden of proof so that courts could no longer presume the accused was guilty. Today our legal rights include the right to review evidence, to cross-examine witnesses, to exclude hearsay, and to be tried by a fair judge and impartial jury. These are all protections that would have prevented the Salem Witch Trials.

“The trials are filled with cautionary tales about how catastrophically bad things can go when legal proceedings fail to offer certain minimum guarantees,” Len Niehoff, law professor at the University of Michigan, says.

Shockingly, over three centuries after the Salem Witch Trials, there is still one corner of the American court system that doesn’t offer certain minimum guarantees—where the accused is still presumed guilty.

The in-house courts of administrative agencies do not operate like post-Constitution courts. Like the Court of Oyer and Terminer, these courts—at the Consumer Product Safety Commission, Securities and Exchange Commission, and other agencies—are biased against the accused. The judges are not impartial; they’re employees of the prosecuting agency. People in the crosshairs of an agency adjudication are forced to prove their innocence—to show that their speech isn’t dangerous, or that their new product is safe, or that their land isn’t on a federally protected wetland. The deck is stacked against them.

Pacific Legal Foundation has launched an initiative to end unjust agency adjudication. In one case, PLF attorneys are representing an Oklahoma family, the Leaches, against the Consumer Product Safety Commission. The Leaches have been in business since the 1980s selling baby products. The CPSC says one of the family company’s products is unsafe because parents might misuse it. The agency has dragged the Leaches into an in-house proceeding in which they’re treated as guilty. The proceeding could destroy their family’s legacy.

“I wouldn’t wish this on anyone under any circumstance, ever,” Jamie Leach says.

For her, fighting the unfair “court” procedures at the CPSC isn’t about winning or losing. “It’s being able to experience justice,” she says.

That’s what every American deserves: the right to a fair trial in a true court of law, with full procedural protections—not to be dragged before a biased “court” that has already decided you’re guilty. ♦

Racial Quotas for City Contractors May Ruin This Family Business

Erin Wilcox

attorney

IN THE MID-NINETIES, Jerry Thompson was headhunted for a Texas company that paid good money. He was a whiz at sales. So he moved his wife, Theresa, and two kids from Michigan to Texas.

He loved living in Texas. But two years in, he couldn’t stand his job.

Why’d you hire me if you’re not going to let me make decisions? he thought.

When he told Theresa he wanted to try working for himself for a change, she supported him. Jerry and Theresa are high school sweethearts. “I love her to death,” he says.

Of all contractors who submitted a bid, the Thompsons scored highest in every single category—except “Minority, Women, Disadvantaged Enterprise,” in which they scored zero.

They put everything they had into a commercial landscaping business. “First year was not fun,” Jerry remembers. “I thought I was going to go out of business.” Then he landed a couple good contracts. “Haven’t looked back ever since,” he says. He thinks more people should take the risk of striking out on their own as a family business. “It’s been good for us and our family,” he says.

Today Jerry and Theresa own two companies in Houston: Landscape Consultants and Metropolitan Landscape Management. Their two kids—a son and a daughter—“now pretty much run the business,” Jerry says proudly. “I just get us into trouble—like this thing.”

By “thing,” Jerry means the lawsuit.

When Being Good Isn’t Good Enough

MOST OF THE THOMPSONS’ landscaping work is for the government: They have contracts with the City of Houston, Houston’s Midtown Management District, and nearby cities and counties. Their companies do irrigation installation, flood control, tree planting, and routine maintenance, including for schools.

But lately it’s been tougher to win and manage government contracts.

Since 1984, Houston has been setting aside a percentage of its contracts for minority-owned businesses. In the past couple of years, nearby cities and counties have followed Houston’s lead, meaning that more and more jobs in the Houston area come with stipulations about race.

The Thompsons are white. That can make things difficult.

In 2022, the Thompsons bid on a field maintenance job for Midtown Management District. The district evaluates contractors on a point scale: You can score up to 50 points on financial considerations, 25 points on organizational qualifications and references, 15 points on your proposed approach to the job, and 10 points on being a certified “Minority, Women, Disadvantaged Enterprise.”

Of all contractors who submitted a bid, the Thompsons scored highest in every single category—except Minority, Women, Disadvantaged Enterprise, in which they scored zero.

They didn’t win the contract.

The winning contractor scored a total of 87.68 points, including 10 points in the Minority, Women, Disadvantaged Enterprise category. The Thompsons came in second highest with 84.98.

In other words, the Thompsons lost to a company with a worse bid in every way—by the district’s own standards—because of the color of their skin.

“And the sad part about that is we had that contract on and off for 15 years,” Jerry says, “so they knew we were good.”

Twisted Incentives

LAST YEAR the Thompsons thought about selling the business.

It’s not just the contracts they lose that bother Jerry; it’s also what they have to agree to these days to win.

For their five-year contract with the City of Houston, the family must agree to subcontract 11% of the job to certified minority business enterprises (MBEs). It’s a $1.3 million contract—so the Thompsons are forced to divert at least $143,000 of work away from their (largely minority) staff, whom they trust, to unnecessary subcontractors.

The Thompsons don’t like managing subcontractors. As a family business, they run a tight operation: 45 employees, mostly working out of their homes, without a lot of overhead or waste. That’s actually typical of family-run businesses: According to Harvard Business Review, family businesses are more frugal, carry little debt, and retain good talent better than their competitors do. “[T]hese practices come more naturally to executives who feel an obligation to be stewards for the next generation,” the publication explains.

It’s not easy for a family business with tight margins and high standards to give away a tenth of their work to subcontractors.

“If we have to give up 10% or 15% or 20% of that contract to someone we don’t really know and trust—I mean, who’s responsible for that contract at the end of the day?” Jerry asks. When subcontracting, the Thompsons have to manage subcontractors’ liability insurance issues; they have to be comfortable with subcontractors at sensitive jobs, like schools, where “your people have to be good people.” To fulfill the subcontractor requirement, the Thompsons have to choose from a list of government-certified minority business enterprises. “How do I know who they are?” Jerry says.

Imagine leaving your adult children to navigate a twisted incentive system where the family business would be shown government favoritism under one child—the child who’s not actually interested in running the business—but not the other.

So yes, it occurred to Jerry that it might be time to sell the business and move on.

“But my kids are involved in it,” Jerry says, “and my son doesn’t want to sell it.”

Jerry’s daughter is less emotionally attached to the business. It’s given her a good job, but she’d be okay if the family had to sell. It’s Jerry’s son who really loves the business—who talks about growing it and puts his foot down when anyone starts talking about selling.

Ironically, if the family restructured the whole business to give Jerry’s daughter majority ownership and had her take over most of the daily decision-making responsibilities, she could probably get certified as a woman-owned business enterprise. The business would suddenly be treated differently by the government.

Imagine leaving your adult children to navigate a twisted incentive system where the family business would be shown government favoritism under one child—the child who’s not actually interested in running the business—but not the other.

Working for Each Other

EDELMAN’S TRUST BAROMETER, an annual report tracking trust in institutions, ranks family-run businesses as the most trusted type of enterprise—above public companies and far above government.

“I come from a family business,” Karen Mills, former administrator of the Small Business Administration, told C-SPAN in an interview about the future of American small businesses. Karen’s grandfather was an immigrant who started a textile company from the back of a shoe shop. Karen worked for him growing up. “He used to say, ‘Our family doesn’t work for other people. They work for themselves,’” Karen remembers.

Source: Getty

In other words, family business owners work for each other—for the good of the family, across generations. That’s precisely what makes customers trust family businesses. In a time of widespread distrust for capitalism, with some Americans worried that self-interest has atomized society, family businesses are a kind of salve. Studies show family businesses tend to invest in their communities, to preserve workplace values, to care about their reputations, to perform well in crises, and to prioritize long-term success over short-term rewards. At a family business, self-interest is inherently family-interest.

Jerry wants to protect his kids’ future. He used to be confident that as long as their landscaping business provided the best work for the lowest price, they’d be successful. Now he’s less confident. Race-based set-asides have changed the game. They’re affecting more and more of the Thompsons’ business.

“It’s hitting harder, it’s hitting closer,” Jerry says. “It’s starting to surround us.”

On a purely economic level, the racial set-asides are bad enough. “Anytime you do business with a government entity, the money comes from the taxpayers,” Jerry says. “So [the government] should be more protective of every dollar. I mean, I think we all agree with that.” Local governments are now rejecting the lowest bids from highly qualified contractors and allowing themselves to be up-charged solely in the name of diversity, equity, and inclusion. “They’re spending other people’s money, public money, tax money, to fulfill some kind of a goal they think they need to do,” Jerry says.

But it’s not just tax dollars at stake. Legally—and morally—it’s also fundamentally wrong for the government to take money out of one business’s pocket and give it to another because of the business owners’ respective races. It violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution.

After Jerry stumbled onto a Pacific Legal Foundation blog post about Houston-area racial set-asides, he reached out to PLF. He wasn’t sure he wanted to actually pursue a lawsuit. The rest of his family definitely wasn’t sure. His kids were worried that fighting the MBE program would draw blowback in the community. They care about the business’s reputation.

But after Jerry started talking to PLF, he and his family decided to sue the City of Houston and Midtown Management District.

Legally—and morally—it’s also fundamentally wrong for the government to take money out of one business’s pocket and give it to another because of the business owners’ respective races.

“I can just see this thing destroying our business if we don’t at least try,” Jerry says. He and Theresa have three grandchildren now. He’s thinking about what his grandchildren will be left with.

Most businesses aren’t going to speak out against the racial set-asides, Jerry says, even if they’re crushed by them.

“Because we can’t afford to take on City Hall,” he explains. “That’s why this PLF thing intrigues me. Because they’ll just get away with it otherwise.” ♦

When Government Gets Between a Mother and a Midwife

Brittany Hunter

editorial writer

Joshua Polk

attorney

THE BIRTH OF A CHILD is a sacred experience in a mother’s life. How and where she chooses to bring her baby into the world is a deeply personal decision that should be free from government interference.

Yet in some states, certificate-of-need (CON) laws stand between mothers and their freedom to choose where they give birth.

A Birth Center in Georgia

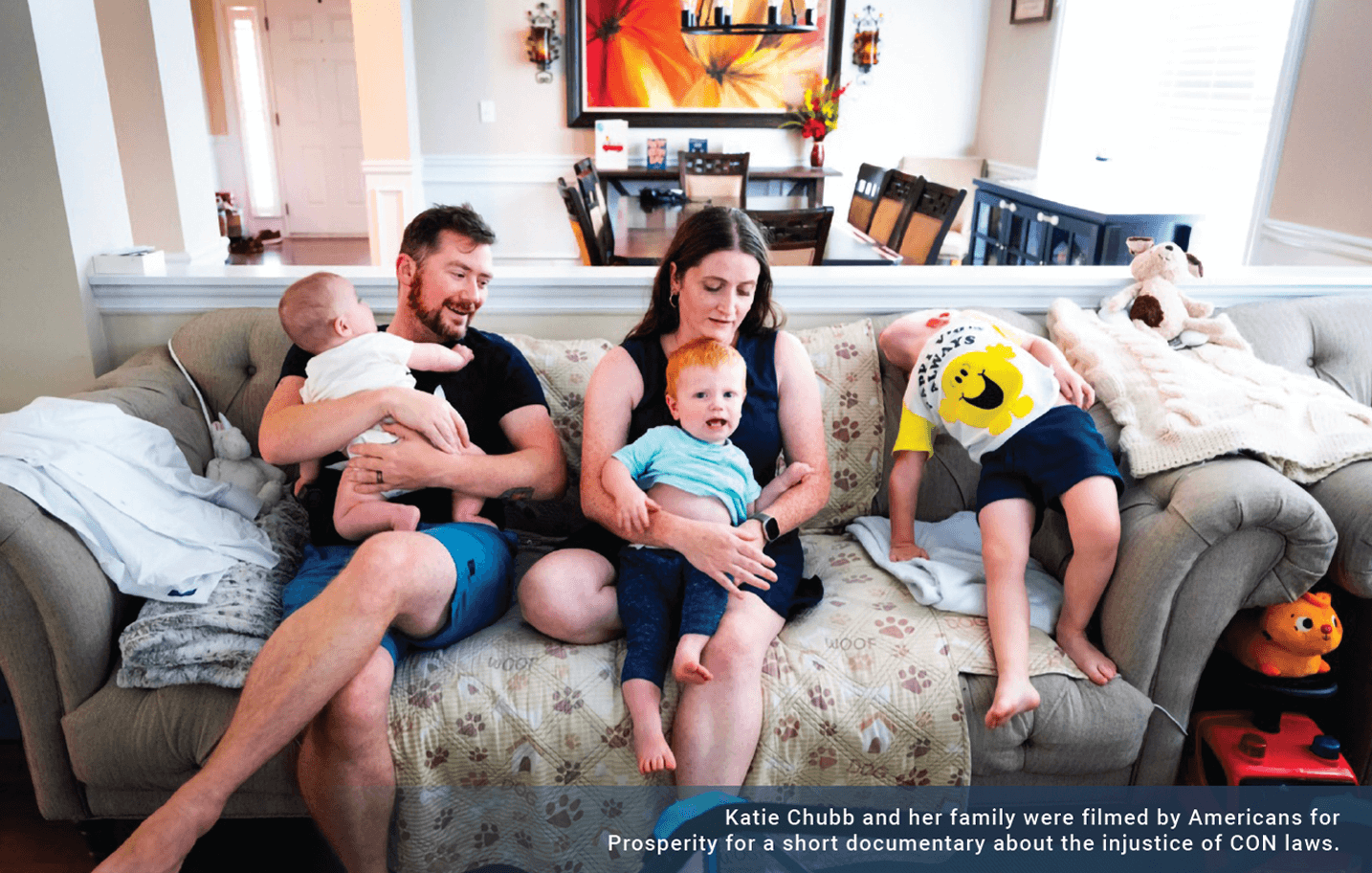

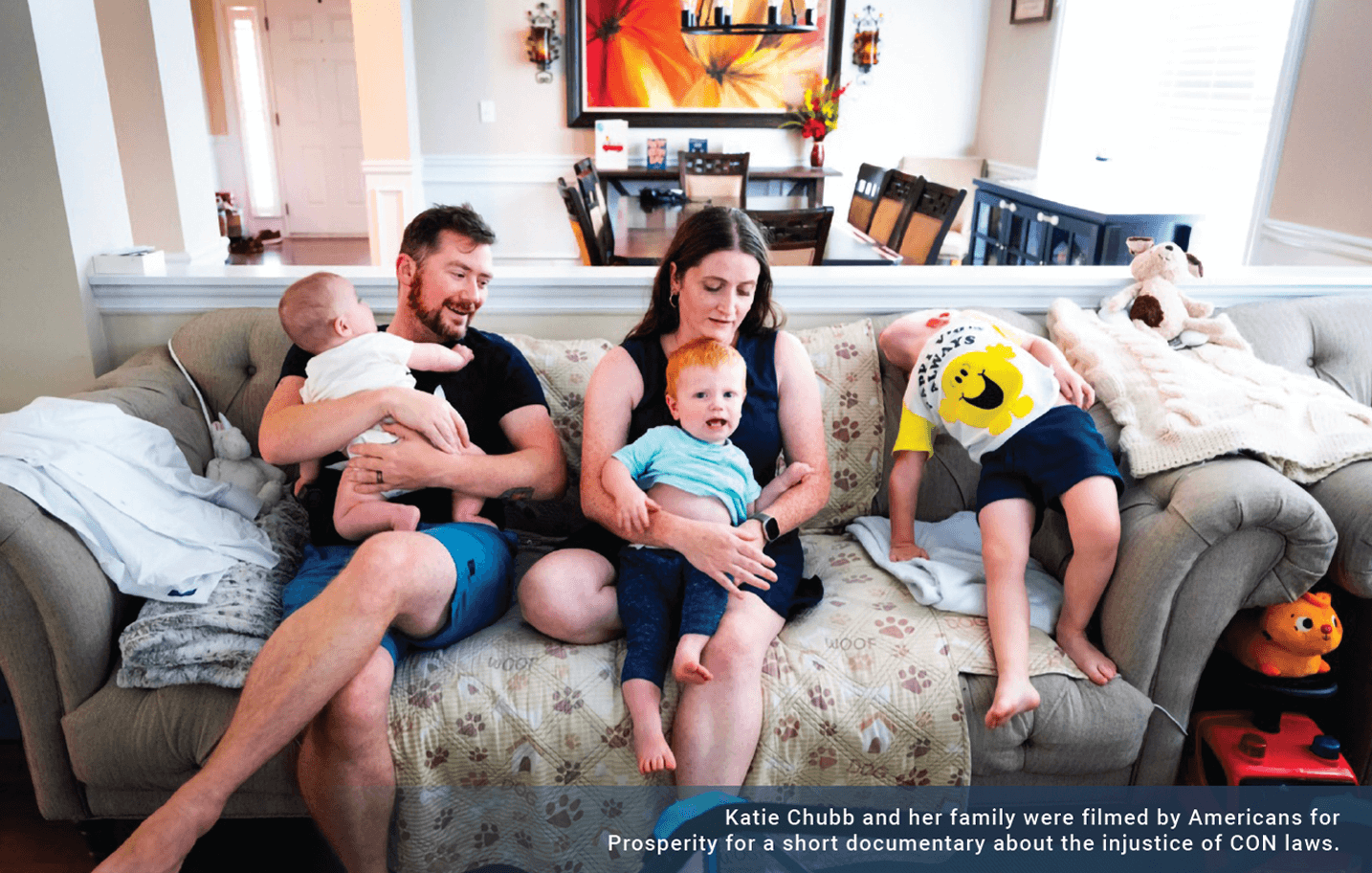

KATIE CHUBB and her husband Nick drove nearly three hours from Augusta, Georgia, to deliver their baby at the Atlanta Birth Center. Taking a road trip is the last thing a mother in labor wants to do. But Katie had her mind set on having her baby in a birth center, and there weren’t any options closer to home.

Katie is from the United Kingdom, where midwifery is a common practice. When she was pregnant for the first time, she and Nick weighed whether to go with a midwife or an obstetrician. They met with an OB at their local hospital, but the appointment left them disappointed.

“They separated Nick and I into different rooms,” Katie remembers. “They told me information I already knew.”

The Atlanta Birth Center, on the other hand, blew Katie away. “It was like no other care I had ever received,” she remembers.

When I went to the birth center, they’re like, “Okay, what do you know about your pregnancy? How educated are you? What do you want to know going forward? What can we help you with? What resources can we connect you with?” It was completely different.

Nick was also impressed. “I thought, ‘This is significantly better for the family. Not just for the mother, but for the family,’” he said.

How the Government Standardizes Childbirth

TODAY, 99 PERCENT of American women give birth in a hospital, according to Lauren Hall’s The Medicalization of Birth and Death.

Hall writes:

Almost 40 percent of those women will be induced, over one-third will have a cesarean section, and many more will have forceps deliveries, episiotomies, labor augmentation, or other interventions. These intervention rates are much higher than those in comparable developed countries. Despite the high rates of interventions, and in part because of them, maternal mortality has actually risen in the past decade[.]

Birth wasn’t always like this in America. But starting in the 1910s and ’20s, state governments began to pass regulations aimed at standardizing medical care. Then, in 1946, President Harry Truman passed the Hill-Burton Act, which injected federal money into hospital systems.

“And in order to do that, they actually create these blueprints of what these hospitals should look like,” Hall says. “And those blueprints end up really calcifying maternity care… As the hospitals get standardized, patients get standardized, too.”

Delivery wards became almost like factories designed to treat expectant mothers as quickly and efficiently as possible. When doctors see dozens of patients each day in a hospital, they’re often forced to resort to a “one size fits all” model that uses medical intervention for everybody. That’s not a problem for the majority of women. But some are desperate for a less “factory”-like experience.

Source: AFP

Midwives, on the other hand, tend to be more personal and flexible: They’re more likely to follow mothers’ lead and less likely to insist on medical interventions unless necessary. They’re also more likely to have a continued relationship with families post-partum. That’s what a lot of women want.

As Nick puts it, “A doctor will say, ‘I’m delivering this baby.’ The midwifery way is to say: ‘You are going to be having this baby.’ The midwife is there to make sure you are okay and to assist in the process.”

Midwives in Iowa

CAITLIN HAINLEY had her first child in China when she and her husband were living abroad. She labored for a long time, then had an emergency C-section. When she got pregnant again, she wanted the option of having a vaginal birth, which many doctors will not allow if a mother has previously had a C-section.

Her family moved back to the United States late in her pregnancy, thinking they would have more birthing options. In a shocking turn of events, Caitlin learned that she would have had more choices had she stayed in China. The American hospital she went to insisted that she have another C-section.

Caitlin decided to use a midwife instead. Caitlin recalls how the midwives’ faith in her ability to deliver without needing major surgery made her feel supported. She had the freedom to choose what was best for her and her baby. She gave birth to a healthy baby without needing a C-section.

Caitlin eventually went to school to get her nursing degree, then became a midwife. She and her husband struggled financially during her pregnancies, and most midwives don’t take insurance, which made things hard for Caitlin’s family. She wanted things to be better for women in her home state, Iowa. So she and another midwife, Emily Zambrano-Andrews, started the Des Moines Midwife Collective, the first homebirth service to accept insurance.

Both women love what they do and consider it a great privilege to assist and support expectant mothers. Their midwife service gives mothers the freedom to choose how they want to give birth while significantly lessening the financial burden.

The only problem is that legally, Caitlin and Emily can’t have an office. They only can visit patients in their homes. Emily and Caitlin dreamed of opening a freestanding birth center where mothers could come to deliver their babies.

But Iowa’s certificate-of-need laws have prevented them from opening their birth center.

Certificate-of-Need Laws

CERTIFICATE-OF-NEED LAWS are a state-level problem—but like a lot of state problems, they started with the federal government.

In 1974, Congress passed the National Health Planning and Resources Development Act, which created financial incentives for states to develop new regulatory processes for health-related services— including CON laws.

CON laws force new businesses to prove there’s a community need for their services. In states with these laws, competing businesses—in this case, hospitals—are given an opportunity to quash a new service’s application for a certificate of need.

These laws do not help patients. A 2016 Mercatus Center study found that hospitals in CON states perform worse than those in non-CON states. Even the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice have argued for the repeal of CON laws, noting that while the laws had “laudable goals… it is now apparent that CON laws can prevent the efficient functioning of health care markets[.]”

Iowa is a CON law state. Iowa allows midwives to assist in homebirths without issue. But if a midwife wants to open a freestanding birth center offering those same services, they must apply for a certificate of need—and before their certificate is approved, competitors will have a chance to argue in a hearing that there’s no need for new birth services.

In Iowa history, there have been only two birth centers that were able to get certificates of need, both of which are now closed.

Iowa is incentivizing makeshift arrangements like “birth bnbs” over permanent birth centers where equipment is kept on site.

Here’s where the Iowa laws get really strange.

After one of the former birth centers closed, the owner kept the building and now uses it as a “birth bnb” where midwives and laboring mothers can come to deliver babies. As long as midwives bring their own supplies and equipment, no certificate of need is needed. The CON laws come into play only if supplies and equipment are kept on the premises. In other words, Iowa is incentivizing makeshift arrangements like “birth bnbs” over permanent birth centers where equipment is kept on site.

Caitlin and Emily now are challenging Iowa’s certificate-of-need law in court, with PLF’s help.

Starting a New Georgia Birth Center

In Georgia, Katie Chubb also is working with PLF to fight certificate-of-need laws.

After her experience with the Atlanta Birth Center, she went home to Augusta and began to wonder: “How hard would it be to start a birth center here?”

Nick loved the idea and was fully onboard. He saw childbirth as a family affair, not something a woman should have to do on her own. What he and Katie envisioned wouldn’t just be a place to give birth—it would be a community of families who were there to support and learn from each other. The Augusta Birth Center would offer a variety of workshops, including classes on CPR, “Daddy Doula” classes, and even a workshop on introducing new babies to family dogs.

Nearly everyone Katie and Nick told about their birth center supported their idea whole-heartedly… except existing hospitals. To get a certificate of need, Katie and Nick needed one of the local hospitals to sign a transfer agreement, stating that the hospital would admit birth center patients in an emergency. But none of the hospitals would sign.

Hospitals are businesses with a near-monopoly on birth. They have every reason to veto competition.

Katie knows there’s a need in Augusta for a birth center. There is currently no birth center within a 130-mile radius, and only one of three local hospitals offers midwifery services. Local nurses have told Katie stories about hospitals not having enough beds and women giving birth in hospital hallways. Georgia has the second-highest maternal mortality rate in the country. In some years, the Augusta-area maternal mortality rate ranks higher than in Cuba or Syria.

These problems aren’t exclusive to Georgia. According to a recent report by the Commonwealth Fund, the United States has the highest infant and maternal mortality rates out of all developed countries—and this is despite spending the most on health care.

The government’s stranglehold on midwifery practices is not helping.

Getting Government Out of the Way

CAITLIN HAS FIVE CHILDREN. Her last two kids she had at home. That’s what most women who don’t want to give birth in a hospital end up doing. But women shouldn’t be forced to choose between a hospital or home.

“I don’t ever want people to feel like they have to have their baby alone because they don’t have access to the type of care they desire,” Caitlin says.

Women have traditionally given birth surrounded by other women—by a support system, including midwives and doulas, who stay with them through the process. That’s what Caitlin and Emily want to provide in Iowa and what Katie Chubb wants to provide in Georgia.

The government should get out of these women’s way.

By preventing midwives from opening birth centers, CON laws are restricting one of the most important and personal choices a woman can make: how to give birth to her child. It’s the very first choice a mother makes in an endless series of parenting choices she’ll make as her child grows older, learns to walk, goes to school, and becomes an adult in the world. This first choice—how to bring her child into the world, whom to trust with her child’s delivery, where she should be when her child takes a first breath and looks around— cannot be redone. It’s a private and personal decision that is not the government’s to make.

Caitlin, Emily, and Katie want to give women more choices for childbirth. CON laws give them fewer. It’s that simple. Some women feel safer and more comfortable when they are working with midwives in a birth center—and they should have the freedom to make that choice for themselves and their families.

Pacific Legal Foundation is representing both Katie’s Augusta Birth Center and Emily and Caitlin’s Des Moines Midwife Collective to fight back against CON laws and protect each mother’s right to give birth as she chooses. ♦

For Some School Boards, Parents Are the Enemy

Jim Manley

state legal policy deputy director

THIS YEAR, CALIFORNIA LEGISLATORS tried to create new criminal penalties for parents who “harass” school board officials or disrupt school board meetings. The legislators drafted a vague bill that defined harassment as two or more acts directed at an education official. Potentially, if you sent two emails that caused a school board member to suffer “substantial emotional distress,” you’d fall under the bill’s definition.

Pacific Legal Foundation and others questioned the bill—but in September, it passed California’s legislature by a wide margin.

Then it got to Governor Gavin Newsom’s desk. The governor refused to sign it.

“[W]e need to be cautious about exacerbating tensions,” Newsom explained as he vetoed the bill. As written, he pointed out, the bill could “be perceived as stifling parents’ voices in the decision-making process.”

“We don’t need more gas on this fire,” he added.

An Equity Agenda

HERE’S WHAT NEWSOM meant by “this fire.”

In recent years, parents across the country have felt increasingly villainized by school boards and education officials.

In some districts, tensions began with the fight to reopen schools during the COVID-19 pandemic. Parents, upset about kids losing months of schooling, were met with largely unsympathetic education officials. An entire school board in Northern California resigned after they were caught complaining about parents “want[ing] their babysitters back.”

“Part of the problem,” a teacher said in a 2021 op-ed for NBC News, “is that parents think they have the right to control teaching and learning because their children are the ones being educated. But it actually (gasp!) doesn’t work that way … It’s sort of like entering a surgical unit thinking you can interfere with an operation simply because the patient is your child.”

On one side are education officials who want to change policies—including admissions, discipline, and grading policies—to make outcomes more level across racial groups. On the other side are parents who don’t want students treated differently according to race.

The big fight between parents and school districts today isn’t about COVID. It’s about equity.

On one side are education officials who want to change policies—including admissions, discipline, and grading policies—to make outcomes more level across racial groups. On the other side are parents who don’t want students treated differently according to race.

“They’re obsessed with equity,” one Virginia mom complained about the Fairfax County School Board in an interview for Pacific Legal Foundation’s short documentary, Fortune in the Book. When the school board replaced Thomas Jefferson High School’s race-blind admissions test with a process aimed at increasing black and Hispanic enrollment, parents were furious: It seemed to signal that officials were prioritizing identity politics over academic merit. Once the top-ranked public high school in the country, the Fairfax County school’s ranking recently dropped to #5.

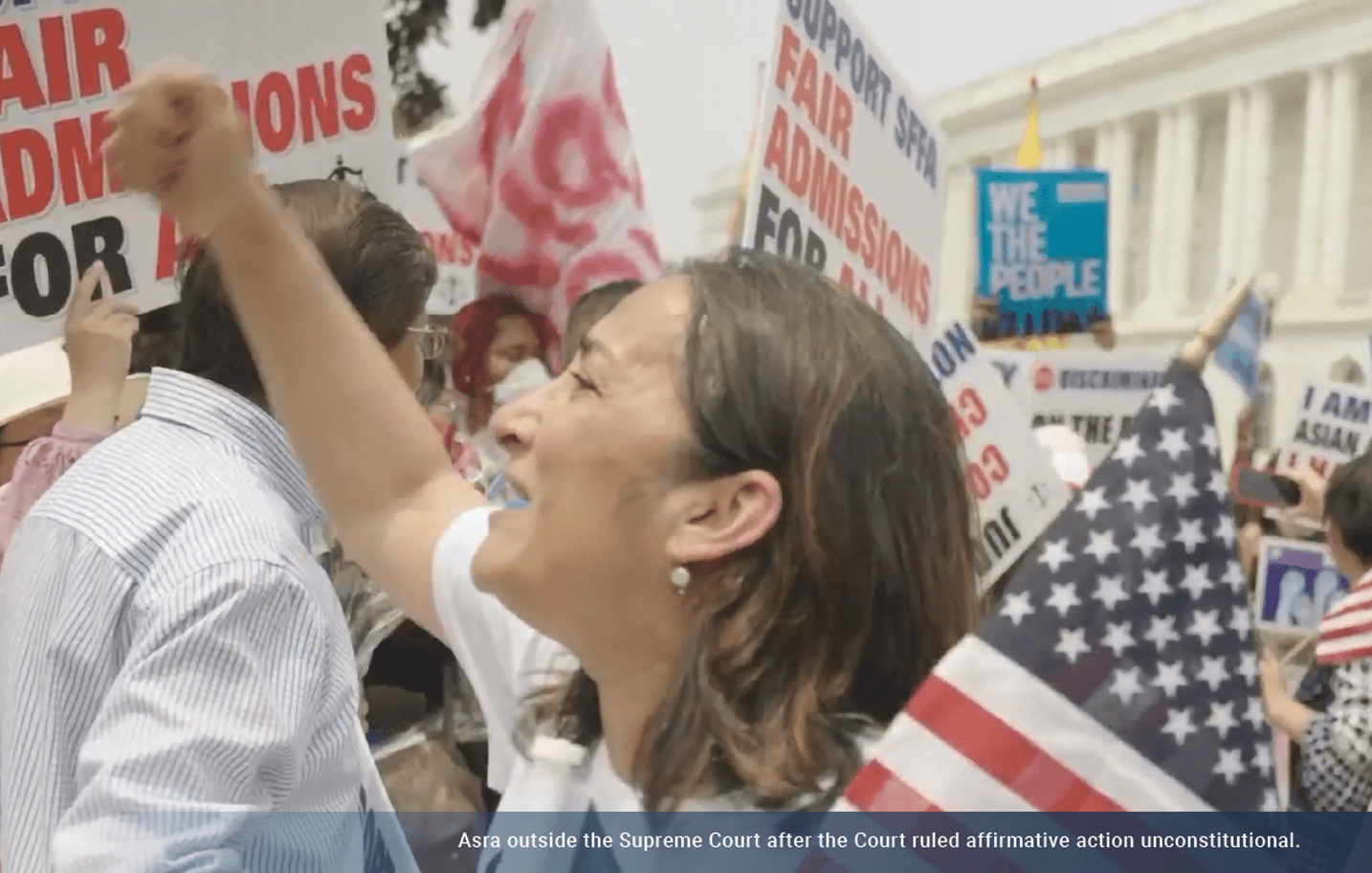

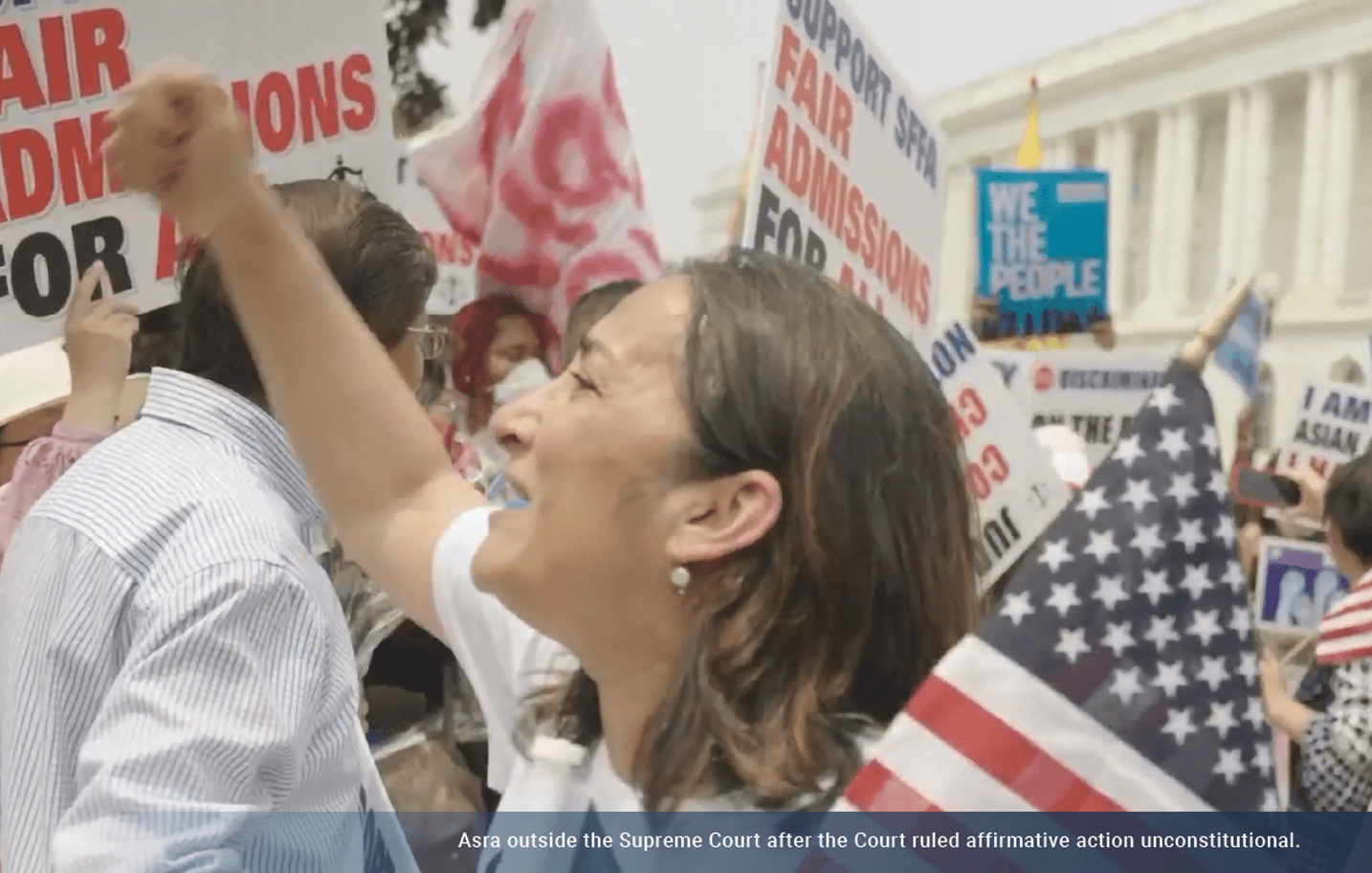

Many parents began attending school board meetings to voice their concern. Some, including Asra Nomani, formed the Coalition for TJ, which sued the school board with PLF’s help. The case is currently on petition to the Supreme Court; if accepted, it will likely be heard in the spring.

Before Fairfax pushed the new admissions changes, Asra considered herself “a good PTSA mom.” But when she objected to the school board’s agenda, she was treated like an enemy. After she gave an impassioned speech at a school board meeting, security personnel made a beeline for her. When PLF interviewed Asra for our documentary, she wore a shirt with bejeweled lettering: “I’m a mom, not a domestic terrorist.” (The shirt was inspired by the National School Boards Association’s 2021 letter to President Joe Biden comparing parent-led protests to domestic terrorism. The association later apologized.)

Thomas Jefferson High School parents have good reason to be frustrated right now. Because of the school’s fixation on leveling achievement, school officials decided not to distribute National Merit commendations that would have made some students eligible for scholarships. Asra, a journalist who formerly reported for The Wall Street Journal, obtained employee emails in a Freedom of Information Act request. Her research uncovered the school’s motivation for holding back the commendations: Apparently, employees didn’t want to hurt the feelings of students who didn’t receive a certificate.

Before Fairfax pushed the new admissions changes, Asra considered herself “a good PTSA mom.” But when she objected to the school board’s agenda, she was treated like an enemy.

When one mom tried to track down her son’s certificate, a school counselor falsely told her there was no formal paperwork. Norma Margulies, a Fairfax parent who immigrated from Peru, said the school district “seems to value obfuscation and deception.”

The Mother Science

WHAT’S IRONIC is that school districts are usually desperate for parents to be involved in their kids’ education.

“The most accurate predictors of student achievement in school are not family income or social status, but the extent to which the family … becomes involved in the child’s education at school,” according to the National Parent Teacher Association. The more parents are engaged and involved in what’s going on at school, the better each classroom performs as a whole.

It’s not about parental pressure. It’s about students feeling like parents care. There’s no substitute for that feeling. It’s the single best engine for driving kids to want to learn.

Source: PLF

When parents are excluded from the decision-making process at schools—when they’re told they’re not experts in equity, or they’re privileged, or they’re on the wrong side of history—they organize together to make themselves heard.

Source: Prodraxis

Studies show that parents helping with homework isn’t even what makes the major difference—it’s parents attending school events, volunteering, and becoming part of the school community.

In Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville calls association “the mother science.” The progress of all other sciences depends on people freely working together toward shared goals, de Tocqueville argued. That’s civil society. Not all problems can (or should) be solved through top-down political processes. Some need to be solved by people on the ground leaning in, getting involved, and forging connections with other community members.

That’s what usually happens at schools like Thomas Jefferson: Engaged parents create a healthy community around the school—not through top-down dictates but through spontaneous order. That kind of parental involvement makes the school as a whole perform better.

But recent equity-driven policy changes are coming through top-down political processes—through expensive consultants, school board policymaking, and questionably parsed language that sorts students into “privileged” and “underprivileged” identity groups, then adjusts the rules to control group-level outcomes.

“They have a maniacal focus on equal outcomes for all students at all costs,” Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin told 7News after the National Merit scandal broke in Fairfax County. “And at the heart of the American dream is excelling, is advancing, is stretching and recognizing that we have students that have different capabilities.”

That’s what parents want for their children.

“Real equity is actually teaching Johnny how to read, write, how to do math,” one mother argued at a Minnesota school board meeting to discuss new equity and inclusion policies. “How to think, not what to think.”

New Activists

ASRA NOMANI didn’t find out about her son’s National Merit commendation until two years after it was awarded. Thomas Jefferson never bothered informing her or her son.

In media interviews, Asra called it a “sabotaging of children.”

Source: PLF

“We all want every student to thrive in society and in our schools,” she added. “But we do not do that by denying kids opportunities. I think that’s something that we should all agree upon.”

For better or worse, school boards have turned parents like Asra into activists. When parents are excluded from the decision-making process at schools—when they’re told they’re not experts in equity, or they’re privileged, or they’re on the wrong side of history—they organize together to make themselves heard.

“I am not an activist by nature,” Wai Wah Chin, a New York City mother of four, told guests in her keynote address at PLF’s 50th anniversary gala. Yet when New York education officials started complaining there were too many Asian students at the city’s specialized high schools, Wai Wah co-founded the Chinese American Citizens Alliance of Greater New York and organized a campaign against Mayor Bill de Blasio’s changes to specialized high school admissions. All four of Wai Wah’s children attended Stuyvesant, one of the city’s best public schools. To Wai Wah, and other parents like her, schools’ shift in focus from education to equity is worth organizing against.

“There’s so many parents who have never been engaged in politics before,” Wai Wah told PLF. Some, like her, are immigrants. (Wai Wah’s family immigrated from China when she was a young child.) For these parents, Wai Wah said, “it means a lot to them to be able to come to America to take a test and be judged on their own merit—not to be judged by their class affiliation, or their parents, or their ethnicity.”

With PLF’s help, Wai Wah’s organization is challenging the New York admissions changes in court. Wai Wah went from being “not an activist” to becoming a well-known champion for New York students. She’s now so well-connected with other parents that she helped Students for Fair Admissions connect with plaintiffs to challenge Harvard and UNC’s affirmative action policies—a challenge that was successful at the Supreme Court in June.

“When something happens, do you stand up?” Wai Wah asked. “Or do you just say, ‘Okay, well, it’s not my battle.’”

When schools are at stake, she said, “it’s everybody’s battle.”

What Drives Parents

IF SCHOOLS’ EQUITY-FIRST policymaking revolves around race-based statistics, well-paid consultants, and a belief that all outcomes can be made equal, parents are driven by the opposite—parental love, the mother of all mother sciences, which is inherently unequal.

“To give yourself over in love to a little child, the most economically useless creature in the world, is to forget yourself and your immediate purposes,” Anthony Esolen writes in Nostalgia. Esolen then decries “those who would use children to further their political purposes.”

When this magazine went to print, California’s legislature still had the time—and technically, the votes— to override Governor Gavin Newsom’s veto on the bill that would criminalize some parents’ behavior.

But legislators may not go through with the override. Voters are parents, too.

The Supreme Court held in 2000 that “the interest of parents in the care, custody, and control of their children … is perhaps the oldest of the fundamental liberty interests recognized by this Court.” In Students for Fair Admissions, the Court also ruled that race-based college admissions violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution.

In addition to petitioning the Court to hear the Thomas Jefferson High School case, PLF drafted model legislation that would require the governing bodies of public schools to publicly post all their training and curricular materials concerning diversity, equity, and inclusion, so that parents aren’t left in the dark.

Parents want to know that their kids will be judged for who they are, not what racial category they were born into. They want to know that their kids will be given space to succeed, to fail, to be themselves.

To be free. ♦

Watch Fortune in the Book, PLF’s short documentary about the battle over equity at Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology.

555 Capitol Mall, Suite 1290

Sacramento, CA 95814