Fall 2021

The Pursuit of Housing

To read more about the work that PLF is doing, visit pacificlegal.org.

When I first started in the libertarian public-interest legal movement—17 years ago!—my work focused exclusively on property rights. In fact, it was my interest in that issue that led me to start out as what I’ve referred to as a professional troublemaker (or community organizer, depending on the audience) with the Institute for Justice way back in 2004.

What’s struck me over my more than a decade and a half of work helping place constitutional limits on government power is that we sometimes do our side a disservice by utilizing esoteric legal language or overly philosophic terminology. When I’d give talks about stopping governments from taking property through eminent domain—not for public uses like roads or schoolhouses, but for private ones like condominiums or shopping malls—I’d try to catch myself in discussing the concept of property rights, or at the very least expand on what I meant beyond the phrase.

Property, of course, doesn’t have any inherent rights. We naturally have rights in property. Debates about property rights, then, aren’t about property. They are about people.

And over the course of human history, the most important property we have tended to own is our home.

It’s where we celebrate and grieve, laugh and play, break bread, and grow. There’s both intrinsic and real value, the latter of which often serving as the means for us to do other things in life, like educate our children or build a business.

This issue of Sword&Scales is a nod to this fact—and the sad reality that government rules often stand in the way of us experiencing all these things. We’re telling just some of the stories of the folks who’ve been caught in the crosshairs of bad policy, especially on housing, and how that’s led us to where we are today, a place where the creation of new homes is costly, difficult, and sometimes simply prohibited. These are the real-world outcomes of the housing crisis.

You’ll notice that every article shares one author: Jim Burling. After decades of being on the front lines of many important battles vindicating our ability to own and use property, he’s our resident expert. These stories and more are the subject of an upcoming book. And speaking of front lines, beyond our scholarship, we’re also moving forward with plans to significantly amplify our litigation on rights in property and legalizing the production of housing, focusing initially on accessory dwelling units (or ADUs).

After all, how we treat property—ourselves—is ultimately up to us. Pacific Legal Foundation’s charge is to ensure it’s with respect.

Steven D. Anderson

PRESIDENT & CEO

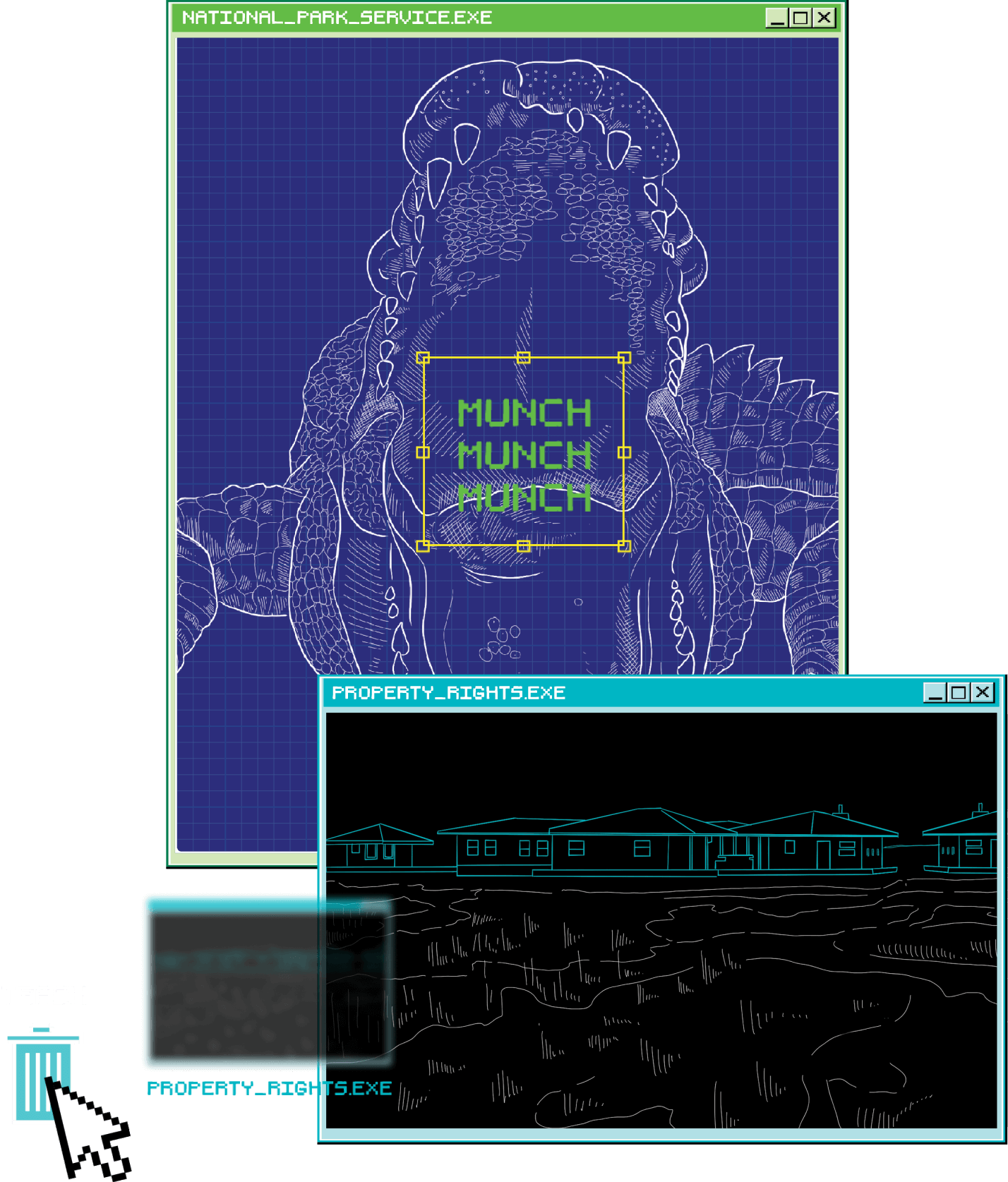

A flood in the Everglades

Brittany Hunter

Social Media and Editorial Writer

Jim Burling

Vice President of Legal Affairs

BORN AND RAISED in New York, Gilbert Fornatora’s family often vacationed in Florida, offering them a warm escape from the brutal East Coast winters. It was during these cherished trips of his boyhood years that he became taken with the Miami-Dade County region.

But his interest in the area wasn’t due only to its scenic landscapes and warm sunshine. In the 1950s and 1960s, when Gilbert had become an adult, the investment potential in the western part of the county was expected to boom.

His father had several friends in the real estate world who specialized in the buying and selling of acreage, rather than residential properties. It was through these friends that the family first became aware of the investment opportunities in the area.

The elder Fornatora poured himself into researching the land’s potential, becoming ever more certain that this was the path for his family to make some real money to secure their financial future.

In the days before 401(k)s, people had to save for their retirement in other ways. Buying land was among the most popular means of preparing for the future.

Set on pursuing this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, Gilbert’s dad began encouraging him to get in on the investment while the getting was good. He frequently told Gilbert that there was “no new ground to be manufactured,” so putting their money into land was a no-brainer.

He followed his father’s advice, and the Fornatoras began slowly buying up acreage in western Miami-Dade County, putting their retirement plan into action.

The 480 acres of land the family ended up purchasing over time bordered Florida’s Everglades National Park. Being so close to federally protected land, the area had always been subject to strict regulations. As Gilbert explained, when it came to this tract of land, elements of the federal government always “loomed in the background.”

IN THE 1970s, the looming government threat became real.

Gilbert’s dad and other property owners in the area had heard rumors that the National Park Service (with support from many environmental groups) wanted to expand the boundaries of Everglades National Park. While at first there was no grand announcement, or press conference, the actions of the Park Service proved the property owners’ fears were true.

In the early 1970s, the National Park Service gave the county funds to conduct a study on the health of the watershed in the area.

This was not the first time such a study had been commissioned. Gilbert’s father had noticed a pattern: whenever the National Park Service wanted to justify violating property rights in the area, it would literally open the floodgates, purposefully flooding the border of the property line and the Everglades. The federal officials would then go to the county governments and say “Look! The land is under water!” and some sort of intervention would ensue.

Gilbert’s dad knew that for most of the year, the land was fine—it was only when federal entities intervened and allowed the flooding to happen that any potentially harmful effects would occur.

So it was really no surprise to Gilbert’s father when the feds went to Miami-Dade County officials and offered to fund a study about the health of the watershed.

It was the Fornatoras’ belief that the Park Service’s goal with the study was to conclude that there was too much development in the area to maintain healthy water levels, in order to put the kibosh on further development. Without development, the land’s value would not appreciate, putting a damper on the family’s retirement plans.

The results of the study concluded that the watershed was perfectly healthy for the current population and developments. But bureaucrats on a mission are not easily stopped.

DESPITE THE STUDY SHOWING THAT NO ZONING CHANGES WERE NEEDED, in 1975, Miami-Dade County enacted a comprehensive plan that down-zoned this property so fewer buildings could be built on the land. Fewer development options mean less valuable land.

Then, just six years later in 1981, the federally funded land commission responsible for advising the county planners had revisited the plan and recommended that zoning be restricted to one dwelling per 40 acres.

These limitations significantly reduced the value of the Fornatoras’ and their neighbors’ property even further.

With the National Park Service working so closely with county officials, the Fornatoras could not help but think that the stage was being set for the federal government to take the land without having to pay just compensation for its use.

Even with the surrounding land values now diminished, the Park Service still needed congressional approval before expanding Everglades National Park. In 1989, Congress authorized the expansion, hammering the final nail in the coffin of the property owners’ dreams.

After congressional approval, the Park Service began seizing the surrounding properties at pitiful prices to expand the park.

THE COUNTY LAND COMMISSION sent each property owner a notice explaining that the process of condemnation had begun. Each owner was made a lowball offer for their once-valuable land.

Gilbert had watched his father fight this plan every step of the way. And when his father passed away in 1991, he followed in his footsteps, fighting back in court.

He sued the Park Service, claiming that the government wasn’t giving him fair compensation for his land. Others followed suit.

Gilbert was supposed to be the first Everglades case heard in court, but it got postponed, rescheduled, then postponed again.

He later found out that his case kept getting pushed back because the Park Service was going after those landowners without legal representation before coming after the ones with attorneys.

It was going to be easier to take from the property owners without legal representation. Understanding this all too well, the Park Service grouped the property owners together: those with attorneys were in one group, and those without were in another.

Those who had been able to secure legal representation were excluded from the first round of land confiscation.

This was an especially cunning move on behalf of the Park Service. Much of the property in question was owned by immigrants and blue-collar farmers, many of whom were just trying to live their lives in peace. They weren’t well-versed in the law, nor did they have the means to hire attorneys to fight for them.

Many of the family’s neighbors were also Cuban immigrants who had fled their oppressive government in search of freedom and prosperity. The property surrounding the Everglades was the only land they could afford in the Miami area. The privilege of owning property not only gave them a sense of independence they were not afforded in Cuba, but it also gave them the opportunity to start over and begin building their American Dream.

Unable to fight back, many of Fornatora’s neighbors were an easy target. They were ultimately offered minuscule amounts of money for their land—about $2,500 for three acres.

Without any recourse available to them, they took what was offered and said goodbye to their property.

By going after those without legal representation first, the Park Service was able to set a precedent, valuing the land at a much lower rate than it was worth.

When it came time for Gilbert’s case to be heard, the Park Service was able to lowball him, pointing to the payouts given to his neighbors in the first round of landgrabs.

GILBERT WASN’T READY to give up just yet. He gathered several letters from federal agencies to Miami-Dade County officials to present in court. The documents urged county planners to restrict development, in a “Federal-State effort” to preempt “numerous and piecemeal legal confrontations” with property owners.

But no matter how much evidence he supplied, the court continued to claim that there was no real proof to confirm the Park Service’s “primary purpose” was to devalue the land.

In cases of this nature, the government entity in question only needs to state what their primary purpose is. As can be expected, the Park Service denied that its primary purpose was devaluing the land, placing the burden of proof on Gilbert.

As the Eleventh Circuit Court wrote in its decision, “A landowner must show that the primary purpose of the regulation was to depress the property value of the land or that the ordinance was enacted with the specific intent of depressing property value for the purpose of later condemnation.”

The court’s main stance was that Gilbert could not prove that devaluing the land was the “primary purpose” of the Park Service’s plan. The court did concede that it may have been a small part of it. In fact, the Eleventh Circuit Court’s opinion even acknowledged that his criticisms were valid, and that the primary purpose rule often gives governments an incentive to mask their true motives behind zoning restrictions. But the court also acknowledged that it was highly unlikely that the government would ever admit this as their primary purpose in passing the regulation.

The National Park Service, via the county government, had managed to use the power to rezone the land in order to devalue the property and expand the national park. But doing so violated constitutional property rights protections.

Adding insult to injury, throughout the whole ordeal the government’s attorneys treated Gilbert like a criminal. When asked about the experience, Gilbert says he “doesn’t have too many good words” to say about the lead attorney representing the government. He remembered the attorney as “aggressive and easy to dislike.”

As Gilbert continued his fight against this unjust practice, Pacific Legal Foundation joined the fight, helping him try to get his case heard before the Supreme Court.

As former PLF attorney Steven Geoffrey Gieseler stated at the time, “When government takes property, the Constitution requires compensation that is just, not merely what the government thinks it wants to pay.”

He continued:

“Federal manipulation of the eminent domain process prevented Gilbert Fornatora from being justly compensated. We’re asking the Supreme Court to review this case in order to halt eminent domain abuse by federal officials, and to uphold the just compensation principle for property owners all across the country.”

The Fifth Amendment to the Constitution protects individuals from having their property seized without just compensation. It states, “No person shall be…deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.”

Yet the Park Service was doing everything it could to avoid giving just compensation to the landowners.

Unfortunately, in 2009, decades after the debacle had begun, the Supreme Court announced that it would not hear Gilbert’s case.

Without the primary purpose standard being met, Gilbert did not have a legal leg to stand on. And this prevented any meaningful discussion from taking place.

The case died there.

Conventionally speaking, the Fornatoras’ story did not conclude with a victory. In the end, more than 1,000 property owners had their land taken from them without just compensation.

While the family never necessarily expected to live on the land, they knew it was a great long-term investment that would appreciate in value. In fact, Gilbert had dreams of turning some of his land into a golf course, once the time came for him to retire.

To say this experience soiled Gilbert’s belief in due process would be an understatement.

The Fornatora family was never able to recover their losses. They were forced to sit by and watch as their retirements dissolved into nothing.

While Gilbert has spent years trying to forget the unpleasant legal proceedings, he has no regrets. He “cannot accept that somebody should steal a person’s property. And they were stealing my property.”

Defenders of individual rights may not always be able to slay Goliath, but we need people like Gilbert Fornatora willing to stand up and fight. ♦

Béton brut

Joseph Kast

Creative Manager

Jim Burling

Vice President of Legal Affairs

CAN SOCIETY BE designed? Can an expert engineer alleviate people’s pains and struggles with a good-enough central plan and blueprint?

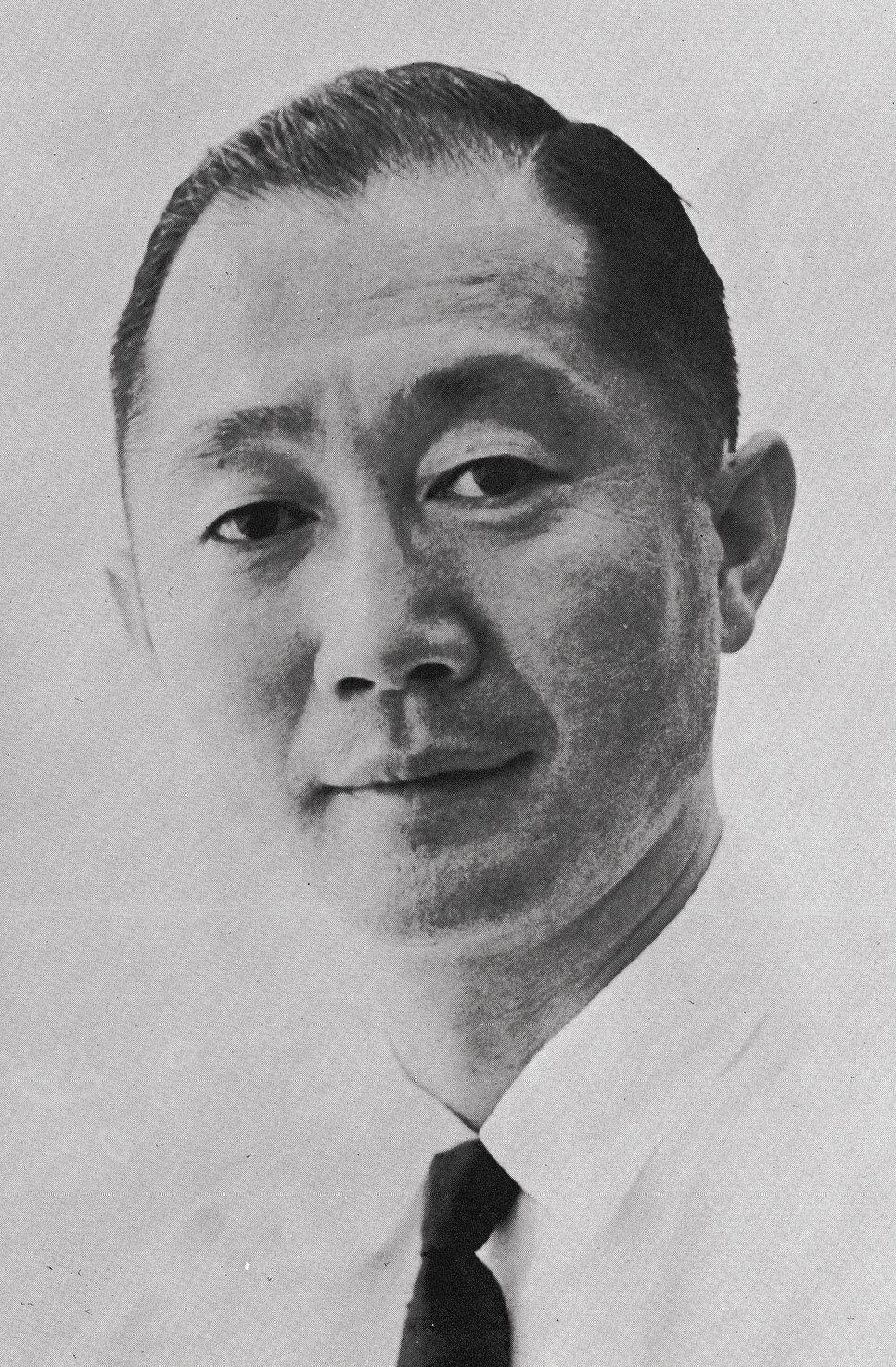

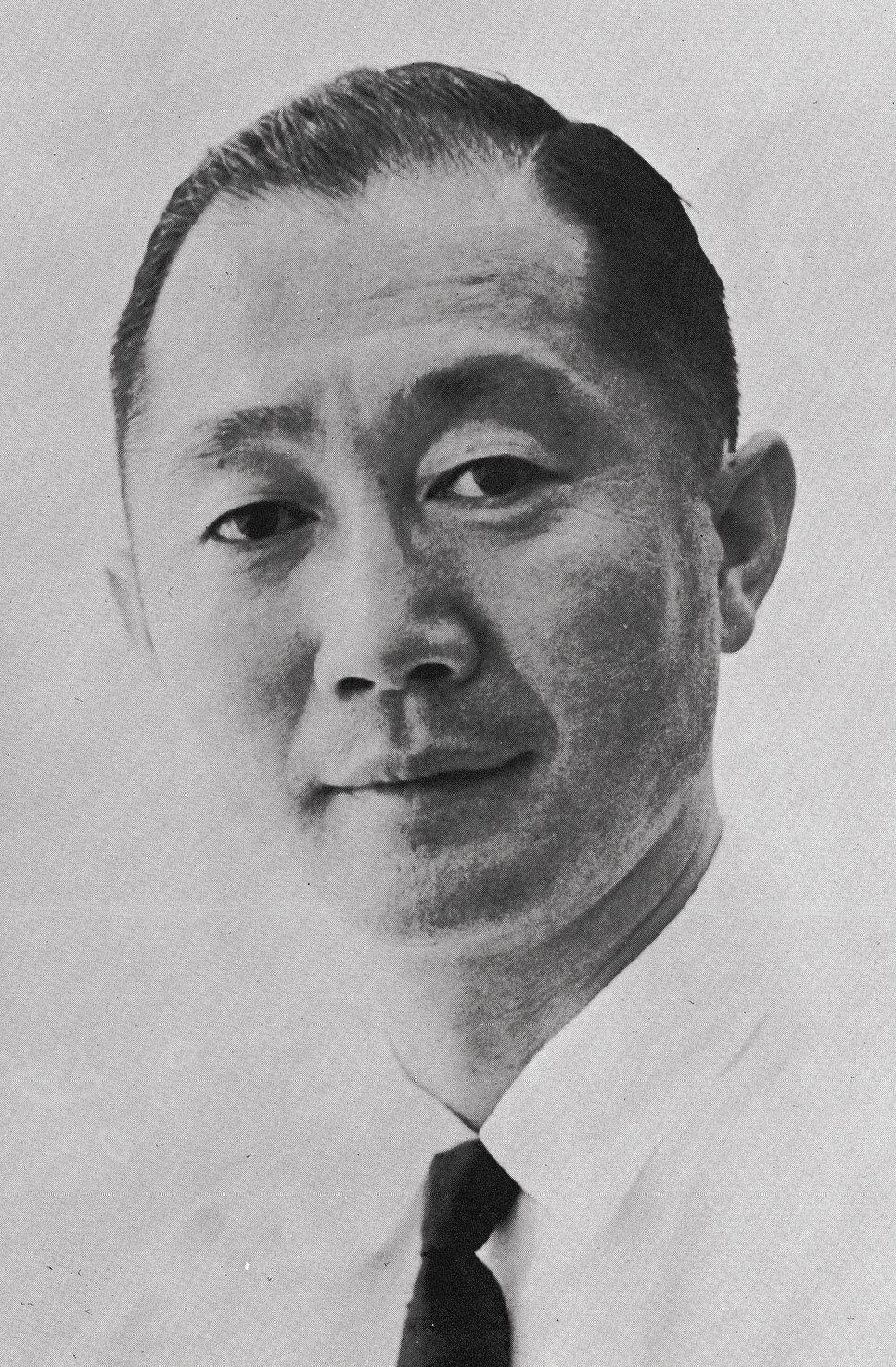

Minoru Yamasaki thought so.

Yamasaki was one of America’s most well-respected architects in the 20th century and was a member of the school of thought that people’s human nature could be improved (whether those people needed or wanted improving) by a properly planned building surrounding them.

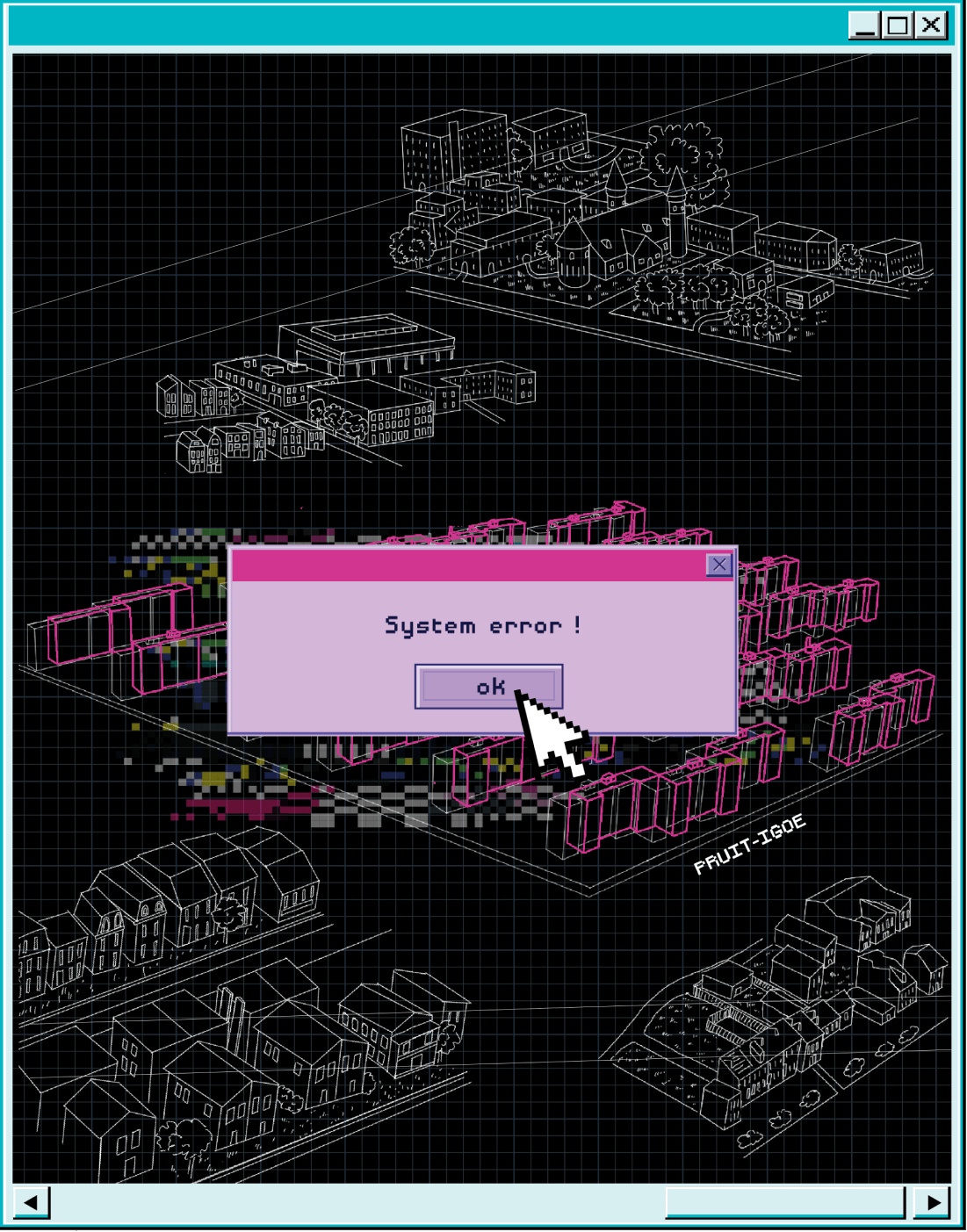

Yamasaki got to test his theory by designing the public housing complex that promised to be a template for all public housing going forward. The complex, St. Louis’ Pruitt-Igoe, was made possible by post-war New Deal housing and urban development programs. And like many New Deal initiatives, Pruitt-Igoe was guided by the idea that good intentions, centralized planning, and strong government power would progress society more than protecting people’s rights or personal choices.

Pruitt-Igoe, and Yamasaki’s designs, were sold as the solution to poverty, crime, and housing in America’s major cities, but within just a few years, the complex would show the dangerous consequences when government planners take away people’s liberties and homes.

YAMASAKI’S CHILDHOOD READS like a Horatio Alger novel. His parents emigrated from Japan and settled in Seattle at the turn of the century. His father worked three jobs to provide what he could for the family, but it was a hand-to-mouth existence nonetheless. Seattle was not a great place to be Japanese, and Yamasaki never forgot his bitter memories of being denied access to pools and harassed at theaters.

He put himself through undergrad at the University of Washington by doing grueling work at a salmon canning plant during his summers. He’d work anywhere between 70 and 120 hours a week. The pay was $800 a month in today’s dollars.

Minoru Yamasaki

But the work paid off and Yamasaki showed true promise in architecture. He suspected the anti-Asian sentiment in Seattle would stifle opportunity, so he moved to Manhattan with all of $40 in his pockets. He enrolled in a master’s program in architecture at NYU and wrapped dishes for an importing company to pay his way.

But what a time to study architecture! This was the high modernism era: Walter Gropius, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Le Corbusier were rethinking everything. Breakthroughs in glass, steel, and concrete created new possibilities.

Le Corbusier, or Corbu as he was known, was a major influence for Yamasaki. Corbu was perhaps the most extreme of the high modernists. He had unyielding faith in the power of rationalism and efficiency to improve every facet of society. He believed homes should be “machines for living.” The master planner could create literal utopias by exerting his expert will from the top down.

And Yamasaki was eager to implement Corbu’s ideas in American cities. After Yamasaki graduated from NYU, he was officially an architect and joined the firm Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, best known for designing the Empire State Building, among many other towering buildings in Manhattan. After World War II ended, he worked at a few other firms before starting his own firm in 1949.

Yamasaki had plenty of experience. What he didn’t have was a signature building. But that would come soon enough.

HIGH MODERNIST ARCHTECTURE MET a perfect ally in the postwar urban renewal movement, which shared the same “raze it all and start from scratch” ethos. Slum clearance and urban renewal sprung up across the U.S. after the Supreme Court issued its opinion in Berman v. Parker in 1954, a decision that was breathtaking in its surrender to government power.

A Washington, D.C., department store owner sued the DC Redevelopment Land Agency after the agency began proceedings to take the department store through eminent domain, demolish it, and sell the land to a private developer. The government claimed it was solving “blight,” but the plaintiff argued the government was simply taking private property and giving it to another private party.

The Supreme Court sided with the government in a major loss for property rights. The decision effectively expanded governments’ power to invoke eminent domain from “when strictly necessary for the public good” (say, an airport) to something like “whenever politicians think it’s best,” a ripe opportunity for cronyism and corruption.

The Berman decision also came on the heels of the Housing Act of 1949, which vastly expanded the federal government’s involvement in housing. The main elements were federal financing for slum clearance and urban renewal, expanding mortgage insurance to increase home ownership, and the construction of public housing units.

Between the Berman decision, a windfall in federal money for interventionist housing policies, and an ascendant architectural movement with visions of creating utopias through buildings and design, all the ingredients for a grand-scale government failure were about to erupt.

POSTWAR ST. LOUIS was ready for a makeover; one historian said it resembled “something out of a Dickens novel.” The city’s population had grown significantly and local leaders assumed it would continue to grow at the same clip for decades. They feared tenement housing would overtake the central business district. Even though local voters had rejected a proposal for high-density public housing in 1948, with federal money now so abundant, large housing projects were hard to resist.

Joseph Darst, the Democrat mayor of St. Louis, didn’t need convincing. Nor did Republican state officials. The bipartisan consensus was that radical action was needed for the city. Darst put the case bluntly: “We must rebuild, open up and clean up the hearts of our cities. The fact that slums were created with all the intrinsic evils was everybody’s fault. Now it is everybody’s responsibility to repair the damage.”

Darst and other city officials began what author Jeff Byles calls a “multipronged assault on five square miles of the city.” Soon demolition crews were eradicating entire neighborhoods. The neighborhood of Mill Creek Valley alone saw the demolition of some 5,000 buildings, including 43 historic churches.

While city leaders considered these neighborhoods to be irredeemable slums, not everyone agreed, and many residents had been happy to call the demolished neighborhoods their home. Former Mill Creek Valley resident Gwen Moore said, “My memories are very pleasant, and I remember being traumatized when we were told that we had to move.”

Race was a factor in city leaders’ motivations. Part of the reason St. Louis was expanding was that many Black southerners were moving to the city from the South to escape Jim Crow. Meanwhile, whites were leaving the city in droves. For many Black Americans, urban renewal seemed like a containment effort. Black author James Baldwin famously changed (corrected) the term to “Negro removal.”

The flagship development plan to replace the razed neighborhoods was for a high-density public housing project called Pruitt-Igoe, named after two St. Louis heroes: Wendell Pruitt, a Tuskegee Airman, and William Igoe, a former congressman. The Pruitt buildings would be for Blacks, and Igoe for whites. But the project, which launched in 1954, had to lose this segregated design conceit after the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which ended the “separate but equal” doctrine.

Officials had a general idea of what they were looking for in the project’s design: tall, modern buildings that would both accommodate a growing metropolis and end impoverished conditions in St. Louis’ tenements. Construction was funded by state and federal money, but the complex was intended to be self-sustaining from the working-class residents’ rent.

What they didn’t have yet was an architect up for the challenge. For that, city leaders selected a promising young architect named Minoru Yamasaki.

YAMASAKI’S INITIAL PROPOSAL was a blend of Corbu and his own ideas about how to improve people’s lives through architectural design. From Corbu, he drew heavily from the unrealized Ville Radieuse: rows of high-rises, threaded by a “green river” of foliage and playgrounds. Most important was Corbu’s economy-of-scale idea—fit as many units as possible into the buildings.

Yamasaki’s initial proposal included a mixture of two-story walk-ups, mid-rises, and widely spaced 11-story blocks. He incorporated a new type of “skip-stop” elevator. These stopped only on every third floor, which both saved room for more units and encouraged a sense of community engagement by forcing residents to interact more. Or so he hoped. The hallways were wide and “streetlike,” again to mimic a sort of town square inside the high-rises.

The design was widely praised. An Architectural Forum article titled “Slum Surgery in St. Louis” called Yamasaki’s proposal “the best high apartment of the year.” City leaders boasted about the high-rises, claiming that these slum residents would now have more magnificent views of the city than its richest residents. Tall, modern buildings that granted light and fresh air, where there were once polluted slums.

While Yamasaki’s designs were adjusted by St. Louis officials (they scrapped the smaller buildings for 33 high-rises), Pruitt-Igoe was the culmination of many turn-of-the-century progressives’ plans for government’s top-down role in every aspect of society. But like many of the New Deal plans and programs, the promises of Pruitt-Igoe were only truly viable on paper, and the utopian dreams of Pruitt-Igoe began shattering before the first high-rise was even built.

CITY PLANNERS THOUGHT St. Louis was undergoing a population boom. It wasn’t. Amity Shlaes, in her book Great Society, explains how local authorities were convinced “St. Louis would grow and sustain its citizens. Instead, in part because of other interventions by authorities, the city shrank. Economies, it turned out, were like humans. They made choices.”

The Housing Act’s provision of government-backed mortgage insurance meant suburban housing was cheap and getting cheaper. So were cars. President Eisenhower’s interstate highway project, which (arguably) began with the paving of I-70, connected St. Louis with the blossoming suburbs of St. Charles just across the river. Despite the decision in Brown v. Board, white families were taking that same FHA money that funded Pruitt-Igoe and buying homes in the suburbs, and many jobs went with them.

This fundamentally changed the city. De facto segregation soared; the city shrank and suburbs swelled. If St. Louis’ leaders realized their assumption of continued economic growth and population growth was wrong, they kept it to themselves.

It quickly got worse from there. Planners expected the working poor to live in the complex. Instead, many unemployed families took the apartments, which meant—because families receiving welfare paid the lowest rents—the rent revenue wasn’t enough to sustain the building.

Also, under Missouri’s welfare laws at the time, you could receive welfare only as a single parent. This left many mothers and fathers with the grim options of staying together without the state benefits, or separating in order to receive benefits. Many fathers left their families to search for work wherever they could find it. They often didn’t return. Soon Pruitt-Igoe was mostly populated with large, single-parent families. The lack of fathers in the building (and social workers ran regular checks to ensure dad really wasn’t living there) had dangerous ripple effects for Pruitt-Igoe children. Crime quickly became common, and children joined gangs, vandalized and damaged the buildings. Maintenance workers had trouble keeping up and occupancy dropped rapidly.

The day President Lyndon Johnson gave his famous “Great Society” speech in 1964, residency in the complex hovered around 25%.

And what of Yamasaki’s innovative skip-stop elevators? His wide hallways? Did they foster a sense of community as he intended? Amity Shlaes paints a bleak picture:

[The] elevators… were muggers’ traps. Poor maintenance meant the elevators often jammed, leaving gangs’ victims in with them for long extra minutes. The gangs lurked in the halls and made tenants “run the gantlet” to get to their doors.

Young men threw bricks and rocks at windows and streetlamps; the activity was a regular sport. There were no good playgrounds. Because there were no toilets on the ground floor, children had accidents there, and the elevators gradually became public toilets. The community area was a sorry joke; its only function ultimately was as a place for collecting Housing Authority rents. No one seemed able to stop the decay.

ST. LOUIS QUICKLY realized that Pruitt-Igoe was a problem. But it was unclear who, if anyone, could fix it. The federal government, the St. Louis Housing Authority, the state, and the City of St. Louis itself all shared responsibility for the complex. When a problem belongs to everyone, it belongs to no one.

Within five years of its launch, Yamasaki was regularly apologizing for his role in the project. Though the final design of the complex differed from his original vision, he came to question the core assumption behind the project: that people’s lives could be effectively engineered through urban design. He expressed regret for his “deplorable mistakes” with Pruitt-Igoe. By the 1950s, he was giving eloquent speeches about the “tragedy of housing thousands in exactly look alike cells,” which “certainly does not foster our ideals of human dignity and individualism.”

To the Detroit Free Press, he put it more simply: “Social ills can’t be cured by nice buildings.”

By the early 1970s, the 33 concrete tombstones lining St. Louis’ skyline were a cautionary tale for utopian housing schemes. It was a den of crime and misery, rather than anything anyone could call home. When the decision came to demolish it, occupancy was only 10%.

The day the demolitions began at Pruitt-Igoe, architectural historian Charles Jencks declared the death of high modernist architecture and its grand assumptions: “It was finally put out of its misery. Boom, boom, boom.”

Three towers were demolished in 1972. The last tower finally came down in 1976, leaving nothing of Pruitt-Igoe behind.

YAMASAKI’S FATE WAS permanently tied to Pruitt-Igoe.

Throughout his long career, he had successfully built airports, consulates, convention centers, and college buildings. He designed the World Trade Center with its iconic Twin Towers and even graced the cover of TIME magazine for his impact on American architecture. But Pruitt-Igoe had damaged his reputation, and it took a toll on his later work. Toward the end of his career, his buildings became muted and stylistically indistinguishable. When he died in 1986, his New York Times obituary included a section on Pruitt-Igoe under the subheading: “One Big Failure.”

But Yamasaki was not wholly to blame for the failure of Pruitt-Igoe. Neither were Corbu’s ambitious ideas, flawed as they were. The Pruitt-Igoe project was doomed before Yamasaki’s proposal was even submitted.

It was doomed when St. Louis politicians uprooted thousands of St. Louisans from their homes and forced them into massive concrete towers that they hadn’t asked for. The design, which the residents had no say in, was totally alien to them. “There was nothing soft in Pruitt-Igoe,” one former resident remembered. St. Louis’ planners and politicians thought they could treat citizens like guinea pigs in a grand social experiment.

Pruitt-Igoe being demolished

Put bluntly, the road to hell is paved with government interventions.

The tragedy of Pruitt-Igoe for Yamasaki was what it did to his legacy. While he began his career subscribing to the high modernist and progressive mentality of the possibilities of top-down control, after he saw the error of his thinking, he evangelized against it. But Pruitt-Igoe will always be the stain on his incredible portfolio of beautiful buildings.

The tragedy of Pruitt-Igoe for society is how it ruined people’s lives. Thousands of poor, blue-collar workers and transplanted southern Black families became victims of Pruitt-Igoe’s failures. But despite the poverty, crime, and human destruction Pruitt-Igoe caused, not one government official was held accountable for its failings, and Yamasaki was the only one whose reputation suffered.

In the end, the lesson Yamasaki took away from Pruitt-Igoe’s failure is prescient of the eternal failure of government policies that violate individuals’ rights: “In spite of my vision for how architecture could genuinely improve the lives of people, it seems that certain real social and economic conditions make this impossible.”

Government can’t create utopias, and every time it tries, people’s rights—and many times their homes—get destroyed. ♦

The forever job

Kathy Hoekstra

Development Communications Officer

Jim Burling

Vice President of Legal Affairs

LEGEND. Icon. Renegade. Pioneer

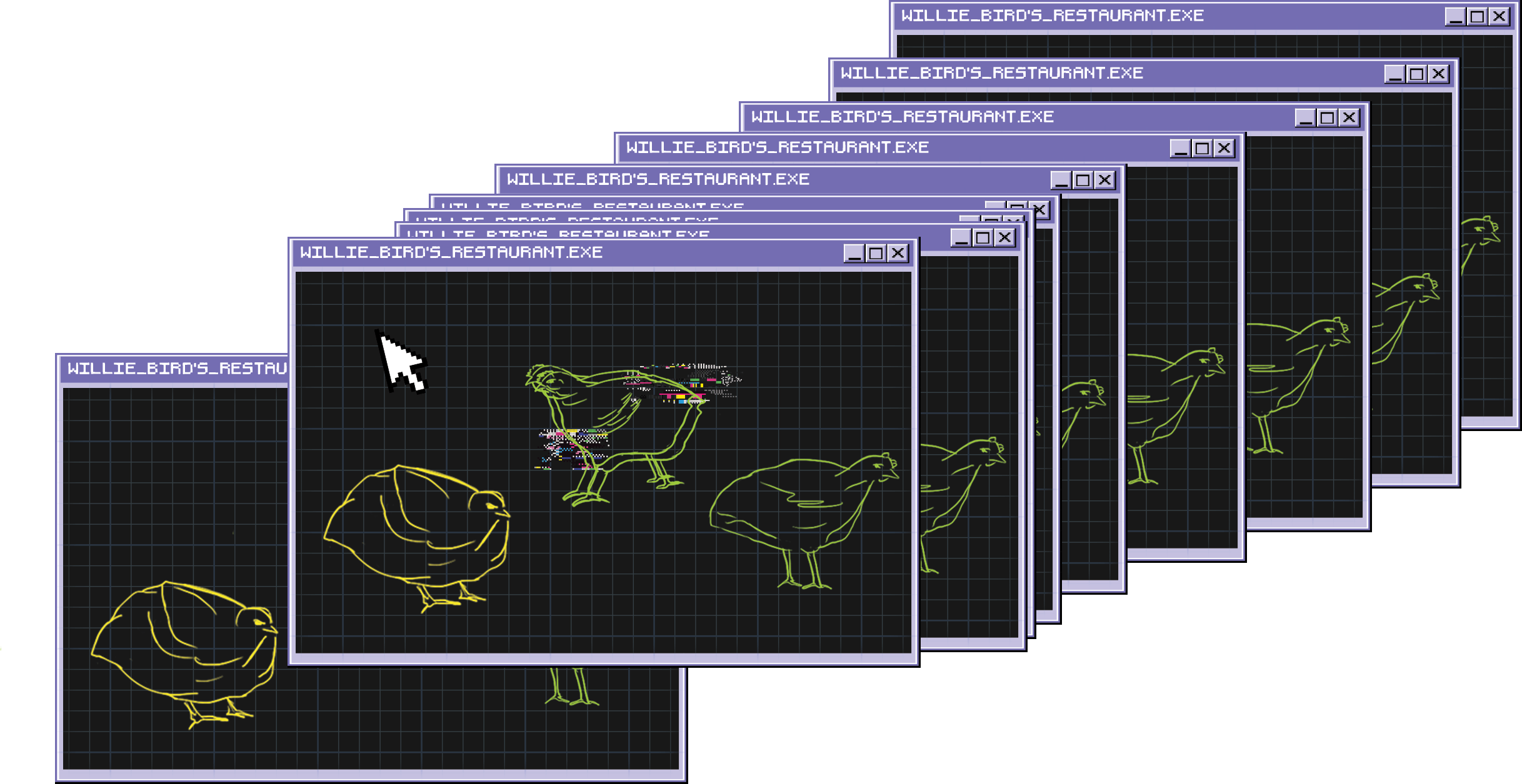

The sobriquets Willie Benedetti collected during his lifetime are as numerous as they are grand.

As the spark that ignited Willie Bird, the famous free-range turkey enterprise of more than 40 years, they were also deserved.

To his sons, Arthur and Arron, however, Willie was simply “Pops”—an affectionate nickname that perfectly fits the tight family ties that sustained them in a showdown with government regulators.

The legal battle outlived Willie, but thanks to his sons, it is settled—for now. Yet the Benedettis’ saga to defend the family’s land from bureaucratic control is a reminder that individual liberty requires eternal, relentless vigilance.

Willie Benedetti on his farm

“Here comes the Willie Bird!”

THE BENEDETTI NAME became intertwined with poultry in 1902, when Willie’s grandparents emigrated from Switzerland to Petaluma, California, and started a chicken ranch.

The family lost the chicken ranch, along with everything else, in the stock market crash of 1929. The children, Alvin and Walter, revived the Sonoma County bird business after World War II, selling fertile turkey eggs to hatcheries around the country.

The pivot from eggs intended for breeding to turkeys meant for meals began in 1963 as a Future Farmers of America project of Walter’s son, Willie. The 14-year-old Sonoma Valley High School freshman hatched, raised, and processed close to 500 turkeys for sale as holiday dinners.

Thus, a legend also was hatched; its lore, well-documented. While small details may differ in each retelling, two elements of Willie Bird’s origins remain consistent and undisputed: Willie’s dad wasn’t enthusiastic about the project because of the extra work, so his mom, Aloha, helped their son buy the eggs and keep them hidden until they hatched; and, when Willie brought turkeys into John Kings Beauty Salon, the Petaluma beauty shop where his mom worked, the beauticians would sing in chorus, “Here comes the Willie Bird!” (Or “Willie Bird, spread the word!”—depending on the storyteller.)

The name stuck, and with help from his brother, Riley Benedetti, and their cousin, Rocky Koch, Willie began raising Willie Bird turkeys for holiday dinner tables across the nation.

Willie’s larger-than-life presence and likeability were natural fits for the budding poultry entrepreneur. So was loyalty. In 2009, Willie went on an Alaskan boat adventure with some longtime college friends, one of whom kept an online journal and wrote:

The guys met at Cal Poly and have kept in touch over the last 42 years. In college, we all wanted to be Willie’s roommates because his family had a turkey ranch and we knew we would eat well. And we did, especially if you liked Thanksgiving dinner every day! During Thanksgiving and Christmas, we all would travel to Petaluma, CA and help Willie butcher fresh turkeys which folks would drive miles to buy.

In its prime, Benedetti’s operation raised 85,000 turkeys a year and became famous as well for smoked products. Their huge barbecued turkey legs were legendary at street markets and county fairs.

Dubbed the “king of a turkey ranch-to-table empire,” long before the birth of the farm-to-table movement, Willie’s 1990s expansion into Williams Sonoma mail-order turkeys was considered cutting edge. From a 1997 Thanksgiving feature in the LA Times:

Indeed, Willie this year has produced the Tiffany of turkeys—the world’s first $100 hen. At least, that’s what a select cadre of Williams Sonoma catalog customers paid for the privilege of having one of these 16-pound to 18-pound gilded gobblers delivered to their doorstep Tuesday, in time for the Thanksgiving holiday. Mind you, this is just the freshly slaughtered beast for the feast—unadorned, uncooked and unaccompanied by trimmings.

The gourmet turkeys have been dished up near and far, from the popular Willie Bird’s Restaurant in Santa Rosa, California—a Guy Fieri favorite—to the nation’s upscale hotels and restaurants, as well as the White House. Even the Queen of England has dined on a Willie Benedetti smoked duck.

“He loved his business,” said his son, Arthur, who lives in Petaluma.

Willie also loved his family and he loved living in his log cabin on the beautiful Marin County ranch he bought in 1972. “God’s country,” he called it. The property’s 267 acres provided plenty of room to build another home for succeeding generations of Benedettis.

After all, thought Willie, he wasn’t going to farm forever. He looked forward to retiring one day, surrounded by his children and grandchildren. For Willie, there was no better place for that to happen than on his own land.

Marin County had other plans.

“What kind of law forces a man to keep farming?”

LOCATED WITHIN CALIFORNIA’S Coastal Zone, Marin County is among more than 90 local governments subject to California Coastal Act land use regulations and their enforcers, the California Coastal Commission (CCC).

Development throughout the Coastal Zone is governed by local governments, albeit under the heavy hand of the CCC. Cities and counties are required to come up with their own land use plans (LUPs), which become enforceable only after CCC certification.

The CCC certified Marin County’s first LUP in 1982. Nearly three decades later, the county decided it was time for a major overhaul.

That was 2008. In May of 2017, after years of negotiations with the CCC—and finally, the agency’s blessing—the county finalized a new LUP.

That same year, as the ink dried on the revamped plan, Willie Benedetti was approaching his 68th birthday with an eye toward retirement and a home for his son, Arthur.

Willie was already prepared for government red tape. Building a second home on one’s property in Marin County falls under CCC purview, which means landowners must meet conditions dictated by the county’s LUP. And for more than 35 years, the plan allowed one additional home per 60 acres of agriculturally zoned property—like Willie’s.

The only catch is the landowners must get a government permit, which Arthur admits is no easy task in California.

“You have to spend $60,000 and two years of your life just to get the permit,” he says.

The reward of having his family close vastly outweighed the cost, so Willie applied for a permit, only to learn it came with a far greater price tag: his rights.

The county’s new LUP included a “forced farming” mandate for building permits. That is, permit approval requires that current landowners—and all subsequent landowners—must remain “actively and directly engaged” in agriculture in perpetuity.

“I don’t see why the county thinks they can tell me I have to keep working just because I want to do something that farming families have done for as long as there has been farming: build a home for the next generation,” Willie said at the time.

Marin County reasoned that forcing farmers to farm forever would keep the scenic, rolling hills and fields from becoming a boutique getaway for the Hollywood crowd.

With his characteristic bluntness, Willie called it as he saw it.

“What kind of law forces a man to keep farming? There are understandable regulations and then there is BS,” he told a reporter.

He was absolutely correct. Willie’s property had been a family farming operation for 45 years prior, and existing zoning laws were more than adequate in preventing the very development feared by county bureaucrats—only a dozen houses were built in the area in the past 50 years, and Willie’s nearest neighbor was five miles away.

Instead, the regulation weaponizes building permits to force the landowners into one career from which they can never retire.

Arthur echoes his dad when he insists the forced farming mandate has nothing to do with the environment or farming, and everything to do with restricting liberty and property rights.

“All these government actors want is control,” he says. “They wanted to control everything that Pops did.”

Willie wasn’t about to let government control his right to choose when and how to work. And he had U.S. Supreme Court precedent on his side.

Pacific Legal Foundation’s 1987 Supreme Court victory in Nollan v. California Coastal Commission made it clear that government cannot use land development permits to coerce applicants into making large and unrelated property rights concessions without compensation.

In July 2017, and represented by PLF free of charge, Willie sued Marin County and the CCC in state court to invalidate the LUP forced farming provision as an unconstitutional condition on his right to use his property as he wishes.

Willie died the following year. His sons inherited the property, but both Benedettis are plumbers. While Arthur had been actively involved in the family’s companies, Arron had no desire to do the same. Either way, the sons faced the same forced farming mandate if they wanted to build homes.

For Arthur, taking up his dad’s fight wasn’t just principle. It was personal.

If not for the unconstitutional land use provision, he’d have been living right next to his dad when stomach cancer struck.

“I’d have been out on the ranch up until he died,” Arthur says. “I live in Petaluma. He lived 45 minutes to an hour away in Valley Ford. I’d have been there to care for him all the time.”

In February 2020, the county and CCC backed down from enforcing the rule—a legal victory with an asterisk. Marin County Superior Court finalized a stipulated dismissal in which the county agreed it will not apply the mandate to anyone unless further action on the plan takes place.

“It’s what we wanted and Pops would be happy to know that it’s finally over, but it would have been nicer if he was there to enjoy it with us,” says Arthur. “He’d have a big grin on his face, a stogie in his mouth, and a vodka and cranberry in his hand, and he’d have laid back and laughed and said, ‘Aha! I knew it would take a long time but we got ’em!’”

The Willie Bird legacy may now be in the rearview mirror, but as long as forced farming is a threat, Arthur and his brother stand ready for battle.

“Why buy a piece of property and own it if you can’t do anything with it or if you’re constantly being hounded on what you can and can’t do with it?” he asks.

It soon became time to move on. Arthur sold the family’s restaurant in 2019, and in 2020, he closed the Willie Bird processing plant and Benedetti Farms. He also sold the Willie Bird brand to the Diestel Family Ranch, another fourth-generation family farm and friends of the Benedettis who promise to keep Willie’s legacy alive. ♦

The setup

Nathaniel Hamilton

Managing Editor

Jim Burling

Vice President of Legal Affairs

IN 1902, WILLIAM WARLEY was getting ready to graduate from Central High School in Louisville, Kentucky. Warley, as one of the top students at Central and a leader of his class, was a bright, charismatic young Black man looking to make his mark on a country that didn’t yet value your intellect—or your rights—if you were the wrong color.

As Warley prepared himself to walk across his high school stage and accept his diploma, he was planning one of his first acts of civil disobedience. While he was on stage accepting his diploma, in front of the entire student body, parents, and, most importantly, teachers and administrators, the teenaged Warley planned on giving an impassioned speech about the pitiful state of Central High.

Thanks to the pernicious “separate but equal” rule endorsed by the Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson, Central was the only Louisville high school that Black students were allowed to attend—and the education it provided was dismal. The school didn’t even offer a four-year program until 1893, and now in 1902, if any Central graduates wanted to go on to college, most had to take two years of college prep courses just to be adequately prepared.

Warley was going to expound on all of this and admonish the school’s leaders for failing the students they were entrusted to prepare for the world. Even as a teen, Warley was a passionate advocate for individual rights, and his speech promised to be something Central students and administrators would never forget.

But rumors about his planned speech got around and one of his favorite teachers, Mr. Mclellan (who would go on to write for the newspaper Warley started after he graduated college), spoke to the young firebrand and convinced him that, while his frustrations were valid, it wasn’t enough just to be right, he needed to think about the most effective way to achieve change.

Teacher got through to student and Mr. Mclellan convinced Warley that chastising the school during graduation wasn’t the best way to induce change. But Mclellan’s advice did more than help the young Warley avoid potential backlash—it also served as an important final lesson for the soon-to-be-graduate: fighting for what’s right requires passion and bravery, but winning victories for what’s right requires intelligence, creativity, and strategy.

Warley would take that lesson to heart. And it’s that lesson that would take him all the way to the Supreme Court as part of one of the most important civil rights and property rights cases of all time.

TO UNDERSTAND WARLEY, you need to understand the era and the town he grew up in.

William Warley was a Louisvillian from the day he entered into this world. He was born in the city on the river on January 6, 1884, to a South Carolina father and a Louisiana mother. Both his parents were Black southerners who had come “up north” to Louisville in the late 1800s. Louisville was an attractive city for Black Americans after the Civil War. Former Rhodes College history professor and administrator Russell Wigginton explains, “The two most prominent reasons that Blacks were drawn to Louisville were that the virulent forms of racism present elsewhere in the South were absent, and most Blacks in the city could find respectable nonagricultural work.”

But despite its general respect for equality before the law, turn-of-the-century Louisville wasn’t a city of perfect racial harmony. When describing Louisville, a Black reporter of the time wrote, “[the] races get along nicely—like oil and water—the whites at the top and the Negroes at the bottom.”

Warley grew up an only child sequestered to the subpar Black schools in Louisville, but he refused to be a victim of his position. He excelled in school, and after he graduated high school (sans firebranding speech), he attended State University in Louisville.

During his college years and after he graduated, Warley bounced around a couple of jobs. At first, he got a job as a doorman for a Louisville social club (the all-white Pendennis Club) and then became a mailman for the post office. But while being a postman was a high-status position for a Black man in Louisville at the time, Warley was unsatisfied with simply having a job that others were impressed with. So he teamed up with a successful Black businessman in Louisville, Lee Brown, and created the Louisville News newspaper.

The Louisville News was, as Warley described it, a “race paper” with “reading[s] of particular interest to colored people.” Now, with his own newspaper, William Warley had the platform to fight for the individual rights of Black Louisvillians. For example, in 1914, Warley used the Louisville News to lead a boycott of a theater in Louisville that discriminated against Black theatergoers by forcing them to use the back entrance of the theater and allowing them to occupy only the top balcony seats. The boycott was successful in forcing the theater to rescind the racist policies, and it also helped establish Warley as a leader of the civil rights movement in Louisville.

And the civil rights movement in Louisville was about to be tested more than it ever had been before.

Louisville in 1910

IN THE 1910s, there was newfound opportunity away from the farm, and more Americans were moving to cities to experience it for themselves. Louisville was one of those cities on the rise.

Louisville’s population at the turn of the 20th century exploded. According to U.S. Census data, the city’s population in 1880 was 123,758. In 1910, it was nearly 224,000, and 18% of that population was Black.

As Louisville’s Black population grew, some of the city’s white residents grew uneasy that more and more Black families were moving into middle-class and upper-class neighborhoods. One of those “concerned citizens” was Walter Binford. Binford, who was white, was the superintendent of the mechanical department of the Louisville Courier-Journal newspaper and led a campaign encouraging the city council to pass a segregated zoning law. According to The Journal of Southern History (Vol. 34, No. 2), Binford gave a speech in 1913 to a local real estate group expounding on the horrors white Louisville families were being put through by living next to Black families: “One morning they awoke to find that a Negro family had purchased and was snugly ensconced in a three-story residence in one of the best and most exclusive white squares in the city.”

Binford’s despicable race-baiting and scare tactics didn’t work on the city’s real estate businessmen, many—if not most—of whom were vehemently against any segregated zoning law being passed in Louisville. But it did garner the attention of Democrats on the city council (then called the “Board of Aldermen”), and in 1914 the city passed one of the country’s first segregated zoning laws.

The title of Louisville’s new law said it all:

An ordinance to prevent conflict and ill-feeling between the white and colored races in the city of Louisville, and to preserve the public peace and promote the general welfare, by making reasonable provisions requiring, as far as practicable, the use of separate blocks, for residences, places of abode, and places of assembly by white and colored people respectively.

It had the supposedly separate but equal provisions: Just as no Black person could buy property and move into a predominantly white neighborhood, so too could no white person buy property and move into a mostly Black neighborhood. But the equality was a sham, the Board of Aldermen weren’t concerned with keeping white families out of rich Black neighborhoods, the law served to keep Black Louisvillians stuck in poorer and more run-down neighborhoods.

Just three months after the ordinance was adopted, the city prosecuted its first case. In August, Arthur Harris (who was Black) moved into a house in a white block. He was summoned to appear before a police court and found guilty of violating the new law. In December, the court upheld the conviction, stating that the ordinance “was extremely mild in its operation,” that it had a “scrupulous regard for property,” and that while the ownership of property was important, it could be regulated by the government–as settled by the Supreme Court in the Plessy v. Ferguson “separate but equal” railroad car case. This would be the first criminal conviction based on the law. But it was Mr. Warley’s subsequent civil suit that would put it to the most serious test.

IN THE LEAD-UP to Louisville passing the segregated zoning ordinance, Warley and the other Black leaders of the city knew they would have to be organized to have any chance of defeating the racist law, so they formed a local NAACP chapter and Warley was named president.

After seeing the futility of the political process, Warley and the NAACP turned their attention to the courts and began orchestrating a strategy that would (hopefully) induce the Supreme Court to overturn Louisville’s ordinance and segregated zoning ordinances like it in other cities across the country.

But first, they needed a case.

While Warley was campaigning against the ordinance before it passed, he found himself teaming up with white members of Louisville’s business community. Many local business leaders didn’t want anything to do with Jim Crow-style laws seeping into Louisville. Aside from the obvious moral reasons to oppose legally required discrimination, it was also bad for business. Having to create separate spaces and allocations for Black patrons and white patrons is expensive, and for businessmen in the real estate market, being allowed to sell/buy land and houses to/from only one race limits opportunities and slashes profit margins.

One of those business leaders Warley teamed up with was Charles Buchanan, a white real estate developer and realtor who wanted Louisville to stay free from any Jim Crow laws—especially any Jim Crow-styled zoning laws that threatened to decimate his real estate business. After the ordinance passed, Warley and Buchanan teamed up again to develop one of the most innovative Supreme Court cases ever argued in front of the nation’s High Court.

IN TERMS OF litigation creativity, Warley and Buchanan’s plan was brilliant.

They found a residential block of Louisville that had 10 homes—eight white families and two Black. Then Buchanan bought an undeveloped lot on that block which he turned around and agreed to sell to Warley. But in the contract for the sale, Warley and Buchanan put in an unusual—and very specific—provision:

It is understood that I [Warley] am purchasing the above property for the purpose of having erected thereon a house which I propose to make my residence, and it is a distinct part of this agreement that I shall not be required to accept a deed to the above property or to pay for said property unless I have the right under the laws of the State of Kentucky and the City of Louisville to occupy said property as a residence.

Both men signed the contract, but then Warley attempted to back out of the sale, citing Louisville’s segregated zoning law as the reason. After Warley tried backing out, Buchanan sued Warley for breach of contract, arguing that Louisville’s zoning law was unconstitutionally preventing him from selling his land to whomever he chose.

Buchanan lost the case at the district and appellate court levels, which meant the next step was the U.S. Supreme Court.

If this were a heist movie, here’s the part where everything lines up before the big score.

The Supreme Court hearing Buchanan v. Warley was the same Court that established the “separate but equal” doctrine, so Warley and Buchanan knew that making arguments against segregation would be losing battles. But Warley and Buchanan had concocted a perfect setup that challenged Louisville’s law on property rights and economic liberty grounds instead of the equal protection and discrimination grounds they knew the prejudiced Supreme Court would reject. Their case presented a Black man arguing that Louisville’s segregated zoning law shielded him from his contractual obligation while a white man was arguing that the law was unconstitutional. And to add to the irony, Buchanan was represented by the NAACP (which Warley was still president of) and Warley was represented by the Louisville city attorney.

The NAACP’s (Buchanan’s) arguments were careful not to expound about how Louisville’s law violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause (even though it did). Instead, Buchanan’s NAACP attorneys focused their arguments on how Louisville’s law violated Buchanan’s property rights and contract rights by preventing him from selling his land to a Black man wanting to live on it.

The arguments worked.

On November 5, 1917, the Supreme Court issued its opinion. First, the Court emphasized the importance of property rights in American law:

The Fourteenth Amendment protects life, liberty, and property from invasion by the states without due process of law. Property is more than the mere thing which a person owns. It is elementary that it includes the right to acquire, use, and dispose of it. The Constitution protects these essential attributes of property…. Property consists of the free use, enjoyment, and disposal of a person’s acquisitions without control or diminutions save by the law of the land.

Headlines in newspapers across the country covered the Buchanan v. Warley decision.

Property rights were the key to defeating the law.

Even though the Court had wrongly decided previous segregation and discrimination cases, Warley v. Buchanan forced it to recognize and uphold the true intent of the Fourteenth Amendment: secure property rights and economic freedom for people regardless of someone’s race. As the decision states:

Colored persons are citizens of the United States and have the right to purchase property and enjoy and use the same without laws discriminating against them solely on the account of race.

Warley and Buchanan’s plan came to fruition perfectly; Warley “lost” the case but won the fight.

WILLIAM WARLEY WOULD stay active in Louisville politics and the civil rights movement for the rest of his life after Buchanan v. Warley. His victory in that case, however, would prove to be his most lasting.

Even though the Supreme Court would later on uphold zoning schemes that segregated people by income—which often had a similar effect as segregation by race—the legacy of Buchanan v. Warley cannot be overstated.

First, it pioneered the use of carefully constructed cause-oriented litigation to achieve a just result.

Second, it demonstrated the powerful connection between private property rights and the rest of our constitutionally protected rights. While the Supreme Court at the time was unwilling to strike down Jim Crow laws, it was willing to halt segregation when it had obvious and negative impacts on private property rights.

And lastly, it gave rise to a new legal specialty—public interest litigation where groups like the NAACP, the ACLU, and later Pacific Legal Foundation were able to vindicate constitutional rights for all Americans.

Warley might not have known the lasting impact his case would have for the nation, but he understood that the fight for civil rights, at its core, is a fight for property rights.

The Supreme Court’s prejudice in the early 1900s forced the parties of Buchanan v. Warley to battle Louisville’s segregated law using property rights arguments, but property rights’ importance in the fight for freedom and equality is why they were ultimately successful.

William Warley’s fire for fighting injustice burned hot his entire life. But he never forgot Mr. Mclellan’s lesson: Passionately fighting for your rights is always the right thing to do, but fighting intelligently—and achieving results—is the most important. ♦

Poison pill

Jaclyn Boudreau

Creative Director

Jim Burling

Vice President of Legal Affairs

PEYMAN PAKDEL AND HIS WIFE, SIMA are the kind of neighbors most people want.

Peyman is an engineer who worked his way up to become part-owner of a small manufacturing company, Sima is a dentist with a family practice. Peyman and Sima are both immigrants. They raised their three children in Northwest Ohio.

In 2009, the Pakdels used their savings to buy a unit in a small condo building in San Francisco. They had friends in the Bay Area and planned eventually to retire there. In the meantime, they rented their unit to a young tenant.

They were living the American dream—years of hard work bringing them close to the future they imagined for themselves.

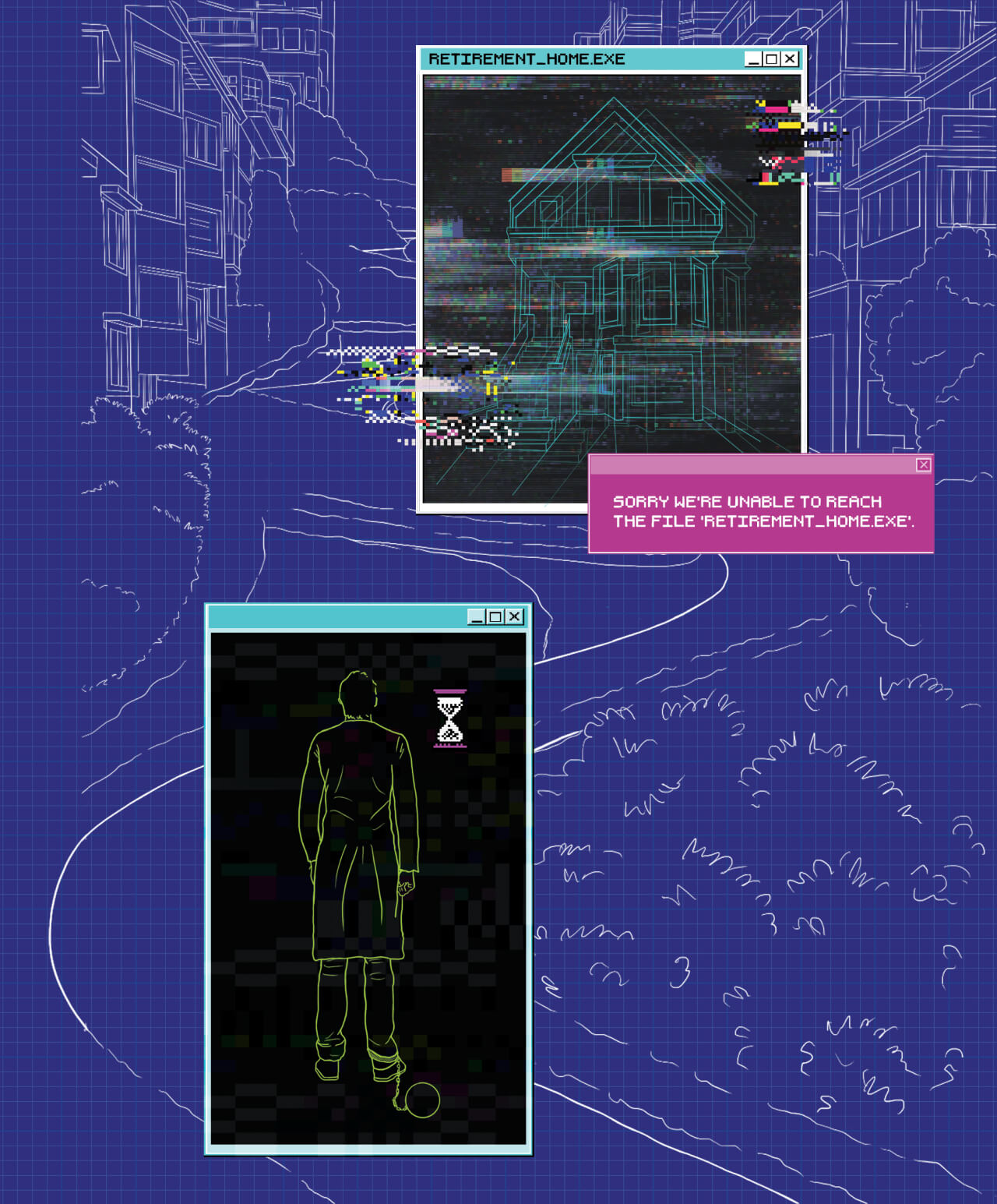

But when San Francisco changed the permitting laws for condos like the Pakdels’, which forced them to offer a lifetime lease to their tenant, their retirement dreams were thrown into turmoil.

The retirement home the Pakdels planned for would no longer be possible—unless they took the City of San Francisco to court.

A home in Russian Hill

PEYMAN HAS BEEN working 12-hour days for the past 20 years. He usually gets to work at 5 a.m. and doesn’t get much down time during the day, “It’s been my life with very little vacation or time off,” Peyman says. He and Sima want to retire to San Francisco while they’re still lucky enough to be healthy. “We’re getting pretty close to the end of our road in terms of physical ability and being able to enjoy life,” he says.

San Francisco’s Russian Hill neighborhood is known for its beauty. Jack Kerouac used to live there; so did Governor Gavin Newsom. It is home to the San Francisco Art Institute and was the setting for Steve McQueen’s car chase scene in Bullitt. For Peyman and Sima, Russian Hill seemed like an ideal place for a retirement home.

The unit they purchased in 2009 was one of six carved out of a 1913 home in Russian Hill. It was a Tenancy in Common building: Unlike in a standard condo building, where each owner owns a specific unit, tenants in common each own a share of the whole building.

But the Pakdels and the other owners were interested in converting to a traditional condo building at the earliest opportunity. As part of their purchase agreement, the Pakdels had to agree to cooperate with the co-owners’ efforts to convert. At the time, converting a Tenancy in Common building to a condo building was a relatively simple process in San Francisco, though the permitting process could take a long time. Two hundred applications were granted every year under a city lottery system.

The Pakdels and the other owners worked with the city to begin the conversion process, but not yet ready to retire, and still living in Ohio, they rented their unit to a tenant. Something they never would have imagined would lead to years’ worth of turmoil.

Forced to offer a lifetime lease

IN 2013, the City of San Francisco passed a new ordinance that converted the city’s lottery process for condo conversions to a new process that required each unit owner to pay $20,000. Also—incredibly—any owners who were renting their unit to a tenant would have to offer their tenant a lifetime lease.

Why would the city force homeowners to allow tenants to remain in their units permanently? The city claimed the bizarre new requirement was necessary to prevent a mass displacement of tenants as buildings converted to condos. But the move may actually have been something of a salvo in the ongoing cold war between renters and property owners in the city. San Francisco has some of the strongest tenant protections in the country and anti-landlord sentiments are common. (“I can’t take being an SF landlord any longer,” one landlord blogged anonymously in 2014. “I’ve suddenly become a bad word in this town.”)

To Peyman, the new lifetime lease requirement was completely absurd. “I understand the concern about evictions,” he says. But he and his wife had never evicted anyone. They had only one property in San Francisco and had always intended to eventually move into it.

“It’s just hard to believe that such an ordinance can be written by really intelligent people,” he says. “It really shocks the conscience when you read through this document.”

As justification for the new rules, the city cited a report it had commissioned on the economic impact of condo conversions. Peyman tracked down the report, which wasn’t easy to find.

“This report is really a piece of art,” Peyman says. “You have to be completely insane by any measure to define this report a plausible scientific report that a city should rely on. It’s completely cooked up to justify the $20,000 fee for conversion.” The report didn’t include any analysis of the economic impact of mandatory lifetime leases, which, Peyman points out, would certainly decrease property values.

“When you have somebody else living in your apartment for their entire life, what is the word for that agreement really?” Peyman asks.

Perhaps aware that the lifetime lease requirement was unconstitutional, the city included a so-called “poison pill” in the ordinance intended to prevent legal challenges. If any owner sued to challenge the lifetime lease, the city would immediately halt all condo conversions for buildings with even a single tenant. San Francisco even sent a notice to all the landlords potentially affected by the new policy that included the Pakdels’ name and address.

The Pakdels were outraged. Their purchase agreement required them to cooperate with condo conversion efforts. Now, because of San Francisco’s ordinance, cooperating meant agreeing to pay the city thousands of dollars, offering a lifetime lease to their tenant, and accepting the city’s trumped-up justifications.

“When I was studying this, my blood was boiling,” Peyman says. “Because how in the world in the United States can such a thing happen?”

There was no way out of it. When their building began the process of converting to condos in 2015, the Pakdels were forced to offer their tenant a lifetime lease.

Fighting back

“IT WAS VERY DEVASTATING,” Peyman says. “And there were many nights that I couldn’t sleep.”

The Pakdels asked the city to either excuse them from the lifetime lease or compensate them fairly. The city refused.

“Nobody goes against the City of San Francisco,” Peyman says.

He asked other property owners in San Francisco for advice. “They said, basically, this city is going to fight tooth and nail on anything,” he says. “So you’re never going to succeed on a land case against the City of San Francisco. But I felt so violated that I had to do something.”

In 2017, despite the poison pill in the ordinance, the Pakdels filed a lawsuit against the City of San Francisco in federal district court. They argued the city had violated their Fifth Amendment rights. By forcing the Pakdels to allow their tenant to remain in the property permanently, the city had effectively taken their property without just compensation. The Pakdels’ complaint relied on precedents set by two Pacific Legal Foundation victories: Nollan v. California Coastal Commission (1987) and Koontz v. St. Johns Water Management District (2013).

But the district court dismissed the Pakdels’ case on the grounds that it wasn’t “ripe” for review because the Pakdels hadn’t exhausted the city’s administrative processes or filed in state court first.

That’s when PLF joined the Pakdels’ case. Working alongside the Pakdels’ private attorneys, PLF brought an appeal to the Ninth Circuit Court. Unfortunately, in a March 2020 decision, the Ninth Circuit agreed with the district court.

But meanwhile, PLF had won a significant U.S. Supreme Court victory in a different case: Knick v. Township of Scott (2019). In the Knick opinion, the Court held that property owners can bring takings claims to federal court without first having to exhaust state remedies “because the violation is complete at the time of the taking.”

Bolstered by this new precedent in Knick, PLF brought the Pakdels’ case to the Supreme Court. In its June 28, 2021, decision, and PLF’s 14th Supreme Court victory, the Court reversed the lower courts’ rulings and, citing Knick, held that the Pakdels had a right to bring their takings claim against San Francisco to federal court.

“In this case,” the Court wrote in its 9-0 decision, “there is no question about the city’s position: Petitioners must ‘execute the lifetime lease’ or face an ‘enforcement action.’ And there is no question that the government’s ‘definitive position on the issue [has] inflict[ed] an actual, concrete injury’ of requiring petitioners to choose between surrendering possession of their property or facing the wrath of the government.”

Now the courts must consider the Pakdels’ argument that San Francisco violated their Fifth Amendment rights when it forced them to lease their property to their tenant for life.

“The Pakdels will finally have their day in court, as they deserve,” notes PLF attorney Jeffrey McCoy.

A violation of basic rights

IT’S BEEN EIGHT years since San Francisco passed the ordinance that destroyed the Pakdels’ plans for their Russian Hill retirement home.

Their case is far from over. “There’s a long way ahead of us,” Peyman says. But the peaceful retirement they imagined in picturesque Russian Hill may be a lost cause.

“Even, at this point, if we do not reach our conclusion—which is being able to live in that place—I’m very grateful for PLF,” Peyman says. He believes the case will help other people. “We can show to ordinary citizens of this city that you really need to stand up for your rights,” he says.

And he believes that the courts will finally see how unfairly San Francisco treated the Pakdels.

“If we could show to the court what the city has done in the process of coming up with this ordinance, I do not think there’s any reasonable minds in the United States that can side with the city,” Peyman says.

After all these years, Peyman still seems genuinely puzzled by San Francisco’s actions. How could one of America’s most popular cities force property owners to lease their home permanently against their will?

“It’s a violation of basic rights in housing,” Peyman says.

He points out that San Francisco is a city that prides itself on liberal ideas. If you believe in liberty and the pursuit of happiness when it comes to social issues, he argues, you should know those same rights also encompass the home. ♦

Cari and Bob Koch secured a lasting legacy for family and PLF by establishing a Charitable Remainder Trust, or CRT.

“It was absolutely a perfect solution for us… the beauty of donating through a CRT was threefold: I received a tax benefit for making the donation; I was able to contribute it right into the trust and receive an income stream of 5% of the donated value, and I was able to support a nonprofit that I really believe in.”

Is a Charitable Remainder Trust right for you?

- Do you have a large portion of your portfolio invested in one or more stocks that have significantly appreciated in value?

- Do you own property that you are considering selling?

- Do you want to receive an income for life?

- Are you interested in making a significant impact on PLF’s future?

A CRT allows you to sell either appreciated stock or property without paying capital gains. It also pays you or your family a lifetime income and provides for PLF in the long term.

Become a Legacy Partner Today

Contact Jim Katzinski, Gift Planning Officer, at (916) 288-1395 or jkatzinski@pacificlegal.org for more information on Charitable Remainder Trusts or other ways to include PLF in your estate plans.