Fall 2022

Seven Deadly Sins

To read more about the work that PLF is doing, visit pacificlegal.org.

Halloween is a special time for the Andersons. It’s my wife’s favorite holiday and seemingly takes on increasing significance each year, as we accumulate more and more decorations in hopes of better attracting all the East Sacramento ghosts and goblins seeking treats. That includes a gigantic spider that rests on the roof just above our front door (and one in the tree and two on our porchlights and two more in the garden—and these are just the spiders).

This time of year, historically devoted to remembering the dead and departed, can take you on a temporary journey to some of the darker corners of the human psyche, whether through the costumes we wear, the pranks we pull, or the poor pumpkins we butcher. And while haunted houses and trick-or-treating are all in good fun (and fake), in the real world you can still see genuinely ghoulish behavior that’s no laughing matter, especially by those who aim to rule us. That’s bound to happen in a system where humans govern humans. As public choice economic theory explains, we’re all fallible and respond to incentives, and we are susceptible to the temptation of power.

This issue of Sword&Scales highlights several situations where government behaved badly because nefarious impulses proved far too strong. In keeping with our eerie seasonal theme, we’ve even labeled each circumstance in accordance with its corresponding sin: greed, pride, lust, wrath, gluttony, envy, and sloth.

Now, we believe there can be virtuous government. In fact, we already have the recipe. It’s the government inspired by the Declaration of Independence and created by the U.S. Constitution. It’s a government of limited, separated, and enumerated powers, dedicated to maximizing individual liberty and human flourishing. When government focuses on this aim and avoids its vices, we’re all the better for it.

And the news is not all melancholy—far from it. For nearly five decades, where government takes the wrong turn, PLF is there to guide it back. That’s especially true when the stakes are the highest.

Indeed, we’ll be arguing our 17th and 18th cases at the U.S. Supreme Court this very term. So far, of the 16 we’ve litigated there, we’ve won 14—and we’re hopeful we’ll add to the win column. We’re proud (but not too proud—that’d be a sin!) of this record, which is one of PLF’s differentiating factors. Not only that, we’ve accelerated our appearances at the Supreme Court, with 10 cases in just the past six years.

Of course, that’s only the U.S. Supreme Court. We have scores of cases in other federal and state courts around the country (likely including what will be our next Supreme Court case). Plus, as a full-service public interest law firm, we work to great effect in the court of public opinion, in legislatures, and in academia.

So, when your doorbell rings and a precocious phantom appears with an orange plastic jack-o’-lantern half-full with candy, forcing you to decide whether to hoard or give away those Reese’s Mini Peanut Butter Cups (hoard!), take comfort that PLF is on the lookout for the specters of government sin. And when we win, it’s pretty sweet.

Steven D. Anderson

PRESIDENT & CEO

Sin #1: Greed

Michigan officials steal families’ homes to pad their budgets

Christina Martin

Senior Attorney

greed: an intense and selfish desire for something, especially wealth, power

The house on Diamond Lake was estimated to be worth between $3 million and $4 million.

It was nestled on the shore with other multimillion-dollar houses in the postcard-perfect Michigan setting. “Diamond is a very appropriate name for this beautiful lake,” one visitor to the area reports on TripAdvisor. “The water is crystal clear and sparkles when the sunlight dances on its surface. Water sports and fishing are a constant presence. You will see sailboats whenever the wind picks up a bit.”

It’s no wonder Cass County officials were so excited.

“This is a major asset,” the county treasurer boasted in a 2014 meeting with the Board of Commissioners. “This probably won’t happen again while I’m treasurer.”

Cass County didn’t purchase the house on Diamond Lake. It seized it.

The homeowner had accumulated a property tax debt of about $100,000, including interest and fees. That allowed the county to foreclose on the multimillion-dollar home.

“It’s a done deal,” the county treasurer said. “They’ve tried to send us a check for $100,000, and I’ve returned it.”

She encouraged the commissioners “to collectively do some brainstorming” about ways the county could use the lakefront property. They could hold a public auction to sell the property for a profit, or they could keep the home for a while to host conferences and other events.

Either way, it was a windfall for the government. Private emails between county employees noted the treasurer was “tickled pink” by the acquisition.

“Have you ordered a new living room set for it yet?” one employee joked. “When is the first cookout?”

Profiting from tax foreclosures

It is inevitable—and, frankly, reasonable—that the government must sometimes foreclose on homes to settle outstanding tax debts. At some point, if a person refuses to pay their due, the community needs recourse.

But in states that still practice home equity theft—foreclosures in which the government pockets more than it is owed, simply because it can—the government is incentivized to pursue foreclosures.

That’s why Cass County’s treasurer rejected the $100,000 check from the Diamond Lake homeowner in 2014; the county preferred to have the multimillion-dollar house.

It’s also why so many homeowners report being completely blindsided by foreclosure proceedings: The state has no incentive to make sure they’re informed about what’s at stake.

In these situations, the government isn’t acting as a fair-minded collector anymore. It’s behaving more like a predator. It deepens people’s debt with high interest rates of 12%-18%, then moves in to seize and sell their homes at a high profit margin.

For some government officials, it’s no longer about settling debts.

It’s about how much they can get.

Tawanda’s story

Tawanda Hall, a nursing assistant in Michigan, was shocked when she found out the government was foreclosing on her Southfield, Michigan, home in 2016.

“They put the notice on the side of the house, on the garage, and not on the front where everybody was going in,” she says.

Her family’s tax debt at that point was about $22,000. Her house, which she lived in with her husband and children, was valued by the county at more than $205,000.

For the Halls, of course, the house also had sentimental value. It was the house they’d fixed up together as a family. Tawanda’s husband, Prentiss, put up the fence in the backyard and had a beautiful brick pathway put in. Their daughter celebrated homecoming there.

“It had a real big family room,” Tawanda remembers, “so we were able to hold a lot of people in one spot, and be able to enjoy each other… Lord, there were a lot of memories there.”

Tawanda’s father-in-law offered to help the family pay off their tax debt so they could keep the house. “I went down to the city council building,” Tawanda recounted in a video interview with John Stossel . “They said no. They didn’t want our money.”

“They wanted your house,” Stossel guessed.

The county got Tawanda’s house.

And this is where things get interesting.

The Southfield scheme

Oakland County prepared to put Tawanda’s house up for auction. But because of Michigan state law, cities have “first right of refusal” at county tax foreclosure auctions. A city needs only to pay the tax debt owed on a house to acquire it.

The City of Southfield “bought” Tawanda’s house from Oakland County for the price of her tax debt—the same debt that Tawanda was told it was too late to pay off.

Then Southfield promptly transferred ownership of the house—for the price of $1—to a private company called the Southfield Neighborhood Revitalization Initiative, LLC.

But the Revitalization Initiative is not just any company. Southfield’s mayor is a manager of the company and a board member of the nonprofit that owns it. So is the city administrator. And this company has made millions from tax-foreclosed homes. The Detroit News reports that the Southfield Neighborhood Revitalization Initiative made as much as $10 million between 2016 and 2019 flipping homes they acquired in tax foreclosures. Officials have claimed the money has been used to serve the public good, and that they have not personally profited from it. But the Revitalization Initiative and its parent non-profit—led by city officials—clearly reaped the benefits of these transactions.

After several Southfield homeowners sued the company, the Michigan Court of Appeals ruled in 2019 that the city’s cozy relationship with the Revitalization Initiative is not against the law—but that doesn’t mean the court liked it.

“The fact that elected officials were using their political status for private financial gain by obtaining properties before they could go to auction following tax foreclosures is, at a minimum , troubling,” the court wrote, before calling the behavior of Southfield officials “shocking to the conscience.”

It’s shocking, but it’s also shockingly profitable: The Revitalization Initiative sold Tawanda’s house for $308,000.

Tawanda’s family didn’t get a dime from the sale, of course. “You wonder, how do people get away with that?” Tawanda asks.

Another shady Michigan county

Oakland County’s neighbor, Wayne County, has its own questionable history with tax foreclosures.

A 2017 investigation by Detroit radio station WDET and Bridge Magazine revealed that Wayne County had grown financially dependent on the stream of easy cash from selling foreclosed homes at auction. It needed that cash to erase its deficits and balance the budget. Between the 2008 financial crisis and 2017, Wayne County raked in $421 million from the sale of foreclosed homes and the high interest rate it applied to back taxes. The county even began including projections for how much money it could make off foreclosure auctions in its financial “turnaround plan”—even though, as one former county executive told Bridge Magazine, “foreclosing on people’s homes shouldn’t be a policy to sustain yourself.”

And then there’s the treasurer’s wife.

Wayne County has a policy forbidding treasury employees and their family members from bidding on properties in county auctions. It’s a reasonable policy: County officials shouldn’t personally benefit from orchestrating the seizure and sale of other people’s homes.

So people were surprised when the Detroit Free Press revealed in 2020 that the county treasurer’s wife had bought several homes from the tax foreclosure auctions her husband oversees.

“A Wayne County resident with property in tax foreclosure shouldn’t have to wonder if the county treasurer chose to seize his or her home because the treasurer’s relatives wanted to buy it,” the Detroit Free Press editorial board pointed out.

Was the treasurer apologetic when confronted with evidence of his wife’s purchases?

Embarrassed? Nervous

Not at all: He told a reporter that the policy against employees’ family members participating in the auction was “intrusive and unrealistic” and he planned to change the policy.

The courts crack down

Michigan officials got a rude awakening in 2020, when the Michigan State Supreme Court sided with Pacific Legal Foundation client Uri Rafaeli in a particularly egregious case of home equity theft.

Oakland County had seized Uri’s modest rental house because Uri, an elderly man, accidentally underpaid his tax bill by $8.41. The county sold the unit at auction for $24,500 and pocketed everything.

PLF argued that what happened to Uri violated the Michigan State Constitution, which (like the U.S. Constitution) prevents the taking of private property for public use without just compensation.

Incredibly, Oakland County’s attorney defended the county’s racket by arguing that Michigan had become financially dependent on stealing from people like Uri.

“A ruling for the plaintiffs will ruin local governments,” the county’s attorney told the justices in oral argument. “That will come right out of schools, roads, firefighters, and other basic services.” Never mind that its gains were ill-gotten. The government’s argument seemed to be that home equity theft was keeping its coffers full.

Uri’s story appalled the court, which ruled that Michigan counties couldn’t keep surplus proceeds from tax foreclosure sales anymore. They could keep only enough to settle delinquent tax bills. Anything else needed to be refunded to homeowners.

The court ruling should have been the end of the fight.

But greed is a powerful motivator.

The cost of government greed

Tawanda Hall is still trying to hold the government accountable for stealing as much as $285,000 from her family. She and seven other Southfield homeowners are working with PLF in a lawsuit against Oakland County. If we’re successful, the lawsuit will prevent what happened to Tawanda from happening to anyone else.

Tawanda Hall wearing a shirt made in memory of her late husband, Prentiss.

This is a battle that Tawanda is forced to fight without the help of her husband, Prentiss. About six months after the county took the Halls’ home, Prentiss was found unconscious at his construction job. By the time he was discovered, his brain had been starved of oxygen for so long that he was left with severe brain damage.

“He wasn’t able to move, or eat, or anything,” Tawanda says. He died in hospice care shortly afterward.

Tawanda believes the stress from losing their home contributed to her husband’s death.

“How do you even sleep at night knowing that you’ve done this to several people and destroyed several families?” Tawanda wonders. “I just don’t understand.”

The government officials who maneuver predatory tax foreclosures aren’t thinking about the suffering of the families they leave behind.

They’re thinking about the spoils.

“Greed is a fat demon with a small mouth,” writes crime novelist Janwillem van de Wetering, “and whatever you feed it is never enough.” ♦

Sin #2: Pride

The EPA sees itself as a ‘clean water’ savior. But its mistakes are destroying lives.

Joseph Kast

Creative Manager

Paige Gilliard

Attorney

pride: an intense and selfish desire for something, especially wealth, power

We all have a slightly distorted idea about who we are and how other people see us. We tell stories about ourselves, rewriting history in our heads to fit narrative myths in which we’re the main character—the hero.

This is the origin story the Environmental Protection Agency tells about itself: On June 22, 1969, Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River burst into flames. TIME magazine put a stunning photo of the burning river on its front cover emblazoned with the headline, “An Ecological Crisis.” America had a serious pollution problem, and the public was clamoring for a solution—a savior. A year later in 1970, President Richard Nixon signed the EPA into being. Then in 1972, the EPA’s story goes, Congress gifted the young agency with sweeping powers to eradicate water pollution in America. And everything’s been better since.

Like all personal myths, of course, that story is only partially true.

Technically, it was an oil slick on the Cuyahoga River that caught fire—and it was put out 30 minutes later, before reporters or photographers could document it. The river had caught fire dozens of times in previous years. Few people even noticed the 1969 fire while it burned. But the right people knew how to make hay with the biblical image of water bursting into flames, and it became a TIME cover story. But TIME used an image from a previous 1952 Cuyahoga fire for its cover. The state of the current river was not quite the urgent, Old Testament crisis the magazine wanted to depict.

In truth, the creation of the EPA was the culmination of nearly a decade of growing environmental awareness and activism on top of a decades-long expansion of the role of the federal government in nearly every aspect of American society.

Throughout the 1960s, the ongoing Cold War and the very real risk of nuclear devastation weighed heavily on the entire country. Rachel Carson’s alarming 1962 book, Silent Spring, drew the public’s attention to the widespread use of harmful pesticides. Ralph Nader’s public interest activism marked a shift in liberalism away from New Deal-era trust in government toward a more cynical, watchdog attitude. The famous “Earthrise” photograph taken from the Apollo 8 in 1968 became an immediate symbol of the frailty of life on Earth.

Richard Nixon’s creation of the EPA was partly the end result of this environmentalist shift. In his State of the Union address that year, Nixon said, “Clean air, clean water, open spaces—these should once again be the birthright of every American.” It was a grand promise—and it would spark a grandiose 50-year mission.

Eliminating all ‘pollutants’

The Clean Water Act of 1972 was “implausibly ambitious” from the get-go, according to scholars David Keiser and Joseph Shapiro.

The CWA regulates the discharges of “pollutants” from “point sources” to “navigable waters,” which it defines as “the waters of the United States, including the territorial seas.” The word “pollutants” is broadly defined to include soil, sand, and rocks alongside the industrial and chemical waste that most people imagine. Anyone responsible for discharging these “pollutants” into “navigable waters” must get a permit from either the EPA or the Army Corps of Engineers, depending on the type of discharge involved.

Nixon initially vetoed the CWA. He was a “pro-environment” president—he created the EPA, after all—but he believed the Clean Water Act’s costs would be “unconscionable” and “budget-wrecking.” In his veto message, he said he hoped to solve the country’s pollution problem in “a way that does not ignore other very real threats to the quality of life[.]”

But Congress overrode his veto, and the CWA became law.

Murky waters

In the 50 years since the CWA was passed, the EPA has used it to assume authority over ever-greater areas of the United States.

While the CWA defines territorial seas, it does not define “the waters of the United States.” That phrase predates the CWA: It was used in the 1899 Rivers and Harbors Act, which prohibits obstructions “to the navigable capacity of any of the waters of the United States” and requires permits from the Army Corps of Engineers to build structures like piers, wharfs, and transmission lines in those waters.

Over the years, the EPA—convinced of the righteousness of its mission and the infallibility of its own expertise—has interpreted the phrase “waters of the United States” to extend its regulatory domain over not just waterways, but also inland wetlands.

The EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers have also interpreted their authority so broadly that they claim the right to regulate activities that might merely move dirt (in government-speak, “filled material”) into or on waters or wetlands. Moving dirt is, of course, a far cry from discharging pollutants into water. And yet, in an interview with PLF, legal scholar Jonathan Adler confirms the government’s position:

Government officials were saying that if there was a baseball game on a jurisdictional wetland and the guy walks with his cleats and bangs the dirt off of his cleats, that would be “redeposited filled material.” There’s a Federal Register notice in which EPA says the same thing about dirt being picked up and redeposited by the tread of a bicycle biking across the wetland. The claim that this is just about “regulating development” and “regulating commercial activity” is not true. The Act doesn’t limit anything that way, the “Waters of the United States” definition does not limit anything that way. And the agencies, in their own understanding of their own authority, have never limited it in that way.

If these sound like alarmist hypotheticals, consider that the government sued our client Jack LaPant simply for merely plowing his own farm. Or consider the case of Gaston Roberge, who owned a commercial lot and allowed the town to dump clean fill there. When he decided to sell the lot to a developer, the Army Corps of Engineers charged him with illegally filling a wetland. The developer, of course, immediately backed out. Environmental policy scholar R.J. Smith explains what happened next:

After six years and tens of thousands of dollars in legal fees fighting to get a permit, it turned out he didn’t need the permit after all, as his lot was finally designated as not a wetland. He then sued for a temporary taking of his property. During the proceedings, a Corps memo was discovered, saying, “Roberge would be a good one to squash and set an example.”

Priest Lake, Idaho, where Mike and Chantell Sackett’s property (marked by dotted boundary) has sat empty for over 15 years, surrounded by houses.

This is the attitude with which the Army Corps of Engineers and the EPA enforced the Clean Water Act. They wanted to make examples of people and demonstrate their own power. Roberge’s story is just one of many. Pacific Legal Foundation has defended countless people who found themselves mired in a “navigable waters” quandary.

For example: Richard Schok owns a successful pipe-fabricating business in Alaska. He purchased a property to expand his company, only to learn that, under the CWA, the new property was a “wetland.” But of the 350 acres on Schok’s property that the government called a “wetland,” about 200 of the acres were permafrost. Land that is frozen all year was now being deemed a “navigable water.”

PLF’s late client Joe Robertson was another CWA victim. A Navy veteran then in his mid-70s, Robertson was sentenced to 18 months in prison for allegedly violating the CWA. Robertson’s land in rural Montana was prone to forest fires. He ran a firefighting support-truck business. He dug small ponds in and around a one-foot-wide, one-foot-deep channel near his home to provide more water for fighting forest fires. The channel is 40 miles from any river on which a boat could float, but the government claimed Robertson was discharging a pollutant—soil—into navigable waters. He was hit with a $130,000 fine. Tragically, he didn’t live to see his vindication. PLF won the case and had the government refund his widow the thousands Joe had already paid in fines.

Another PLF client, Andy Johnson, was accused of violating the CWA for building a stock pond on his own property after securing the needed state permit. The pond provided reliable access to water for his small herd. Johnson had received permission from the local State Engineers Department to build the stock pond, and he’d done it in an environmentally friendly way. The water in it was crystal-clear. But the EPA demanded that Johnson remove the pond anyway, and threatened him with fines of $37,500 per day. All this, even though stock ponds are expressly exempt from the CWA. The EPA only dropped their threats a couple years later, when PLF helped Johnson file a lawsuit. Johnson agreed to plant willows around the pond but didn’t have to pay the agency a dime.

Ordering homeowners to comply

But what the EPA did to Mike and Chantell Sackett is especially outrageous: The agency has trapped the couple in legal purgatory since 2007.

It all started with the Sacketts’ purchase of a vacant lot in a subdivision near Priest Lake, Idaho. The Sacketts obtained local permits to build a home on their lot.

After construction began, the EPA ordered it halted. The agency then sent a compliance order declaring that the Sacketts’ lot contained wetlands that, because of their proximity to the lake, qualified as navigable waters—giving the EPA control over the Sacketts’ property. The couple were told they needed a federal permit to fill in the “wetlands” on their property (but in a voicemail to Chantell Sackett, EPA personnel said they’d never grant a permit to build there—putting the couple in a no-win situation).

To anyone who lacks the EPA’s regulatory imagination, of course, the lot doesn’t remotely resemble wetlands; it looks like what it is—a residential lot suitable for building a family home. The EPA itself acknowledges that no water at all, whether surface or subsurface, flows from the Sacketts’ lot to Priest Lake.

Not only did the EPA halt construction of the Sacketts’ home, but it also demanded expensive restoration work and a three-year monitoring program, during which the property could not be touched. The agency threatened the Sacketts with tens of thousands of dollars in fines if they didn’t obey the order. The Sacketts also were told they didn’t have a right to take the EPA to court: For decades, the EPA argued that no one could challenge their compliance orders in court—a stroke of particular arrogance. Unfortunately, lower federal courts usually backed up the EPA.

PLF disagreed with this dystopian stretch of government authority. We took the Sacketts’ case to the Supreme Court to establish that the couple had a right to appeal the compliance order. Justice Scalia delivered the unanimous opinion of the Court in March 2012. After seven years of legal battles, the Sacketts finally won the right to sue the EPA.

This October, PLF is bringing the Sacketts’ case back to the Supreme Court to resolve the bigger question: Does the Sacketts’ property really count as navigable waters, which would give the EPA power over this soggy residential lot? If so, how many thousands of acres across America will the EPA claim control over next?

The Sacketts’ arduous year fight with the EPA shows what happens when a federal agency aggrandizes itself.

To paint a clear picture of the EPA’s flimsy justification for its attitude toward the Sacketts: Along the north end of the Sacketts’ lot is a paved road; on the other side of the road, there is a man-made ditch, on the other side of which are wetlands. Running along the south end of the Sacketts’ lot is another road, across which sits a row of houses that front Priest Lake. There is no surface water connection between the ditch and the sacketts’ lot, or between the Sacketts’ lot and the lake. But because the ditch (on the other side of a paved road!) runs into a creek a few thousand feet west of the lot, and the creek flows into Priest Lake, the EPA claims that the Sacketts’ lot has a significant connection to the lake.

As Larry Salzman, PLF’s head of litigation, puts it, “What are we protecting at that point? There’s actually no world in which the EPA is protecting that lake from the Sacketts’ lot. They’re just asserting control over the surrounding property because they would like less of it to be developed around the lake.”

The EPA has assumed broad powers over America’s waters and skies. The agency says its mission is “to protect human health and the environment,” in part by ensuring that “Americans have clean air, land, and water.”

But harassing homeowners like the Sacketts does not make America’s water cleaner—and it’s a far cry from what Congress intended when it passed the Clean Water Act 50 years ago.

The EPA will be proudly celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act this October, right around the same time we’ll be arguing the Sacketts’ case at the Supreme Court.

This confluence of events should force the agency to ask itself some hard questions about costs and benefits—and about whether 50 years of exerting control over American lives and property has been long enough. ♦

Sin #3: Lust

This Montana city treats massage therapists like sex workers

Brittany Hunter

Editorial Writer

Daniel Woislaw

Attorney

lust: an unrestrained craving

Occasionally, Theresa Vondra gets a client who has the wrong idea about her massage business.

“We have had a couple instances where there’s been a gentleman who’s come in… and apparently, he was thinking he was going to be getting something else,” Theresa, a Montana masseuse and small business owner, says.

One client exposed himself to a massage therapist on Theresa’s staff. The therapist made him leave, and Theresa told the client never to come back to her business.

When things like that happen, it’s an objectifying, violating experience for a legitimate massage therapist like Theresa. Still, she says, “in all my years of doing massage, I think I could count on one hand the instances we’ve had like that.”

But now Theresa’s own government is treating her in a similarly objectifying, violating way—and unlike with a bad client, Theresa can’t bar the government from her business. In Billings, Montana, the local government is satisfying its lust for power by stereotyping and sexualizing all massage therapists, treating them like sex workers to gain access to their private property.

Theresa’s calling

Theresa wasn’t content to spend the entirety of her life working for someone else.

Breaking free from the monotony of the typical 9-to-5, she took the entrepreneurial route, opening a massage therapy business in her hometown of Billings.

Massage therapy hadn’t always been her dream. Like many young adults, Theresa for a time had been unsure of where she wanted to go with her career.

While she figured it out, she took a job in a chiropractor’s office. It was there that she fell in love with helping people achieve total body wellness.

Armed with her newly realized calling, she headed off to massage therapy school.

The decision to start her own business came with a fair share of obstacles. She was new to the world of entrepreneurship and had to learn on the spot the ins and outs of running a company.

All her hard work paid off. Just seven years later, her business is thriving and she now employs five massage therapists.

Theresa takes great pride in her profession. Every day she gets to ease the pain her clients experience not only from physical injuries, but from psychological trauma as well.

It’s rewarding work, but not everyone views the massage therapy industry in such a positive light.

Massage therapy is a tricky business, thanks to the country’s sordid history of “massage parlors” pretending to offer therapy, when in reality they offer… shall we say, unsavory and illegal services.

Even though Theresa runs an honest business, the stigma tied to the industry still impacts her work.

Billings’ new law

Compared to the hustle and bustle of big cities like New York and Chicago, Billings is a quiet, western town tucked away in the mountains.

Quiet though it may be, the area still has its fair share of illicit businesses—some of which hide behind the legitimacy of massage therapy.

Around the time Theresa began practicing massage therapy, the neighboring state of North Dakota experienced an “oil boom.” Consequently, Billings saw an influx of transplants, primarily from Texas, who had followed the money to the mountain states.

Shady businesses—including possible sex trafficking operations—also followed the money.

Concerned about potential sex trafficking on their own turf, city officials decided it was time to crack down—not just on credible threats, but on every single massage therapist in the city.

Under newly adopted legislation, Billings now requires licensed massage therapists to allow law enforcement into their establishments anytime, unannounced, to conduct warrantless searches of their business.

No complaint needs to be made, nor any suspicion raised, prior to the search—it is left entirely to the government’s discretion.

The Fourth Amendment was included in the Bill of Rights specifically to prevent the government from arbitrarily invading an individual’s privacy and property. Billings officials are not legally allowed to use the fear of sex trafficking to sidestep the Constitution.

That hasn’t stopped them from trying.

Anyone who refuses to agree to this new requirement is not only subject to a search; they also face fines, loss of license, and even jail time.

It should be noted: These searches aren’t just casual pop-ins where an officer comes in and looks around to see that everything is in order. No, the law allows armed law enforcement to enter the premises and look in “all rooms, cabinets, and storage areas.” It also forces business owners like Theresa to turn over very sensitive patient records—constitutional rights be damned.

Each of Theresa’s clients has unique circumstances and reasons for seeking massage therapy.

When her clients complete their intake forms, they are asked if they have any past trauma so that the therapists are sensitive and aware of any trigger that may come up during a session. This is very personal information that law enforcement now may access .

Not to mention, because the law lets them search everything on the property, that means they can go through client and employee belongings that are placed in lockers outside the massage rooms. Anything on the premises is fair game. And the law does not limit searches to possible evidence of sex trafficking or massage-therapy regulations but allows the police and code enforcement officers to look for violations of any civil or criminal law.

Theresa has an obligation to protect the privacy of her clients—not only for her personal ethical standards, but legally as well.

Billings’ outrageous law has left her feeling powerless to fulfill her duty to her clients. It also jeopardizes her livelihood. Imagine you’re a first-time client waiting for your appointment when, suddenly, cops barge in and begin searching the property.

Logically, you would think some red flag must have been raised to cause such a stir. You might feel uneasy about continuing with your appointment and decide to go somewhere else, justifiably so.

That is one possible scenario that worries Theresa. But she’s also worried that the law is so vague that it opens up her employees to potential legal nightmares.

It says, for example, that no lubricants can be used in massage businesses. But there is no definition as to what constitutes a lubricant. Massage oil could technically fit the bill, and it will be found in any legal massage therapist’s office.

The potential for this law to be abused by law enforcement is frightening.

As if this weren’t bad enough, Billings’ new law applies to home-based businesses as well.

For therapists who operate out of their homes, this means not only having the privacy of their business violated, but also every single aspect of their personal lives. Nothing is off limits as long as it is on the property where massages are given.

The realities of sex trafficking

Sex trafficking is, of course, a heinous crime. But the assumption that the massage therapy industry is a hotbed for sex trafficking is, in fact, overhyped and vastly flawed.

As Deborah Kimmet points out in her research study, “Human Trafficking Hijacking the Massage Therapy Profession,” the vast majority of massage therapy businesses are law-abiding with absolutely no ties to sex trafficking. As Kimmet writes, “Legitimate massage therapists are already dealing with the stigma of being associated with prostitution and other sexual crimes.” There is no valid reason for governments to add to existing stigma with unconstitutional laws.

Treating honest people like Theresa as potential sex traffickers without any proof is wrong. A staple of our U.S. legal system is the presumption of innocence.

Each person is innocent until proven guilty. If the government believes there is credible evidence of a crime, they must obtain a warrant before violating a person’s Fourth Amendment right to be “secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures.”

Local governments are not allowed to ignore the Constitution’s promise of individual privacy whenever they please—especially in the absence of probable cause. And the mere act of practicing massage therapy is not probable cause.

Painting Theresa and other legitimate businesses as potential perpetrators of heinous sex crimes is a slap in the face. Theresa’s employees already have to deal with the occasional lustful advance from a creepy client. Now they’re also dealing with a far-more-constant and persistent threat: a government intent on spying on and sexualizing their legitimate business.

There are better ways

Theresa was against this law from the moment it was proposed. As its passing began to seem likely, she decided to fight back, not just for the privacy of her own business but to protect her clients and employees from the long arm of the government.

In conversations with Theresa, city officials acknowledged that her business is above board. Even so, when she pushed back against their plans, she was told to “take one for the team.” As if objecting to the bill somehow made her a sex trafficking sympathizer.

Pacific Legal Foundation is helping Theresa and other Billings-based massage therapists stand up for their constitutional rights against the city’s attempt to violate their privacy.

There is no rational justification for the city to go to these extremes to stop sex trafficking. Warrants work. When Billings law enforcement suspects a non-massage business of criminal activity, they obtain a warrant.

The government’s lust for power and control cannot trample constitutional rights. That’s how authoritarianism creeps in.

This won’t stop with massage therapy businesses

The Billings law is not an aberration, but rather representative of a trend by which local, state, and federal governments require law-abiding citizens to surrender a constitutional right as a condition of using their own property or pursuing a livelihood or hobby.

Now, in the wake of COVID-19 and the new work-from-home reality for many Americans, governments aren’t just trying to get inside commercial businesses to “inspect” for “compliance” without obtaining warrants. Those business places are often private homes. In its lustful bid for power over the lives and fortunes of everyday working Americans, regulators are claiming the right to worm their way—without warrant or cause—into the homes and businesses of cake bakers, upholsterers, short-term landlords, ham radio operators, dog breeders, and more.

No one should have to choose between their livelihood and their property rights—which is why Pacific Legal Foundation represents people like Theresa. ♦

Sin #4: Wrath

California fines doctor millions for protecting people from 20-foot drop

Joshua Thompson

Director of Legal Operations

wrath: retributory punishment, divine chastisement

The 12 gods of ancient Greece were vengeful and petty.

Hermes once turned a nymph into a tortoise because she didn’t show up for Zeus’ wedding. Apollo skinned a flute player who challenged him to a contest. Demeter condemned a king to eat his own flesh because he cut down the wrong tree.

These punishments were not acts of justice. They were acts of wrath. The gods condemned anyone who made them angry—even people who didn’t do anything wrong.

The fine

It was simply a devastating amount of money: $4.185 million.

Warren and Henny Lent were shocked. The fine was far, far higher than the $600,000 settlement the commission had tried to negotiate before its kangaroo-court “hearing.” It was far higher than the commission’s own staff had recommended.

The purpose was to utterly crush the Lents. Cruelty was the point.

The 12 members of the California Coastal Commission decided on the amount, and they hadn’t needed any court’s approval. After all, the commission is “the single most powerful land use authority in the United States,” as UCLA Law Professor Jonathan Zasloff puts it. Now the commissioners were flexing their recently acquired power: the power to punish.

One commissioner, pushing for the higher fine, reasoned that the commission didn’t “want to be in a position [of] rewarding… applicants that have been fighting us and resisting these types of opportunities.”

What happened to Warren and Henny Lent is as baffling and tragic as a Greek myth. It shows the consequences of giving authorities the power to act vindictively, outside the bounds of reason.

Before you read on, we should warn you: This is not a fairy tale with a happy ending.

This is a horror story.

The Lents

Warren Lent is a plastic surgeon in Beverly Hills. He knows how that sounds. “Everyone immediately thinks, ‘Beverly Hills plastic surgeon, this guy must be loaded as all heck,’” he told Pacific Legal Foundation when we started working with him in 2019.

He and his wife, Henny, didn’t grow up rich. Warren’s dad was the plant manager at a factory in New York; his mother was a legal secretary. Henny’s parents are both Holocaust survivors. “Both of our parents worked extremely hard just to make ends meet,” Warren said. As kids, Warren and Henny both grew accustomed to not getting things they wanted, “and those kinds of people grow up with dreams,” Warren explained.

One dream he and Henny shared was to someday own a house on the beach. For years, Warren worked at two different practices, 25 miles apart, so he could save up enough for a down payment.

“It wasn’t like we’re some wealthy family and have tons of money and we can just purchase anything,” Warren said. But he was a successful doctor, and over time, the couple’s finances grew.

In 2002, the Lents bought a three-bedroom house in Malibu on the Pacific Coast Highway. The house, built in the early 1980s, had a gate on one side with an exterior staircase that led down to the house’s deck, then down farther to the beach below. The gate and staircase were a nice safety feature: Otherwise, there would be a steep, dangerous drop.

The house was in a beautiful spot. The beach, Los Flores Beach, is a narrow, quiet strip of sand. When it’s low tide, you can walk along the shore for miles.

It was what the Lents had saved for. But they never really had a chance to be happy there.

“Personally,” Warren said, “I have had extremely little peace and enjoyment from the property.”

A couple months after they purchased the house, one of their new neighbors mentioned a problem with the property: The house’s original owners had an easement agreement with the California Coastal Commission. The exterior stairway jutted two feet into the easement—a violation of the original agreement.

“I started digging into it, and then I found out what kind of a mess we were in,” Warren said.

The commission

To people who don’t live in California, it’s hard to describe the kind of power that the California Coastal Commission wields.

The commission was established in 1972 to “help local governments adopt local coastal plans,” Kimberley Strassel writes in The Wall Street Journal. “Instead, it pulled a Saddam, investing itself with dictatorial powers over every last grain of the state’s 1.5 million acres of coastal property—public and private.”

Its 12 commissioners control development of all coastal property in California, up to 1,000 yards (over half a mile) inland from the shoreline.

“The commission basically tells us what to do, and we’re expected to do it,” Jeff Jennings, then-mayor of Malibu, told The New York Times in 2008. “And in many cases that extends down to the smallest details imaginable, like what color you paint your houses, what kind of light bulbs you can use in certain places.”

“The California Coastal Commission is known as an activist—some might say aggressive—agency that interprets its statutory powers broadly,” the Los Angeles Times editorial board acknowledges.

During its early years, the commission would force coastal property owners to sign easement agreements in exchange for permit approvals. You couldn’t build your home unless you agreed to give the commission permanent rights to use part of your property.

But PLF client Patrick Nollan stood up to the commission in 1982. The commission had refused to grant Pat a permit unless he gave up about a third of his property for public use. “If the state can just take your property, I think that’s wrong,” Pat told the Los Angeles Times. “It’s a basic issue of fairness.” In 1987, Pacific Legal Foundation brought Pat’s case to the Supreme Court, which ruled against the commission, calling its scheme an “out-and-out plan of extortion.”

Unfortunately, the victory in Nollan came too late for the original owners of the Lents’ Malibu property: To get the commission to approve their permit to build in 1978, the original owners had to provide the commission with a public access easement.

And yet, when construction finished in 1983, the house included a gate and stairway which partially blocked the space the owners had promised to the commission.

In the original owners’ defense, building the gate was necessary: Without it, pedestrians might fall down the dangerous 20-foot drop from the sidewalk to the beach.

Plus, they might have reasoned that if the easement was important to the commission, surely it would make plans to build the accessway and alleviate the hazard. But after demanding the easement, the commission did absolutely nothing.

So decades went by, with the house—and its stairway—sitting peacefully on Los Flores Beach.

The dispute

“People love to make fun of doctors and how stupid they are in business situations,” Warren said, “and I guess I’m the poster child for that.”

The Lents didn’t have a lawyer review the property title when they bought the house in 2002. Until their neighbor mentioned it, they had no idea any easement issue existed.

Then, in 2007, five years after they bought the house, the Lents received a “Notice of Violation” letter. The commission was demanding the removal of the gate and stairway, calling them “unpermitted.” The Lents responded, requesting that they be allowed to keep the stairs and gate in place until the commission was ready to develop the public accessway.

Thus began a nine-year argument between the Lents and the California Coastal Commission.

“Every letter that my attorneys sent to them always said, ‘When you are ready to build this, we will remove all structures,’” Warren said.

But that did not satisfy the commission. Its demands were inelastic, irrational. They wanted the gate and stairway removed without a second thought. Even though removing the structures would create a dangerous drop-off, the commission was insistent.

It didn’t like being questioned.

The punishment

In 2014, the California State Legislature bestowed a startling new power on the already-powerful California Coastal Commission: It would now be able to impose fines of up to $11,250 per day to force compliance with their orders.

That’s when the Lents’ situation took a sinister turn.

“They started talking to us about a $600,000 penalty,” Warren said. “I was thinking, ‘I don’t have $600,000. Where am I going to get $600,000 from?’”

The Lents tried to work out a settlement agreement: Even though the gate and stairway were part of the house when they bought it, they would remove them and pay a $100,000 penalty.

But now that it had its new power to fine, the commission wasn’t satisfied.

It wanted to punish. It wanted to make an example out of anyone who dared question its dictates.

Everything came to a head at the Lents’ hearing before the commission on December 8, 2016. Commission staffers recommended a fine of $950,000. It was an astronomical amount of money—but it was not high enough for the commissioners.

They settled on $4.185 million instead.

“This would destroy a lifetime of work,” Warren wrote afterward in The Wall Street Journal.

Pacific Legal Foundation worked with Warren to challenge the fine as a violation of the Eighth Amendment’s protection against excessive fines. We tried to bring the case to the Supreme Court, but the Court denied our cert petition.

As shocking and incomprehensible as it is, the fine stands.

And what exactly was the Lents’ crime?

“I mean, when you sit down and the dust settles, you say, ‘What did Warren and Henny Lent do? They bought a house on the beach to fulfill a lifelong dream,’” Warren said. “That’s all we did.”

It has been over 40 years since the California Coastal Commission extorted an easement out of the original owners of the house on Los Flores Beach. And as far as anyone can tell, as of this writing—even after its battle with the Lents—the commission has yet to open a public accessway on the easement.

It fined the Lents $4.185 million. It destroyed a lifetime of work. For an easement that the commission still has no interest in opening or ever using. It was purely for show.

For the commission, this wasn’t about the easement. It was about crushing someone who questioned the commission’s dictatorial commands.

“I would say that before this whole incident came up, I was a big believer, a big patriot,” Warren told us. “I believed in the United States.”

His experience with the California Coastal Commission shook him.

“It’s a small group of people who have the power to do this,” he said, “and they can squash any citizen like a little bug.” ♦

Sin #5: Gluttony

Louisiana legislators demand meatpacking monopoly

Anastasia Boden

Senior Attorney

gluttony: characterized by a limitless appetite

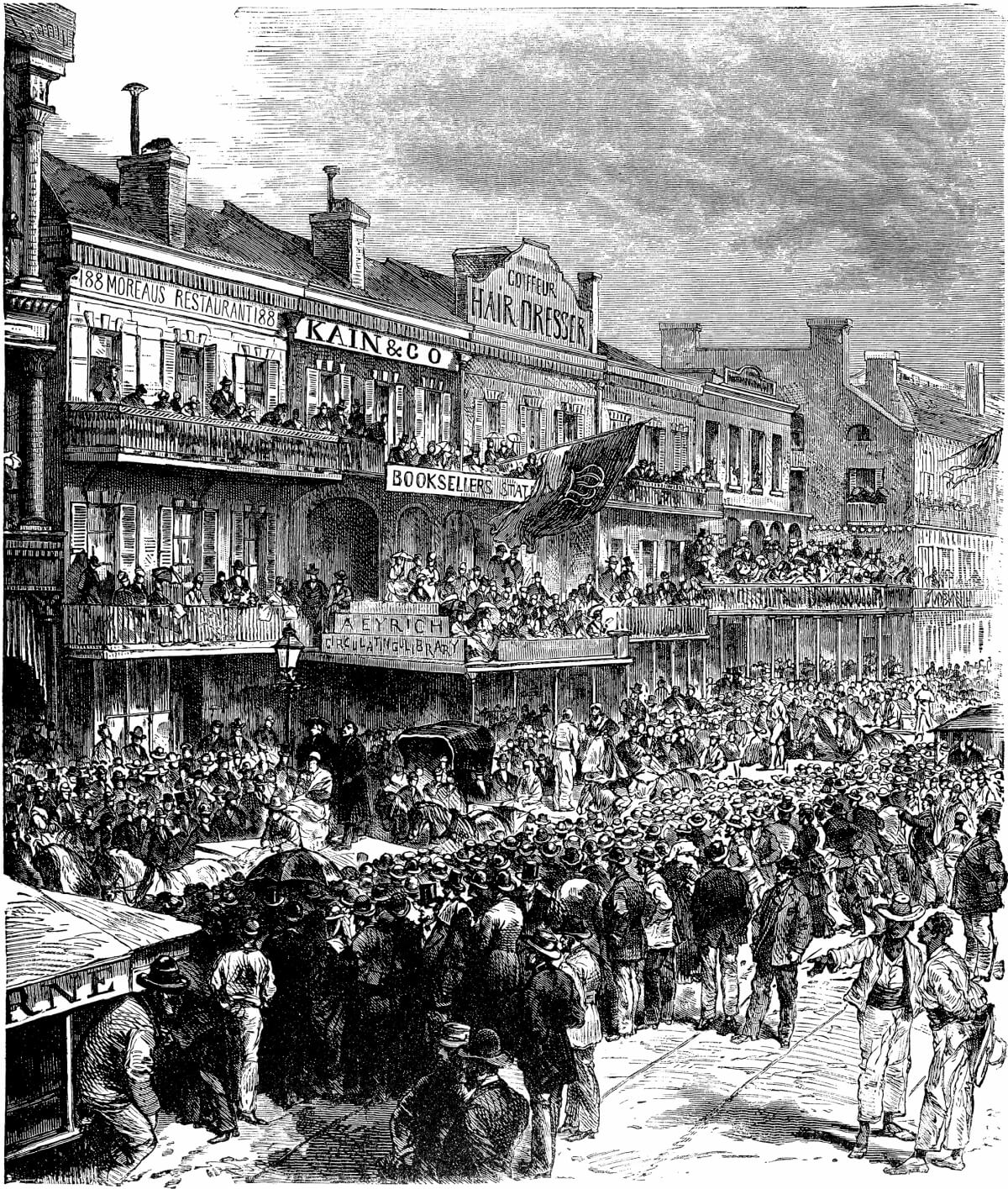

It was the late 1860s, and the city of New Orleans had a gruesome problem: Animal intestines clogged the city’s water pipes.

The drinking water was tainted: It contained bits of meat and offal from slaughterhouses a mile and a half upstream, where butchers gutted 300,000 livestock every year. Because of its proximity to Texas, New Orleans sold huge quantities of beef—and now the byproducts haunted the city. One doctor called New Orleans “a great Golgotha,” referring to the biblical site of Jesus’ crucifixion (from Matthew 27:33-35: “They were come unto a place called Golgatha, that is to say, a place of a skull…”).

The Civil War had ended and the Gilded Age had not quite begun. There was a restlessness in the air. New people flooded into New Orleans, mostly men looking to build fortunes in the wake of war. New technology was being developed across the country, but much of it still existed only on paper. Refrigeration hadn’t made it to the Bayou yet. The first American patent for an icemaker was issued in 1851; the first for a refrigerated train car came in 1867. The country was in the early stages of building a better, cleaner life.

But for now, the summers were inescapably hot—and there was blood in New Orleans’ water.

It was a serious public health concern. The health officer for the Third District reported that “[b]arrels filled with entrails, livers, blood, urine, dung, and other refuse in an advanced state of decomposition are being constantly thrown into the river[.]” The contaminated water spread cholera and yellow fever throughout the city, killing thousands.

Something needed to be done. The slaughterhouses upstream of the city’s water supply would have to be relocated.

But what the State of Louisiana chose to do instead—after being lobbied and bribed by a motley group of crony capitalists—was set up a state-enforced monopoly that swallowed the entire butcher industry whole.

A backroom deal

The 17 men who hatched the scheme weren’t even butchers.

One was the London-born owner of a New Orleans hat shop. Another was a cotton broker who later became implicated in an unrelated bribery scheme involving Audubon Park. Several of the men had already pushed their way into exclusive government contracts for a variety of odd jobs around the country related to canals, debris removal, and supplying city gas.

“The organizers appear to have been a devious lot,” authors Ronald M. Labbé and Jonathan Lurie note in their book, The Slaughterhouse Cases.

The hat salesman, William Durbridge, owned land south of New Orleans. It would make a perfect site for a new slaughterhouse, Durbridge and his compatriots decided—the only New Orleans slaughterhouse.

All they had to do was convince the state to incorporate their 17-man group as a company with exclusive rights to operate a slaughterhouse in New Orleans.

It wouldn’t be that hard. This was 19th-century Louisiana, after all. Political corruption was “a way of life, inherited, and made quasi-respectable and legal by the French freebooters, who founded, operated, and left us as the governmental blueprint that is still Louisiana’s constitutional and civil law,” former Louisiana Lieutenant Governor William J. Dodd writes in his book, Peapatch Politics.

Several of the 17 men were friendly with Louisiana’s youthful new governor, Henry Clay Warmoth, who had just taken office in 1868 at the age of 26. The men began to visit Governor Warmoth at his home to discuss the possibility of a new state law granting them a slaughterhouse monopoly.

By March 1869, the Louisiana State Legislature was considering a bill that would charter “Crescent City Company” and give it exclusive rights for 25 years to operate a “Grand Slaughterhouse” in New Orleans. Every butcher in the city would have to pay the company a fee to rent space at their slaughterhouse. If a butcher slaughtered livestock anywhere but Crescent City, he’d be fined. Crescent City would also retain the right to collect scraps from their tenant butchers to turn into feed they could sell for a profit. The state would appoint a beef inspector to inspect all meat on premises. (Unsurprisingly, the inspector eventually appointed was a good friend of Governor Warmoth.)

Some of the 17 Crescent City incorporators were actually in the room with legislators for the debate about the bill. William Durbridge later admitted that he and his compatriots paid for “fires, committee rooms, sandwiches, whiskey, [and] brandy” for the legislators. Another one of the schemers later said—under oath in an 1871 lawsuit involving Durbridge’s company shares—that “there was some considerable money advanced” to legislators. It was long rumored that some legislators held stock in the company through an arrangement that kept their names off the official stock book.

Not all of Louisiana’s legislators were on board with the scheme.

“No objection can be made to the removal of the slaughterhouses below the city,” one reasoned, “but it does not follow that there should be a monopoly of the slaughterhouse business.”

“Who are the men composing this company?” another legislator demanded. “Who are they? They are not butchers. They are not cattle dealers… We do object that these men should come along to rob our people, to steal away their property, to disturb our firesides.”

Despite these objections, the bill passed. Governor Warmoth signed it on March 8, 1869.

After it was signed, one of the bill’s main opponents, former Union Army General William L. McMillen, was so disgusted with the entire affair that he suggested the bill not be read aloud in the statehouse, as was customary, “in order that gentlemen not be troubled with qualms of conscience.”

The gluttonous nature of government

The legislators’ willingness to go along with the Crescent City proposition reveals two things about Louisiana state government in 1869.

First, of course, is the ordinary, self-serving avarice of the legislators who accepted bribes. The judge in William Durbridge’s eventual lawsuit against other Crescent City incorporators even noted in his ruling that “members of the House of Representatives were bribed for their votes and members of the Senate were also bribed for their votes… and I think the evidence is irresistible that the Governor’s signature to that bill was obtained by the same soft solder.”

But there’s also something more sinister at play in the government’s action.

By imposing a monopoly instead of simply relocating the offending slaughterhouses, the state revealed its reckless appetite for subsuming spheres of private activity under centralized control, an act that is inevitably infected with cronyism.

Rather than narrowly tailor a solution to the problem of New Orleans’ tainted water, the state readily accepted the Crescent City schemers’ argument that the government could reorganize the entire New Orleans butcher industry under the central command of a few favored state cronies.

With its slaughterhouse bill, the state absorbed the decision-making power of thousands of individual butchers, expanding the reach of government—and eating away at the freedom of New Orleans butchers.

The butchers push back

New Orleans did not react well to the Crescent City company’s new state-enforced monopoly.

The Daily Picayune complained that the state had put “the whole community” of New Orleans “under embargo to a few rich men.”

The New Orleans Republican asked why the monopoly was necessary for public health, which surely “will not suffer from three or four small slaughterhouses at proper points.”

New Orleans butchers were furious. Many of them were French-born immigrants who didn’t speak English; they didn’t have the political connections that the Crescent City incorporators did. Suddenly, the state was forcing them all to rent workspace from Crescent City’s “Grand Slaughterhouse” or abandon their livelihoods.

At a meeting of the Butchers Benevolent Association, organizers declared that every man had the right “to accumulate property by his labor… without the control, domination, or direction of any other person or persons in the community for their own emolument.”

The butchers’ first lawsuit against the Crescent City company was filed in May.

“The butchers are not only fighting their own battle,” The New Orleans Bee mused, “they are fighting the battle of the community.”

A 19th-century illustration of a street in New Orleans on Election Day.

‘Greedy appetites’

Six separate lawsuits over the New Orleans slaughterhouse monopoly were eventually consolidated at the Supreme Court in 1872 as the Slaughterhouse Cases.

John Campbell, attorney for the butchers, argued that Louisiana’s slaughterhouse bill violated America’s new Fourteenth Amendment, adopted in 1868, which says (among other things) that “[n]o state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.”

There’s vast evidence that the Clause was intended to prohibit states from violating the Bill of Rights or infringing other natural rights, and to enshrine in the Constitution those rights guaranteed by the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Chief among those rights contemplated by the Civil Rights Act were economic rights, which would ensure freed blacks would be able to thrive in the aftermath of the Civil War.

“[A]s man has a right to labor for himself, and not at the will, or under the constraint of another, he should have the profits of his own industry,” Campbell argued.

Campbell was a brilliant orator and a deeply flawed man. He was a former child prodigy, a former slaveholder, and a former Supreme Court Justice: He’d served on the Court from 1853 to 1861 before leaving to become assistant secretary of war for the Confederacy. Now Campbell was using the Fourteenth Amendment—adopted after the Civil War to protect the rights of freed slaves—to argue the butchers’ case before his former colleagues on the Court.

He described the Crescent City company as a “corporation [that] stalked and strutted through the land as a seigneurial power.” The Fourteenth Amendment, he said, “guaranteed its protection against sordid interests, selfish aims and ambitious usurpations, or greedy appetites.”

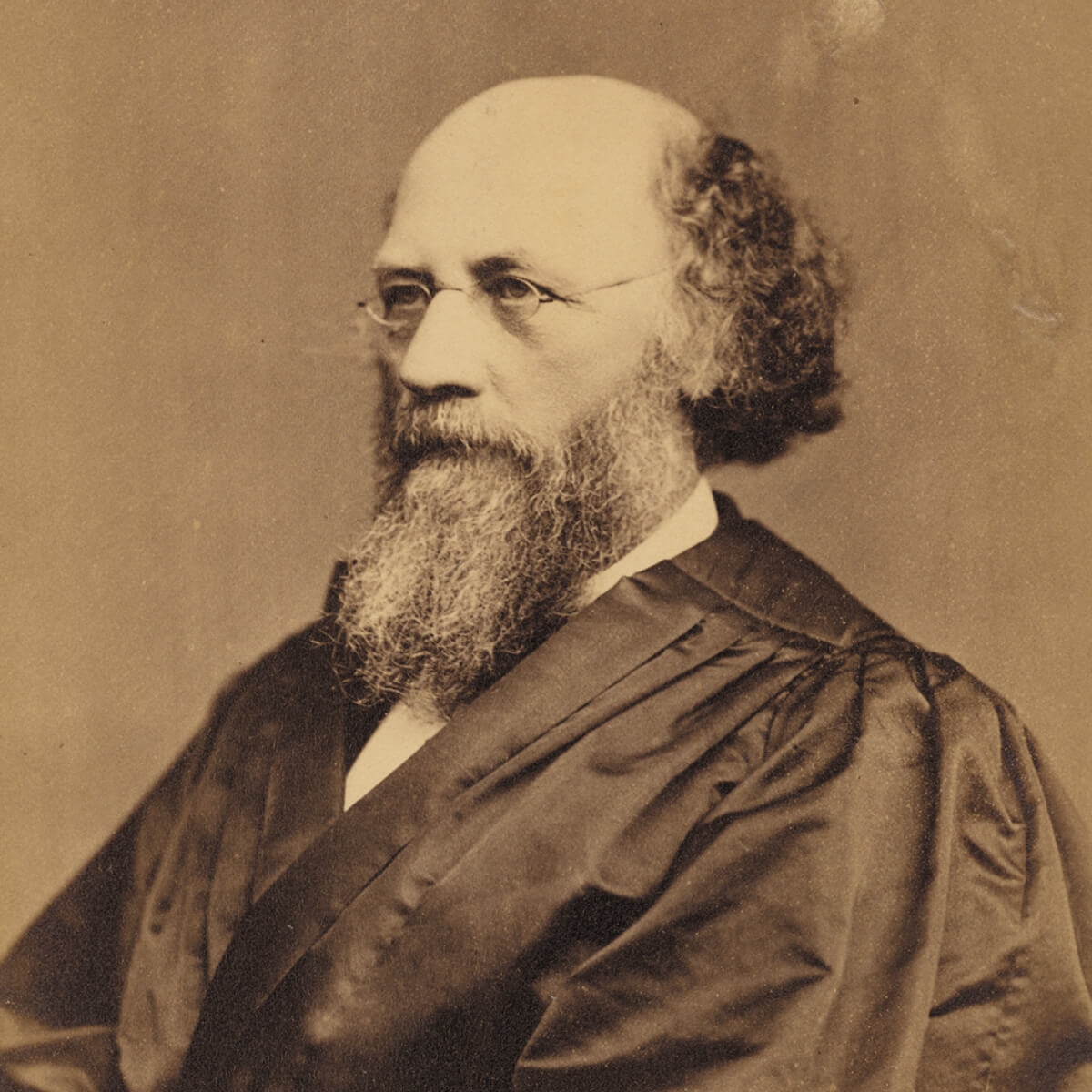

But in a 5-4 decision announced on April 14, 1873, the Court sided with the Crescent City crony capitalists and the State of Louisiana.

Justice Samuel Miller, the former Kentucky doctor who wrote the majority opinion, argued that the Fourteenth Amendment’s “privileges or immunities” clause only protected certain federal rights, like habeas corpus, access to navigable waters, and movement between states.

It didn’t protect “the citizen of a state against the legislative power of his own state,” according to Miller. States were free to violate the Bill of Rights and unenumerated rights, like economic liberty.

The decision effectively nullified the “privileges or immunities” clause, imbuing it with so little power that not only did it fail to protect the New Orleans butchers—it would also fail to protect black Americans from racist state laws for the many fraught decades to come.

Justice Miller’s opinion “turns, as it were, what was meant for bread into stone,” Justice Noah Haynes Swayne’s dissent lamented.

In a separate dissent, Supreme Court Associate Justice Stephen Field wrote that the majority turned the Privileges or Immunities Clause into “a vain and idle enactment, which accomplished nothing, and most unnecessarily excited Congress and the people on its passage.”

The Slaughterhouse legacy

Despite Crescent City’s victory at the Court, the state-enforced monopoly didn’t last long.

In 1879 Louisiana adopted a new state constitution that expressly forbade the legislature from granting “special or exclusive” rights to any corporation. The constitution also abolished “the monopoly features” in existing Louisiana corporate charters—including Crescent City’s. Other companies could now apply to operate slaughterhouses in New Orleans.

Supreme Court Associate Justice Stephen Field, author of one of three separate Slaughterhouse dissents.

But Justice Miller’s Slaughterhouse decision had already left a permanent mark on the whole country.

The decision discouraged federal courts from interfering with state laws that violated individual rights—especially economic liberty.

It encouraged states to prop up monopolies and licensing regimes that asserted centralized control over industries—expanding the role of the government in private spaces.

“Gluttony is about not knowing when to stop,” Claremont McKenna College Professor John J. Pitney tells OZY media, “and that applies to lots of areas of political life.”

The Slaughterhouse Cases reveal a government unwilling to check itself, even as it consumed the economic liberty of people it was meant to represent. Pacific Legal Foundation now fights for entrepreneurs whose livelihoods are stifled by heavy-handed government. These entrepreneurs’ fight, like the butchers’ fight, is not theirs alone. Any battle to defend economic liberty should be a battle of the American community. ♦

Sin #6: Envy

Education officials spread poisonous myth that Asian students are ‘test-taking robots’

Erin Wilcox

Attorney

envy: a feeling of resentful longing aroused by someone else’s possessions, qualities, or luck

“I walked into Stuyvesant High School and I thought I was in Chinatown,” Milady Baez, then-deputy chancellor of the Department of Education in New York City, complained to colleagues at a 2018 meeting. Baez’ point was clear: There were, in her opinion, far too many Asian American students at the city’s top magnet school.

Baez was penalized (although not fired) for her remark. But she was only expressing what other government officials and educators have said in so many words: that Asian Americans are unfairly overrepresented at the nation’s top schools and universities.

One New York University professor described it as “opportunity hoarding” by “privileged racial and ethnic communities.” Former Virginia Secretary of Education Atif Qarni compared Asian American families’ test prep to “performance-enhancement drugs.” Then-New York City Chancellor of Schools Richard Carranza said, “I just don’t buy into the narrative that any one ethnic group owns admission to these schools.” Alison Collins, vice president of San Francisco’s Board of Education (until she was recalled this year), tweeted that Asian Americans “use white supremacist thinking to assimilate and get ahead.”

Sometimes anti-Asian resentment boils over into unfiltered hate: California Assemblywoman Cristina Garcia was so upset by the defeat of an affirmative action proposition that she said in a closed-door meeting with colleagues: “This makes me feel like I want to punch the next Asian person I see in the face.”

The Asian stereotype

Believe it or not, there is academic research that helps explain why people like this are angered by perceived Asian American success.

A study by researchers at Princeton, Northwestern, and Lawrence universities found that people tend to stereotype groups along two axes: warmth and competence. If they stereotype a group as warm but not competent, they feel pity. If they stereotype a group as neither warm nor competent, they feel disgust. If they stereotype a group as both warm and competent, they feel admiration. If they stereotype a group as competent but not warm, they feel envy.

Families protest admissions changes at Thomas Jefferson High School in Northern Virginia.

The researchers found that many people stereotype Asians as highly competent but cold—“test-taking robots with no personality,” as Kenny Xu, author of The Inconvenient Minority, puts it. People who stereotype Asians in this way can start seeing them as a competitive threat, and become envious.

And envy can be dangerous.

“In its most virulent form, envy is characterized by a desire to take away the coveted object or advantage from the other—even when depriving them means losing something ourselves,” Anne Hendershott writes in The Politics of Envy.

Some people are willing to lose a lot in order to deprive Asian Americans of seats they’ve earned at top schools.

They’re even willing to lose American meritocracy.

An erosion of excellence

Hung Cao was one of those students who thrived at top schools.

A Vietnamese refugee whose family emigrated to Northern Virginia after the fall of Saigon, Cao was a member of the inaugural class at Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology in 1985. He later attended the U.S. Naval Academy and earned fellowships at Harvard and MIT.

At Thomas Jefferson (TJ) in Alexandria, Virginia, Cao was “a skinny Asian kid” among a “nerdy hodgepodge of teenagers,” he recalls in The Washington Post. “The unifying priority for us was that we wanted to be there, and even though we collectively groaned through those difficult four years, we thrived… Within those walls, we were iron sharpening iron and, in the end, graduated with a sense of pride that has carried us through each step of our adult lives.”

Unfortunately, the merit-based admissions process that enabled Cao to earn his seat at TJ may soon be a relic.

In 2020, the Fairfax County School Board re-engineered the TJ admissions process so that fewer Asian American students like Cao are admitted to the nation’s top magnet school. Instead of a race-blind admissions test, the new hybrid system emphasizes non-academic factors, including geographic markers that act as proxies for race. Then-Sup erintendent Scott Brabrand defended the change, arguing that “TJ should reflect the diversity of Fairfax County Public Schools, the community, and of Northern Virginia.”

After the new process was implemented, Asian enrollment at the school dropped from 73% to 54%.

Cao, now a retired Navy Special Operations officer and a candidate for U.S. Congress, slams the Fairfax County School Board for prioritizing the racial makeup of TJ over academic merit.

“Discriminating against one minority group to benefit another minority group has no place in our society, and it certainly has no place in our schools,” Cao says. “What I see is an activist culture replacing competition and excellence with entitlement, and it is eroding the foundation of who we are as a country.”

Although TJ parents and Pacific Legal Foundation fought the discriminatory new admissions process and won our case at district court this year, the Fourth Circuit ruled that the new process can remain in place while the school board appeals our victory.

Which means Asian American students who would have gotten into TJ on merit will now be rejected—because of their race.

This has happened before

In 1923—almost a century ago—Harvard University proudly revealed an inclusive new admissions policy that would help the student body become “properly representative of all groups in our national life.”

Instead of focusing on test scores, Harvard’s new policy would emphasize non-academic factors like personality, background, geography, and athleticism. The committee in charge called it “a policy of equal opportunity regardless of race and religion.”

But private correspondence between Harvard alumni and officials—most notably, Harvard President Abbott Lowell—reveals the true motivation behind the policy: Harvard was desperate to limit the number of Jewish students on campus.

“The summer hotel that is ruined by admitting Jews meets its fate,” President Lowell wrote to a professor, “not because the Jews it admits are of bad character […] but the result follows from the coming in large numbers of Jews of any kind, save those who mingle readily with the rest of the student body.”

Incidentally, according to the warmth/competence study on group stereotypes, many people stereotype Jewish and Asian people similarly—in a way that evokes envy.

Under the new admissions policy, Jewish enrollment at Harvard was rolled back from 21% in 1922 to 15% in 1933. For the first time, applicants were quizzed on their backgrounds and asked to send in their photos. Amorphous qualities like “character” became the new measure of an ideal Harvard man.

And if that meant the application process wasn’t quite as meritocratic as it used to be, so be it: After all, a Harvard report reasoned, “the standards ought never be too high for serious and ambitious students of average intelligence.”

A pattern of discrimination

Now Students for Fair Admissions is bringing Harvard to the Supreme Court for “engag[ing] in the same brand of invidious discrimination against Asian Americans that it formerly used to limit the number of Jewish students in its student body,” as the petitioners put it in their brief.

Looking at notes from Harvard admissions officers, it’s impossible not to see a pattern in the way Harvard treats applicants: The school consistently employs its “personality score” to downrate Asian applicants, using language that conveniently conforms to the competent-but-cold stereotype of Asians.

“He’s quiet and, of course, wants to be a doctor,” one admissions officer notes about an Asian applicant.

Another calls an applicant “so typical of other Asian applications I’ve read: extraordinarily gifted in math with the opposite extreme in English.”

The notes call to mind a particularly brutal quote from Daniel Golden’s book The Price of Admissions, in which MIT Dean of Admissions Marilee Jones says of rejected Korean American applicant Henry Park: “It’s possible that Henry Park looked like a thousand other Korean kids with the exact same profile of grades and activities and temperament… yet another textureless math grind.” Park had been rejected from multiple Ivy League schools, despite ranking and scoring higher than his peers at the private Groton School. His parents were middle-class Korean immigrants “who scrimped to send their son to Groton because of its notable college-placement record,” The Wall Street Journal reported.

After Park was rejected, his mother told the Journal that she’d been naïve. “I thought college admissions had something to do with academics,” she said.

What we lose

As PLF argues in our friend-of-the-court brief in the Harvard case, classifying Americans by crude racial categories is deeply harmful: It perpetuates false stereotypes and degrades the dignity of individuals, who each deserve to be considered on their own merits.

It also encourages the worst kind of tribalism, in which racial and ethnic groups are pitted against each other in a toxic, envy-fueled battle.

The politicians and school board members who promote a race-based “us vs. them” mentality are doing a disservice to the communities they represent. They’re especially doing a disservice to students, who are all far more dynamic and complicated than stereotypes based on the color of their skin.

In a 2007 Supreme Court case involving a Seattle school district’s use of race, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote, “The way to stop discriminating on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” That’s what PLF firmly believes. The TJ and Harvard cases are about far more than the student bodies at those schools. At their core, these cases are about whether Americans are ready to stop stereotyping people by race—and start seeing each other as individuals. ♦

Sin #7: Sloth

California takes three years to approve wheelchair-friendly home for stroke victim

Erin Wilcox

Attorney

sloth: inactivity, carelessness

They were trapped.

David Tibbitts’ debilitating stroke in 2018 left him confined to a wheelchair. Stephanie, his wife, was having trouble moving David around the narrow hallways of their cramped 1930s-era home on the California coast.

It wasn’t supposed to be like this.

For 20 years, Stephanie and David had worked together at the whitewater rafting business that David built from the ground up. They loved their beachfront property but not the worn-down house that sat on it. Someday, they thought, they’d build themselves a new home so they could comfortably enjoy their retirement together. By 2017, they’d decided they were ready—and then David had his stroke.

It was a shock. But Stephanie is resilient. She pushed forward with plans to demolish the old house, which David couldn’t navigate independently in his wheelchair, and build a new home in its place with ramps and an open floorplan.

In March 2019, San Luis Obispo County approved the Tibbittses’ permit to build. The new home would give Stephanie a bit of peace. It would give David back a little bit of the freedom he’d lost from his stroke.

But two commissioners on the California Coastal Commission held up the project by filing an appeal. Like neighboring properties, the Tibbittses’ property has a type of seawall called a “riprap revetment” that prevents erosion. The riprap is legal under California law, but the two commissioners still wanted it removed. The other commissioners agreed: In June 2019, they found a “substantial issue” with the Tibbittses’ county-approved permit—which put the Tibbittses’ project on indefinite hold. The commission informed the couple that they couldn’t move forward with their plans until the commission could review the project at a hearing.

So Stephanie and David were stuck in the old house—with its small rooms and chronic electrical and plumbing problems—while they waited for the commission to schedule the hearing.

And they waited.

December 2020

1 year, 6 months after the commission halted the project

The email was polite but firm.

“This extraordinary delay in bringing this appeal to a close is by no means a ‘normal’ part of the land-use permitting process,” Paul Beard, the Tibbittses’ attorney, wrote to the commission. It had been, he pointed out, “[e]xactly 1½ years” since the commission found a “substantial issue” with the permit and put a halt to David and Stephanie’s plans to build a wheelchair-accessible home.

And even though California law required the commission to hold a hearing, it hadn’t even scheduled one.

“The delay has been especially stressful and harmful to the Tibbittses,” Paul wrote.

David’s health was precarious. Before his stroke, he’d always been the one to handle real estate and legal matters. Now Stephanie was trying to make sense of the California Coastal Commission’s actions on her own. “I couldn’t even talk to David about it because it would upset him,” she says.

The old house was falling apart. At one point, Stephanie heard sparking from an outlet; when she went to investigate, the whole outlet popped out of the wall into her hand. She sent Paul a photo. Surely, the California Coastal Commission would understand the need for a new house.

“My whole outlook was, ‘They can’t be this unreasonable,’” she says.

But as months went by without a hearing date, Stephanie became more and more anxious. “I had a lot of sleepless nights,” she says.

At least she had Paul Beard on her side: Paul is a partner at the private law firm FisherBroyles. He was previously a principal attorney at Pacific Legal Foundation, where he defended coastal property owners against onerous agency recommendations . He now was dealing with the commission so Stephanie didn’t have to.

A hearing to review the Tibbittses’ building plans was “long overdue,” Paul told the commission in his email, “if only for humanitarian reasons.” He asked that the couple’s project be reviewed at the commission’s next monthly hearing in January.

Brian, a staffer for the commission, responded that January wouldn’t be possible.

When Paul pushed for an explanation, Brian said that the commission’s internal deadline for the January hearing had passed. Also, the holidays were coming up. And although the Tibbittses’ project was small, it was important to the commission because of the potential precedent it could set for the commission’s regulations of other coastal properties.

“I could provide a target date,” Brian wrote, “but nothing can be considered certain, particularly when there is no specific legal deadline.”

No specific legal deadline: It was an extraordinary thing to say. He seemed to mean that the commission could delay as long as it wanted.

“Thank you for understanding,” he added.

January 2021

1 year, 7 months after the commission halted the project

Paul emailed Brian bto ask if there’d been any progress scheduling the Tibbittses’ hearing. Brian replied that the commission was targeting April.

March 2021

1 year, 9 months after the commission halted the project