Winter 2022

The Water Issue

To read more about the work that PLF is doing, visit pacificlegal.org.

Much has happened to me in the past 15 years. I accepted a series of work roles with increasing responsibility in one organization, which prepared me for the job I have now with Pacific Legal Foundation. I’ve moved cities and ultimately coasts, from Washington, DC, to California. I got engaged, then married. My wife and I have brought two humans into the world, who are now deep in elementary school. I was even able to see my alma mater—in person, no less—win the NCAA championship in basketball, something I’d never imagined would occur in my lifetime. It’s been memory after memory.

For Chantell and Mike Sackett? Nothing. Bupkis. Nada. Zilch. At least when it comes to their plan of building a modest three-bedroom home near Priest Lake, Idaho. For the past decade and a half, their lot has sat empty, all construction halted because the Environmental Protection Agency alleges it’s a wetland protected by the Clean Water Act. Had the Sacketts continued to build, they’d be subject to thousands of dollars in fines. Per day. Considering the Sacketts have been stuck in regulatory limbo for more than 5,000 days, the costs are potentially life-ruining.

Actually, it would be unfair for me to express that nothing has happened for the Sacketts over that time. Their legal issues have been argued not once, but twice before the U.S. Supreme Court. They join a very rare club—although one to which no rational person wants to belong—of repeat Supreme Court litigants. All of this to build a home in an already developed subdivision in remote Northern Idaho.

This is just one family. But what’s happening to the Sacketts happens to countless families and businesses across the country every day, every year. It’s the result of an administrative agency run amok—utilizing vague definitions in congressional statutes to accumulate and aggrandize their power. For all the good the EPA may arguably do, no one goes to work there to fast-track residential developments, office parks, or factories. It’s classic public choice theory—civil servants don’t magically become angels when working for the government. They’re humans who respond to incentives, and the incentives here are to restrict human activity and keep resource utilization to its barest minimum. Multiply that attitude by the seemingly innumerable array of federal, state, and local bureaucracies, and you’re left with a world in stasis.

At Pacific Legal Foundation, however, we value human enterprise and the heightened standard of living brought by mixing ingenuity, entrepreneurship, gumption, and, yes, assets from our external environment. It lifts us from poverty while also lifting our spirits. Simply put, it’s the fount of human flourishing.

We’re optimistic the Sacketts will win—again—at the Supreme Court and finally finish what they started. We do this work because we understand the trajectory of their lives—no, the trajectories of everyone’s lives—are permanently affected when caught like this in the government’s web. And we’re left to wonder exactly how different the Sacketts’ memories would be, had they simply been left alone.

Steven D. Anderson

PRESIDENT & CEO

How the Sacketts Got Stuck in a Kafkaesque Nightmare

James Burling

Vice President of Legal Affairs

“Somebody must have slandered Josef K.,” Franz Kafka writes in the opening line of The Trial, “for one morning, without having done anything wrong, he was arrested.” Josef K. spends the novel in a futile (and ultimately fatal) quest to learn from a mindless bureaucracy what his supposed crime is and how he can prove his innocence.

At one point, a priest tells Josef K., “It is not necessary to accept everything as true. One must only accept it as necessary.”

The Environmental Protection Agency has adopted this same stance in the case of Sackett v. EPA, which has now spanned 15 years and gone to the Supreme Court twice, most recently in October.

For the EPA, it’s not necessary to accept as true that Mike and Chantell Sackett were endangering waterways when they tried to build a home on their landlocked residential lot. The Sacketts are just supposed to accept that it’s necessary for their property to remain empty.

If the agency had its way, the Sacketts would have surrendered back in 2007—and accepted whatever fate the EPA dealt them.

“[I]t means they’re dealing with a serious criminal if they send an investigating committee straight out to get him.”

— The Trial, Franz Kafka

On May 3, 2007, three EPA officials showed up unannounced on the Sacketts’ residential lot in Priest Lake, Idaho.

Mike and Chantell Sackett weren’t there; but a small construction crew was working on their two-thirds-acre lot, which is a stone’s throw from other houses. The Sacketts planned to build a modest three-bedroom home there. The construction crew was moving gravel in preparation.

Until the government arrived.

The Sacketts’ contractors were ordered to stop work. The lot, the EPA announced, contained some wetlands. Spreading clean gravel was “filling” the alleged wetland, which the Clean Water Act prohibits without a permit.

One of the Sacketts’ workers asked the EPA what authority it had to shut down a job site. When asked for evidence the property contained wetlands, one EPA official vaguely said there was water on the property. (It was later revealed that the officials had received an anonymous “tip” about the property and had come from as far as Boise—an eight-and-a-half-hour drive away—to check it out.)

The next day Chantell spoke to an EPA official on the phone. When she protested that there were no wetlands on the lot, the official told her they were on the EPA’s wetland map. But after Chantell reviewed the map, she called the EPA and told them that her property was not on the map.

The EPA’s response? “Well, those maps aren’t accurate.”

“Look at this, Willem, he admits he doesn’t know the law and at the same time insists he’s innocent.”

— The Trial, Franz Kafka

In June, the Sacketts received a formal-looking “Request for Information” from the EPA. Sent by certified mail, the 10-page document announced the EPA was “investigating” the Sacketts and issued a list of questions. Mike and Chantell were given 15 days to respond and told that “failure to provide all the information requested” may constitute a violation of the Clean Water Act, punishable by “an enforcement action and the imposition of civil and/or criminal penalties or fines.”

The questions the EPA demanded answers to were somewhat daunting, especially given that Mike and Chantell didn’t believe their property contained wetlands. For example:

10. Provide a list of name(s), address(es), and telephone number(s) of any person(s) involved with the discharge of dredged and/or fill material at the Site into waters of the United States, including wetlands. For all individuals named, identify his/her employer and the manager, if any, who instructed him/her to perform the work.

Were Mike and Chantell supposed to give the personal information of the construction crew members who’d been working on the property? Wouldn’t answering the question be seen as tacit admission that the crew had been filling a wetland, which the Sacketts did not believe was true?

In their response to the EPA, Mike and Chantell stressed that they had local building permits in hand. They also pointed out that their lot was surrounded by paved roads and developed properties. It wasn’t like they were trying to build in the middle of the wilderness.

Instead of backing down, the EPA ordered Mike and Chantell to remove the gravel, restore the alleged wetlands, plant wetlands vegetation, fence off the property, and then wait a few years. Only after a few years could they apply for a permit—a permit which, by the way, takes on average 788 days and $271,596 to obtain.

This wasn’t just a request. It was an order. And the EPA made clear that if the Sacketts didn’t comply, they would be saddled with fines of thousands of dollars per day for violating the order.

What’s even worse is that if the Sacketts had done exactly as the compliance order said, they still wouldn’t have been able to build their home. An EPA official eventually told an upset Chantell that she would likely never get a permit for the lot and should consider building elsewhere.

“Judgment does not come suddenly; the proceedings gradually merge into the judgment.”

— The Trial, Franz Kafka

Naturally, the Sacketts wanted to contest the EPA’s finding that their lot contained wetlands. But the EPA said no. In a mash-up of Kafka and Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, the EPA told the Sacketts they couldn’t challenge any wetlands determination until after they applied for (and were denied) a wetland “dredge and fill” permit.

In other words: Once the EPA says your land contains wetlands, you have no choice but to apply for a permit to fill wetlands—even if you’re certain the land doesn’t actually contain wetlands.

It’s not necessary to accept everything as true. One must simply accept it as necessary.

After the Sacketts sued, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with the EPA. Fortunately for Mike and Chantell, the U.S. Supreme Court heard their case and ruled unanimously that they had a right to challenge the wetlands finding without having to follow the EPA’s dog-and-pony-show permit process.

That was in 2012. You’d think that after winning the right to make their case, things would move quickly for the Sacketts.

But the EPA, an $11-billion agency represented by a team of lawyers at the Department of Justice, can make the wheels of justice turn slowly.

After the first Supreme Court victory, the Sacketts’ case went down to the trial court. The EPA spent the next several years collecting samples and gathering evidence that they presented to the court as proof that the property had wetlands.

But the EPA’s “proof” was problematic.

In order to regulate anything, a federal agency has to meet two tests. First, the U.S. government can act only according to a power spelled out in the Constitution. And second, Congress must give the regulating agency the power to regulate. Here, the constitutional power is found in the Commerce Clause, which gives the federal government the exclusive power to regulate commerce among the states. And the statutory power is found in Section 404 of the Clean Water Act.

Exactly how does building a three-bedroom home in an Idaho subdivision involve commerce among the states? And where does the EPA or the Army Corps of Engineers find authority in the Clean Water Act, which never actually defines what a wetland is?

The EPA’s theory is that because the Sacketts’ lot is 300 feet from Priest Lake, which is large enough for recreational boating, building a home on the Sacketts’ lot would affect interstate commerce.

Never mind that the property is in a residential subdivision, separated from the lake by a road and a block of homes, and has no meaningful hydrological connection to Priest Lake. In the EPA’s view, that’s close enough—at least, close enough for government work.

“And what, gentlemen, is the purpose of this enormous organization? Its purpose is to arrest innocent people and wage pointless prosecutions against them which, as in my case, lead to no result.”

— The Trial, Franz Kafka

If the EPA has its way, millions of American homeowners could wake up one morning and find themselves in the exact same position as the Sacketts: at the wrong end of a Clean Water Act investigation, with little hope of proving your innocence.

After all, it’s impossible to follow federal wetlands rules when no one knows exactly what a wetland is.

In one notorious case, the Army Corps of Engineers claimed to have jurisdiction over quarry ponds in Illinois that had absolutely no connection to any navigable waterway. Instead, the Corps adopted what became known as the “glancing goose” test: Because ducks and geese might land on the ponds, and because people might cross state lines to hunt migrating birds, there was enough of a connection to interstate commerce to regulate the ponds.

After all, it’s impossible to follow federal wetlands rules when no one knows exactly what a wetland is.

In that 2001 case, Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. United States Army Corps of Engineers, the Supreme Court didn’t buy it. It held that the ponds were free of federal control. But that didn’t stop the federal government from trying other novel approaches to expand its jurisdiction.

In 1989, developer John Rapanos was preparing a 54-acre parcel of farmland that was at least 11 miles from a navigable waterway. Regulators swooped in, telling him he needed a permit because the land was a wetland and thus “water of the United States” covered by the Clean Water Act.

Twelve years of threats and litigation followed.

PLF took John’s case to the Supreme Court, arguing that the land was not a wetland subject to federal jurisdiction. In 2006, the Court agreed, but only partially: It began by noting that “the enforcement proceedings against Mr. Rapanos are a small part of the immense expansion of federal regulation of land use that has occurred under the Clean Water Act—without any change in the governing statute.”

While five Justices agreed that the regulators had gone too far, they couldn’t agree why. Led by Justice Antonin Scalia, four Justices said that there had to be a surface water connection to a navigable waterway for the feds to control a wetland. Without that, the feds had no power over John Rapanos.

Four other dissenting Justices said, essentially, “Whatever EPA says is good enough for us.” And Justice Anthony Kennedy issued a lone opinion, saying that for the government to be able to regulate a wetland, the regulators must show that activity on the alleged wetland will “significantly affect the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of other covered waters more readily understood as ‘navigable.’”

The problem is that no one has ever figured out exactly what that means.

Lacking a five-vote majority, the EPA and most lower courts have defaulted to Justice Kennedy’s so-called “significant nexus” test—which in practice involves so many complicated factual studies that the courts usually just throw up their hands and go along with whatever the Army Corps or EPA says.

“[T]hat’s how this court does things, not only to try people who are innocent but even to try them without letting them know what’s going on.”

— The Trial, Franz Kafka

The EPA wanted the Sacketts to apply for a Clean Water Act permit. But who can afford that?

Sources: Federal Reserve report, USDA, Harvard website, Rapanos v. United States

On October 3, 2022, PLF senior attorney Damien Schiff argued the Sacketts’ case at the Supreme Court a second time—a decade after he first took the case to the Court. This time he challenged the EPA’s determination that Mike and Chantell’s property contains federally protected wetlands.

The Court’s decision, which will likely come in the spring, will finally give the Sacketts an answer to the question they’ve been pursuing for 15 years: Did the federal government have the right to stop construction on their home? It should also clarify the split Rapanos decision from 2006 and give us a long-overdue common sense understanding of what a wetland subject to federal jurisdiction looks like.

When a wrong guess could cost millions of dollars in fines and jail time, it shouldn’t be this difficult for the average person to know whether a piece of ground is subject to federal oversight. And the federal government shouldn’t act like the de facto land-use czar in every state and county in the nation.

In Kafka’s The Trial, Josef K. spends the remainder of his short life wandering from government office to government office trying desperately to prove his innocence of an unknown crime. In America today, landowners must spend their time and money seeking permits to work on property that may or may not contain wetlands that may or may not be subject to federal oversight.

Unless the Supreme Court clarifies the matter, if a citizen guesses wrong, he may join Josef K. in the annals of people ground under the wheels of the bureaucratic state. And that’s precisely what PLF exists to prevent. ◆

Earth, Wind, and Water: 1970s Activists and the Administrative State

Frank Garrison

Attorney

In the late 1970s, two sociologists asked: Where had all the 1960s radical activists—the countercultural voices who clamored for a revolution—ended up in the seventies?

The answer, published in a 1980 study, was somewhat startling: Many former radicals were now working in or with the government. They were no longer fighting “the Man.” Instead, the Woodstock Generation had gone to Washington to join the man—fighting to give the government unprecedented power over Americans’ lives.

Indeed, from within and alongside the government, progressive activists spent the 1970s helping to grow the administrative state—mostly in the name of protecting the environment at the expense of individual liberty.

One of the Chicago 7 became deputy director at a federal agency. Another former activist turned government employee told the sociologists, “Everyone’s been co-opted but that’s the genius of the system. It’s not a mark of failure, but of success.”

Indeed, from within and alongside the government, progressive activists spent the 1970s helping to grow the administrative state—mostly in the name of protecting the environment at the expense of individual liberty. The anti-authoritarian “flower power” of the late sixties was morphing into a flower power of a different kind: regulatory power wielded like a weapon to protect nature from human beings at any cost.

‘Big Brother Is Watching You’

When countercultural activists came to Washington to push various social causes, they quickly clashed with an older class of government workers.

“Nader’s Raiders” exemplified the new activist mindset. Harvard Law graduate Ralph Nader recruited students from across the country to pressure the federal government into regulatory action on automobile safety, trade, and the environment.

“Our children are children of smog, who have never known fresh water, or clean air,” Nader opined.

Nader and his Raiders took early aim at the Federal Trade Commission in a blistering 1969 report that said current FTC staffers displayed “a lack of commitment to the regulatory mission.”

But as syndicated columnist John Chamberlain quickly pointed out, the report unveiled a fault-line disagreement about how the federal government should behave.

“There is a gap as wide as the Atlantic Ocean between [then-FTC Chairman Paul Rand] Dixon’s philosophy of what a regulatory agency should do and the philosophy expressed by the Nader-organized investigative team,” Chamberlain wrote.

Dixon, who grew up during “the hard knocks period of the depressed thirties,” firmly believed the government should not enforce a law “that the people don’t want enforced,” Chamberlain noted.

But Nader’s Raiders, who came of age during the affluent sixties, considered this “a horrifying softness.”

“Their report makes it obvious that they want a Federal Trade Commission that would multiply its staff and budget many times over, engaging in positive detective work… In short, a ‘Big Brother Is Watching You’ approach,” Chamberlain wrote.

Dixon called the Nader youths “young zealots,” and Chamberlain complained that “the gimlet-eyed gumshoeing advocated by the students for policing detergent and mouthwash sales” would “cost billions.”

Despite these well-founded concerns, the students’ philosophy soon became the norm in Washington.

The New Generation of Big Government

Throughout the seventies, new federal hires took up the mantle of “positive detective work.”

The makeup of federal agencies thus shifted. Rutgers University professor Jefferson Decker describes the shift at the Bureau of Land Management: Up until 1970, BLM hired mostly range-management experts from public universities in western states, where most federal land management occurs. “In the 1970s, however, a new sort of Interior Department bureaucrat began to appear on the job,” Decker writes. The new staffers weren’t from western states, and their interest wasn’t in range management; it was in ecology.

Put differently, they were in public service to further a cause, not to engage in reasoned decision-making and implement the policies as directed in their statutory mandates.

But not all activists who flooded Washington ended up working for the government. Progressive public interest groups were “sprouting like daisies,” as the Los Angeles Times reported in the early seventies. Alongside Nader’s Raiders were hundreds of other advocacy groups that began pulling the government in different directions, sometimes through lawsuits that forced agencies to aggressively enforce rules already on the books.

But older laws and regulations did not go far enough for the activists’ progressive vision. And ultimately Congress cooperated by delegating vast power to administrative agencies through new laws that built a regulatory architecture for the fresh, more aggressive generation of pro-government regulators.

Bills like the Egg Products Inspection Act, Noise Control Act, and Federal Boat Safety Act churned out of Washington at a dizzying pace—and quickly altered Americans’ personal experience with federal regulations. Until the seventies, complex federal rules had been reserved for industries: Most people were only affected by regulations when on the job, if at all. Now, Jefferson Decker writes in his book The Other Rights Revolution, average Americans faced “rules against burning leaves in their own backyards.”

Suddenly you could break a federal rule without even leaving your house—and without meeting a regulator face-to-face.

“When Americans did meet a regulator,” Decker writes, “that person was now very likely to identify with a liberal social movement.”

Saving the Lakes, Streams, and Rivers at Any Cost

Protecting the environment was the mother of all causes—individual rights and the Constitution be damned.

“They paved paradise and put up a parking lot,” Joni Mitchell crooned in 1970. “Took all the trees and put ’em in a tree museum… Hey farmer, farmer, put away that DDT now. Give me spots on my apples, but leave me the birds and the bees…” The song was covered by vocal troupe The Neighborhood and became a top-40 hit that summer.

After a decade of affluence, economic growth, and progress, environmental activists wanted America to slow down, cut back, and atone. America’s land, air, and water needed to be protected from the American people.

Environmental anxiety even captured the White House. “The 1970s absolutely must be the years when America pays its debt to the past by reclaiming the purity of its air, its waters, and our living environment,” President Nixon said on New Year’s Day of 1970.

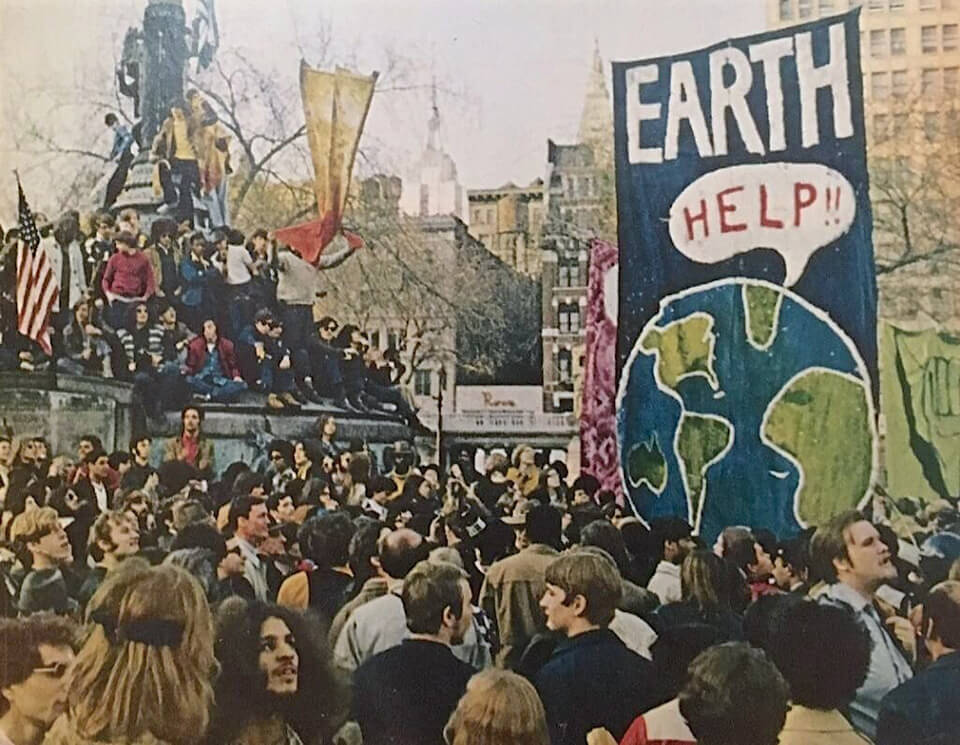

When the country celebrated the first Earth Day a few months later, so many congressmen and staffers joined rallies “that Congress was forced to close down,” a White House staffer later recalled. About 20 million Americans attended Earth Day demonstrations—an astonishing number. At Kent State University, students staged a funeral for “the children of tomorrow” to protest pollution. One journalist called Earth Day “the largest one-day outpouring of public support for any social cause in American history.”

In December of that year—riding this wave of environmentalist fervor and on the urging of his own Citizens Advisory Council—President Nixon created the Environmental Protection Agency.

Unlike older federal agencies, the EPA didn’t need to be convinced that its officers should engage in “positive detective work.” The agency had that mindset from the beginning—it undertook 1,000 enforcement actions against Americans in its first two years.

Nader and his proteges helped boost the EPA’s power. In the spring of 1971, David Zwick—a Nader recruit from Harvard Law School—released Water Wasteland, a 700-page study that announced there was “almost no significant body of clean water” left in America. It was a dramatic claim, but it makes sense, given that the study defined “water pollution in the strictest sense” as “man’s alteration of existing rivers, oceans, lakes, and streams.”

Merely by living everyday lives—building houses, farming, gardening, boating—people were guilty of water pollution.

Water Wasteland argued that the federal government needed to be far more aggressive in finding and punishing water polluters. At one point, in an eye-popping analogy, Zwick and his coauthors compared the government’s too-soft approach with American businesses to allowing a convict “who has been committing six murders, rapes, and armed robberies a week” to stay on the street.

Altering waterways, in other words, was akin to violence. Perpetrators needed to be punished.

The campaign for clean water was quickly becoming a war on human activity and freedom—and Zwick was a wartime consigliere. He proposed mobilizing every single employee in the federal government as a de facto spy network to sniff out water polluters: Congress, Zwick said, should make it a crime for federal employees to “knowingly fail to report pollution problems to EPA.” Federal employees who didn’t turn in polluters would face “fines and/or jail sentences” under Zwick’s proposal.

Some in Washington balked at Zwick’s ambitious schemes and dubious claims. One critic said Water Wasteland read “like an unedited collection of seminar papers in Poly Sci 300.”

But many in Congress loved the study and its charismatic young author. Members invited the 30-year-old Zwick to testify, along with Nader, on Capitol Hill about their findings. Soon Zwick and Nader were helping members draft a bill to dramatically overhaul federal water pollution efforts.

That bill would become the Clean Water Act in 1972. (The Clean Water Act passed despite a moment of clarity by President Nixon, who vetoed the law because it was too expensive. Congress overrode the veto.)

Zwick didn’t get everything he wanted, but he got plenty. The Clean Water Act allowed the EPA to fine or jail anyone who knowingly or unknowingly spilled dredged or fill material into “waters of the United States.” Ambiguities in the Act presumably became broad delegations—for example, exactly which waters were covered?—emboldening environmental agencies like the EPA to interpret its authority as far as legally possible and beyond. Thousands of streams, creeks, wetlands, and soggy residential lots crisscrossing the country were now in the EPA’s sights.

Thanks mainly to Zwick and Nader, the two-year-old EPA had become one of the most powerful agencies in Washington—and was now the ideal home for the new, incoming generation of activist federal employees.

By the end of the seventies, the EPA had hired so many new employees that it was four times the size of the Federal Trade Commission, Securities and Exchange Commission, Federal Power Commission, and Interstate Commerce Commission combined.

Source: New York Public Library

A New Hope

But the government wasn’t the only one attracting professionals to a cause.

In early 1973, a group of lawyers left Governor Ronald Reagan’s administration in California after a series of high-profile battles between the administration and progressive public interest groups. These lawyers—in particular, an aide named Ronald Zumbrun—saw the California policy fights as part of a larger, nationwide clash between two competing visions of government: a government that protected individual rights versus a government that furthered collectivist goals at any cost, including environmental goals.

This philosophical clash, they believed, would ultimately be won in the courts.

On March 5, 1973, the group of former Reagan attorneys incorporated as Pacific Legal Foundation, with Ronald Zumbrun as president. PLF had a starting budget of $117,000. Within the first year, PLF attorneys accepted ten cases for litigation.

“At least one public interest law firm is working on behalf of the public,” Reagan said of PLF.

It was a critical time for the country: Millions of Americans were being told what they could and couldn’t do with their private property. The federal government was populated with a new kind of bureaucrat, committed to furthering draconian environmentalist goals at the expense of individual rights and the Constitution’s separation of powers. The administrative state was ratcheting up in size, budget, and influence.

But PLF had begun pushing back. Case by case, PLF attorneys tested the constitutionality of sweeping federal laws and regulations that often sublimated individual rights and our Constitution’s structure in the aggressive pursuit of absolutist environmentalist causes—causes that largely ignored the environmental benefits of people putting their private property to beneficial use.

“There are at least 86 major federal programs to enhance and protect the environment,” an early PLF newsletter reported. “Each program is backed by hundreds of regulations and administrative requirements. The salaries for the people in the agencies which administer and enforce these laws come out of your pocket.”

By the end of the decade, there were over two million federal employees in the growing executive branch. But PLF was also growing: By 1980, the firm had offices on both coasts and donors in every state.

Today, the activist strain of government assembled in the 1970s is still very much alive—and still eagerly trying to use the hammer of regulatory power to push forward new agendas, sometimes through old statutes passed during that era.

But as PLF enters its 50th year, we have more attorneys working in more states across the country than at any other time in our history to relentlessly fight back against government overreach. Pacific Legal Foundation attorneys are, as Washington Post columnist George Will recently put it, “litigators with no shortage of things to litigate against.” ◆

Apocalyptic Environmentalists Want Fewer Humans on Earth

Joseph Kast

Creative Manager

Larry Salzman

Director of Litigation

Last July, two climate activists glued their hands to the 540-year-old Botticelli painting Primavera at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy. The painting, which depicts mythical figures in a green garden, is one of the most studied and praised in Western Civilization. It is thought to be an allegory about the abundance of nature.

A third activist then unrolled a banner that said, “Ultima Generazione No Gas No Carbone” (Last Generation No Gas No Coal). The activists call themselves Ultima Generazione. They believe that, without drastic government action, the world will soon be destroyed by climate change.

In the U.S. and Great Britain, the activist group Extinction Rebellion (or XR) uses similar tactics for the same reason. Front and center on its website is this dire text: “Life on Earth is in crisis. Our climate is changing faster than scientists predicted […] Social and ecological collapse. Mass extinction. We are running out of time, and our governments have failed to act.”

Extinction Rebellion frequently makes headlines for its “nonviolent” demonstrations, which mostly involve blocking traffic and public transport. Lest you assume this is strictly a college student movement, an 83-year-old XR activist glued his hand to the side of a subway car at one protest, saying he was doing it for his grandchildren, and that it upset him “to see God’s creation being wrecked across the world […] I’m longing for the government to take some actions…”

In another demonstration last year, climate activists blocked traffic to bring attention to their pet issue. A tearful woman begged them to move, as she was on her way to visit her sick mother at the hospital. After the incident, XR’s co-founder Roger Hallam was asked in an interview how he would’ve responded to the woman: “I’d have stayed there.” The interviewer then asked, “If it were an ambulance and there was someone in there that could potentially die, would you stay there?”

“Yep.”

Apocalyptic Environmentalism

Environmental groups like XR and Ultima Generazione share two qualities: First, a panicked certainty that climate change is going to end life on earth very soon, or at least make it much worse for most of us, and second, that only governmental restrictions on liberty and property can prevent it.

Granted, these activists are on the radical end of the spectrum among environmentalists. But over the past 50 years, there has been a shift of the entire spectrum toward what author and longtime environmentalist Michael Shellenberger calls “apocalyptic environmentalism.” While most people who describe themselves as environmentalists don’t consciously identify with apocalyptic environmentalism, key policies they support have their intellectual origins in this fringe.

Environmentalism didn’t always have this apocalyptic tone. In fact, the early American conservation movement’s purpose was to protect and use natural resources for human benefit and enjoyment. Our relationship to the environment was one of mutual benefit.

Apocalyptic environmentalism, on the other hand, sees humanity and the environment as fundamentally at odds. Adherents are never far from advocating population reduction alongside demands for more government action.

The activist group Extinction Rebellion dresses in red robes to protest an oil rig in Scotland.

By the late 2010s, distaste for humanity was so trendy in environmentalist circles that many began arguing it was unethical to bring more human beings into the world. The Cato Institute’s Chelsea Follett collected a sample of telling headlines:

Recent examples of writings that are warming to the idea of human extinction include The New Yorker’s ‘The Case for Not Being Born,’ NBC News’ ‘Science proves kids are bad for Earth. Morality suggests we stop having them,’ and The New York Times’ ‘Would Human Extinction Be a Tragedy?’ which muses that, ‘It may well be, then, that the extinction of humanity would make the world better off.’ Last month, the progressive magazine Fast Company released a disturbing video entitled, ‘Why Having Kids Is the Worst Thing You Can Do for the Planet.’

Follett also notes that apocalyptic environmentalism unsurprisingly celebrated what most people regarded as an awful and socially shattering pandemic in 2020: “The New York Times has noted that an upside of social-distancing efforts is that they may help fight climate change, and CNN ran the headline ‘There’s an unlikely beneficiary of coronavirus: The planet.’ The BBC’s environmental correspondent gleefully reported that air pollution and CO2 emissions fell rapidly as the virus spread.”

This attitude has become so deeply rooted within our own government that popular New York Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez once mused, “It is basically a scientific consensus that the lives of our children are going to be very difficult [due to climate change], and it does lead young people to have a legitimate question: is it OK to still have children?” In another livestream, she claimed that unless drastic government action is taken immediately, “the world is going to end in twelve years.”

Doomsday cults are nothing new. But over the past 50 to 60 years, apocalyptic environmentalism has gained an outsized influence in culture and public policy—in large part thanks to one American biologist.

Source: Rockefeller Archives

Paul Ehrlich, ‘Irrepressible Doomster’

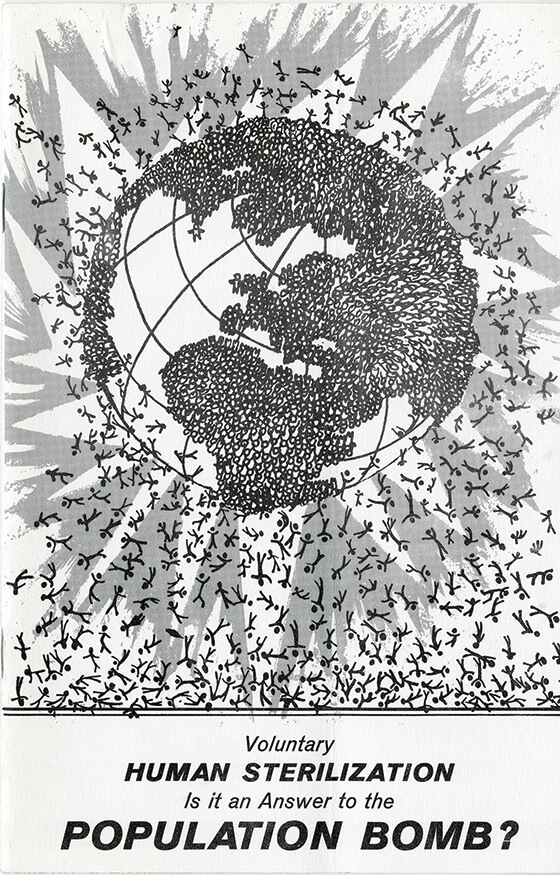

Stanford biologist Paul Ehrlich began his 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb with a bleak pronouncement: “The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.”

Ehrlich had written the book at the urging of Sierra Club’s then-executive director David Brower, who penned a foreword explaining man would soon be destroyed by his “own brutality”—that is, his reckless mistreatment of the natural environment. “We can no longer afford merely to treat the symptoms of the cancer of population growth,” Brower wrote. “[T]he cancer itself must be cut out.”

Ehrlich argued the planet was “dying.” Human activity was disrupting and destroying ecosystems. He called particular attention to America’s waterways, which, he said, were being polluted at such an alarming rate that by 1984, “the United States will be quite literally dying of thirst.”

As science journalist Ronald Bailey puts it, Ehrlich was an “irrepressible doomster.” Yet despite—or, perhaps, because of—its alarmist predictions, The Population Bomb sold two million copies and was taken seriously by governments across the globe. Developing countries in Asia, South America, and Africa adopted population controls and conducted mass sterilization campaigns. Ehrlich founded Zero Population Growth, an advocacy group that promoted Ehrlich’s views in Washington, DC.

Not all of Ehrlich’s proposals won support. For example, he wanted the United States to create a federal Department of Population and Environment “with the power to take whatever steps are necessary to establish a reasonable population size in the United States and to put an end to the steady deterioration of our environment.” Fortunately, the “DPE” never got off the ground.

But the creation of the EPA in 1970 and the passing of the Clean Water Act in 1972 helped further Ehrlich’s mission to limit the impact of human activity on nature.

Snapshot: Is Development Like This a Sign of Life or a Sign of the Apocalypse?

This is Priest Lake, Idaho, where Mike and Chantell Sackett own property. The neighborhood has dozens of other houses—including houses much closer to the lake. But the EPA blocked housing on the Sacketts’ lot. Officials seemed eager to prevent further development of the area. One EPA official spoke admiringly of a 1932 aerial photo of Priest Lake that showed no roads or houses, “only a primitive trail.”

Anti-Human, Anti-Development

With the popular view that human beings were poisoning the planet—and would cause the apocalypse if the government didn’t intervene—regulators took steps to limit man’s effect on the natural environment.

In his book The Other Rights Revolution, Jefferson Decker writes that

environmental regulators of the 1970s did not want to build new improvements so much as to keep some things as they were—a marshy area undrained, an open field fallow, a historic building preserved, a mountaintop unmined…All the government needed was to rezone a property for open space or designate it as “protected” from future change…

The EPA’s long, bizarre history of declaring private land “protected”—and therefore unsuitable for human habitation—suddenly makes sense when you view it as the logical, practical extension of apocalyptic environmentalism.

In the case of Mike and Chantell Sackett’s lot in Priest Lake, Idaho, one EPA ecologist admitted in his 2008 site report that he examined a 1932 aerial photo before visiting the Sackett site. In that photo from 76 years prior, the surrounding area showed very little human development—only “a primitive trail.”

In preventing the Sacketts from building on their property, the EPA seems to be trying to rewind progress so the area can look more like that 1932 photo—with fewer humans and houses.

For those with a doomsday outlook, signs of human life are a blight on nature. And if the government isn’t successful in preventing more human development around waterways like Priest Lake, environmentalists argue, the consequences will be “dire,” as advocacy group Earthjustice put it. Sierra Club makes the fantastically insupportable claim that the Sackett case jeopardizes “the drinking water supplies of one in three Americans.” One climate change blogger lamented that the Supreme Court might favor “polluters over the planet.”

The Ultimate Resource

The irony of apocalyptic environmentalism’s growing influence is that every major doomsday prediction has turned out to be wrong.

Shortly after publishing The Population Bomb, Paul Ehrlich made an off-hand comment that if he were a gambler, he’d bet “England will not exist in the year 2000.”

Economist Julian Simon was so irked that he publicly challenged Ehrlich to a bet: Ehrlich and his fellow researcher John Holdren could pick several raw materials that they thought would soon become scarce and more expensive. Simon was confident the materials would actually become cheaper over time—and he was right. Ten years later, Ehrlich was forced to send Simon a check.

Simon knew something Ehrlich didn’t: The ultimate resource isn’t the environment, but rather the ingenuity of the human mind. In the decades since The Population Bomb was released, the world population has more than doubled. There is far more human activity—and far more construction by rivers and lakes—than when Paul Ehrlich was writing.

And yet the world has not ended. We’re not dying of thirst. There hasn’t been mass starvation or the dawning of a new ice age.

Instead, the world has become much richer. Global poverty has declined by more than half since 1990. The percentage of people living in extreme poverty (less than $1.90 a day) has fallen to less than 10%, a world-historical low. Two years after Paul Ehrlich predicted mass starvation in The Population Bomb, Norman Borlaug won the Nobel Prize for developing a high-yield, disease-resistant wheat that would feed billions of people.

And the environment is thriving too: The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization notes that wildlife species in the U.S. “have increased dramatically since 1900.” The science journal Nature has found that deforestation trends have totally reversed in the past 40 years, with a 7% increase across the earth’s surface (the size of Texas and Alaska combined). In the United States, far more trees are planted each year than harvested, a trend encouraged in part by paper and lumber industries’ incentive to have a dependable, sustainable resource to sell. Technological advances in fertilizers, irrigation systems, and other farming methods have turned out to be a boon for both people and the land.

Still Predicting Doomsday

Apocalyptic predictions have continually been proven wrong, but the environmentalists who make them still influence public policy.

Ehrlich’s research colleague John Holdren didn’t allow the loss of the Ehrlich-Simon bet to hinder his career in apocalyptic environmentalism. He served as the director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy for all eight years of the Obama administration.

Ehrlich himself continues to claim that mass starvation and civilizational collapse due to overpopulation is a “near certainty.” In a 2018 interview with The Guardian, Ehrlich likened the expanding human population to a “cancer cell” that will lead to a “shattering collapse of civilization” within the next few decades.

Novelist Jonathan Franzen caused a similar stir in 2019 when he presented the impending apocalypse as a near-certainty in an essay in The New Yorker.

To delay the end of the world, Franzen wrote, “overwhelming numbers of human beings, including millions of government-hating Americans, need to accept high taxes and severe curtailment of their familiar life styles without revolting…. Every day, instead of thinking about breakfast, they have to think about death.”

No thanks. Positioning the stakes as life-or-apocalypse makes it easier to justify restricting people’s freedom—for example, denying a couple like the Sacketts the right to build a home—but it’s not tethered to reality. If the government wants to ensure a better future for the world, it should empower the Norman Borlaugs of the world to innovate instead of making it harder for people like the Sacketts to develop their own land. ◆

Inconvenient Fact-Checking

Apocalyptic Predictions That Didn’t Come True

1499

Astronomer Johannes Stoffler predicts a global flood is coming in 1524.

1910

Astronomer Camille Flammarion predicts Halley’s Comet will “snuff out all life on the planet” later in the year.

1968

Biologist Paul Ehrlich predicts the United States will “quite literally be dying of thirst” by 1984.

1969

Paul Ehrlich predicts “England will not exist in the year 2000.”

1970

LIFE Magazine says “urban dwellers will have to wear gas masks to survive air pollution” by 1980.

1970

Paul Ehrlich says American life expectancy will be lowered to 42 years by 1980.

1988

Climate scientist James Hansen predicts New York’s West Side Highway will be under water by 2009.

1989

A United Nations environmental official predicts rising sea levels will wipe nations off the face of the Earth by 2000.

2004

Scientists Peter Schwartz and Doug Randall say Europe’s climate will become “more like Siberia’s” by 2020.

Meet Clean Water Act Criminals

Brittany Hunter

Editorial Writer

Paige Gillard

Attorney

When environmentalists celebrate the 50-year impact of the Clean Water Act, they talk about what the law means for animals and plant life. The CWA, they say, has helped fish, birds, and turtles thrive in America’s waterways.

“All this magnificent life”—meaning, non-human life—“is now in jeopardy” because of Pacific Legal Foundation’s Sackett v. EPA case, The New Republic complained.

First, that’s simply not true: Sackett v. EPA is not about the quality of America’s waterways. It’s about the government preventing housing on land that is otherwise buildable. It’s about executive overreach. If the Sacketts are allowed to build a home in their Idaho subdivision, it won’t affect the salmon of Seattle or shorebirds of Long Island. (It won’t even affect Priest Lake, which is 300 feet away, because there’s no water flowing from the Sacketts’ property to the lake!)

Second, there’s another kind of “magnificent life” that’s been impacted by the Clean Water Act over the past 50 years: human life.

As one former EPA official told us in an interview, Section 404 of the Clean Water Act—which requires a permit if you’re filling “navigable waters” with dirt or sand and is at the heart of the Sackett case—isn’t targeting industrial polluters. Unlike other sections of the Clean Water Act, Section 404 primarily targets individuals.

“And it was okay when you were regulating DuPont or General Motors,” the former official, who left the EPA 20 years ago, said. “But when you regulate the thousand-acre farm or the 5,000-acre farm, or the individual homebuilder who’s building a couple houses on a lot—I mean, that’s when it gets very politically controversial.”

Despite rising concerns on the left about overcriminalization, unjust financial penalties, incarceration, and civil asset forfeiture, progressive groups don’t seem to care that farmers and homeowners have been harassed, fined, threatened, robbed of their property rights, and even jailed by the government under the Clean Water Act.

But anyone who talks about the impact of the Clean Water Act should know these human stories.

Father and Son Jailed in Florida

In 1986, father and son team Ocie and Carey Mills were preparing a quarter-acre lot near Pensacola to build a fishing cabin. While spreading clean sand, they were visited by an official from the Army Corps of Engineers (which has overlapping jurisdiction with the EPA) who told them they were filling a wetland and had to stop.

The Millses consulted with a state agency, which gave them the okay to keep working. But the Corps had them arrested and indicted for violating the Clean Water Act.

The father and son spent 18 months in federal prison.

After the Millses were released, they were ordered to restore the wetlands. They tried, but the Corps hauled them back into court, saying they hadn’t removed enough sand. This time, Ocie and Carey convinced a new federal judge to visit the property.

Incredibly, once the judge visited the property, he said he didn’t think the property was actually a wetland to begin with! In a 1993 opinion, the judge wrote,

This case presents the disturbing implications of the expansive jurisdiction which has been assumed by the United States Army Corps of Engineers under the Clean Water Act. In a reversal of terms that is worthy of Alice in Wonderland, the regulatory hydra which emerged from the Clean Water Act mandates in this case that a landowner who places clean fill dirt on a plot of subdivided dry land may be imprisoned for the statutory felony offense of “discharging pollutants into the navigable waters of the United States.”

At this point, PLF joined the fray and tried unsuccessfully to have the Millses’ convictions reversed by the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals. The court said it was too late.

Several years later, Pacific Legal Foundation vice president Jim Burling ran into the prosecutor from Ocie and Carey’s case at an environmental law conference. Jim, who’s never one to mince words, remembers their encounter:

I asked him, “With all due respect, after what you did to Ocie and Carey Mills, how can you sleep at night?” He laughed, and said, “My wife asks me the same thing.” And then he continued to explain how Ocie and Carey’s belief in their property rights was just too old-fashioned, and they needed to adjust their thinking to modern times.

Maine Retiree Locked in Eight-Year Legal Battle

Gaston Roberge had his fair share of trials and tribulations long before his legal battle against the government even began.

After surviving three heart attacks, chemotherapy, and losing sight in one of his eyes, the New England businessman decided it was time to retire. In 1986, with medical bills still piling up, he and his wife Monique planned to sell their empty 2.8-acre lot in Old Orchard Beach, Maine, near where they once ran a motel. The proceeds from the sale would help fund Gaston’s medical bills and retirement.

The couple’s plans would have to wait, however, as they would spend the next eight years (and thousands of dollars in legal fees) fighting the government.

For years, Gaston had an arrangement with the town where they paid him to dump clean fill—rock, brick, ceramics, concrete, and asphalt paving fragments—on his land. Gaston never imagined this agreement would set off any red flags with the federal government. But right after a developer offered Gaston $440,000 for the property, the Army Corps of Engineers came out of the woodwork claiming that his plot of land was a wetland protected by Section 404 of the Clean Water Act. Gaston had no idea his land was considered a wetland. The government didn’t care. Army Corps officials asserted that because he had allowed the town to deposit clean fill on the land, he was guilty of illegally filling a wetland without a permit—an offense often accompanied by astronomically high fines.

Gaston wasn’t a polluter. He wasn’t big industry. The fill dumped on his land wasn’t even his. Why was the government ruthlessly going after an aging ex-motel owner in Maine?

To say Gaston and Monique were shocked would be an understatement. Suddenly they’d found themselves accused of violating a federal environmental law that was completely unknown to them. Worse, the buyer who’d offered them $440,000 withdrew the offer, frightened away. Instead of a nest egg, the Roberges were stuck with an empty lot they couldn’t sell.

For the next eight years, Gaston battled the Army Corps in court. The government had effectively taken his property and left him with nothing, violating the Fifth Amendment (which says the government cannot take private property without just compensation). And for what? Gaston wasn’t a polluter. He wasn’t big industry. The fill dumped on his land wasn’t even his. Why was the government ruthlessly going after an aging ex-motel owner in Maine?

The chilling answer appeared when a government memo came to light in the discovery phase of the case: An Army Corps official wrote, “Roberge would be a good one to squash and set an example—Old Orchard is heating up these days.”

In other words, the government’s actions weren’t about Gaston Roberge at all. In fact, the Corps was eventually forced to acknowledge that Gaston’s lot didn’t even contain wetlands.

The government’s primary motive was to hit back against property development on the Maine coast, and it didn’t care that it was running roughshod over an innocent man to do it. In 1994, the government finally settled with Gaston, who was then 81 years old, for $338,000.

Meanwhile, the Corps official who’d suggested making an example out of Gaston kept his position of power—although his supervisors did require him to attend a sensitivity course.

Veteran in Montana Loses 18 Months

Joe Robertson was an elderly veteran of the U.S. Navy. He and his wife, Carri, lived deep in the Montana woods right at the edge of a dense forest. A breathtakingly beautiful backdrop to build a home, it was also prone to devastating wildfires that threatened property and lives.

The Robertsons ran a firefighting truck support business and knew how essential it was to have a nearby water supply if they wanted to protect your home and surrounding forest area from fire. But because they were deep in the forest, the Robertsons didn’t have a robust water supply: The nearest source was a foot-wide, foot-deep nameless channel that flowed through a clearing close to their home. It wouldn’t be enough to fill firetrucks in the event of a fire close to the Robertsons’ home—so Joe dug some small water supply ponds around the channel that could fill several trucks.

Now: Unlike Gaston Roberge or Mike and Chantell Sackett, Joe Robertson didn’t live near an ocean, lake, or river. He was deep in the Montana forest. The small channel Joe dug around was more than 40 miles away from the closest river.

But the government showed up. The EPA claimed the small channel was a federally protected “navigable water” and that Joe had violated the law when he dug the ponds without first getting a permit. Officials also claimed that some of the ponds crossed over onto government land.

Joe didn’t get off easy: In 2017 the government slapped him with criminal charges. He was found guilty, fined $130,000, and sentenced to serve 18 months in prison. He was 77 years old at the time.

Pacific Legal Foundation asked the Supreme Court to review Joe’s conviction. Before the Court could respond, however, Joe passed away. He was still technically on parole when he died and had spent most of his last two years in prison.

One month later the Supreme Court responded by immediately remanding the case to the Ninth Circuit. Joe’s widow, Carri, became PLF’s client in the case.

The Ninth Circuit vacated Joe’s conviction and $130,000 fine. The court even ordered the government to pay back Carri the amount Joe had already paid in restitution.

It was a legal victory—but one that was bittersweet for Carri, who’d lost precious time with her husband during his final years.

Surely, sending an elderly man to prison for protecting his land was not a good use of government resources. In his own way, Joe was being a responsible steward of the environment: He was trying to ensure wildfire didn’t destroy acres of remote Montana forest.

But instead of working with him, the government punished him.

Welder Threatened in Wyoming

Andy Johnson is a welder with the United Steelworkers Union. He and his wife wanted to raise livestock—steer and horses—on the nine acres where they live with their four daughters in Fort Bridger, Wyoming. To provide the livestock with water, Andy decided to build a stock pond: a small manmade pond for watering animals.

His local State Engineers Department approved of the plan: “They came out to our property and examined and surveyed the land,” Andy remembers. “They were excited about the project and said our property was a perfect place for a pond.” The engineers also told Andy that there were “literally thousands” of stock ponds throughout Wyoming.

After getting the proper permit, Andy and his wife spent a year saving up enough money for the project, then another six months constructing the pond.

“We had invested a lot of time and money into the pond,” Andy says. “Our main goal was to provide a safe place for our livestock to drink and a place for our kids to play.”

Then Andy got a phone call.

A neighbor had informed the federal government about the project. Even though Andy had a permit, and even though the Clean Water Act expressly exempts stock ponds from Section 404, the Army Corps of Engineers said they needed to inspect the property. Then the EPA came and did a second inspection. When the EPA official spoke to Andy, he said he wasn’t sure yet if the stock pond was in violation, “but we would have to spend a lot of money and prove that we were not,” Andy remembers. “Everything about that man and the EPA felt wrong.”

Soon Andy received an EPA compliance order demanding that he hire a consultant and put together a plan to rip out the pond and restore the property. If Andy didn’t comply, he’d face possible criminal charges and civil fines of $37,500 per day.

“We were shocked and devastated,” Andy says.

With Pacific Legal Foundation’s help, Andy sued—and the EPA eventually settled, agreeing to drop the fines and charges as long as Andy planted willows around the pond.

If the EPA treated property owners like Andy as partners instead of criminals—if officials had asked Andy to plant willows from the beginning instead of threatening him—Andy’s family would have been saved two years of anxiety and litigation, and the EPA could have focused its taxpayer-funded budget on actual polluters.

Andy Johnson at his stock pond.

A Better Way

The environment is worth protecting. That’s why it’s such a shame the EPA has chosen to villainize individual property owners who are perfectly situated to partner with the agency and take on the responsibility of private conservation.

Contrary to what activists and the government may believe, voluntary environmentalism is not just a pipedream.

For example: After the beaver population in Oregon waned, endangering plant life that relied on beaver dams for sufficient water, a small group of ranchers banded together to protect the land by creating artificial dams. Not only did land conditions improve, but native fish and bird populations were also restored.

Unfortunately, the government ended up penalizing this group of ranchers, forcing them to pay fines and get permits for work they’d already done—essentially punishing them for their voluntary conservation.

This villainization of private property owners isn’t rational. In fact, according to researchers with the Center for Conservation Innovation (a project of Defenders of Wildlife), 80% of the country’s most richly biodiverse habitats are on private property—despite the fact that, if you add up federal and state landownership, the government owns over a third of the country’s land.

If governments at all levels worked with individual landowners like Joe Robertson, Andy Johnson, and the small group of Oregon ranchers, just imagine what could be accomplished.

Instead, the government is disincentivizing private responsibility and turning would-be partners into criminals. ◆

What People are Saying About Sackett v. EPA

“…potential landmark administrative law case challenging a giant regulatory land grab…”

![]()

“…case of ‘dream house’ stopped by EPA…”

“…most important water-related U.S. Supreme Court case to come along in a generation…”

“…a high-stakes case that could narrow the government’s power…”

![]()

“The court’s ruling in Sackett could offer the final word on this issue…”

“…potential for a breakthrough for property owners all over America…”

“…will potentially shape EPA’s rulemaking…”

“…majority of the Supreme Court seemed skeptical of the Biden administration’s defense…”

![]()

“…a worrisome case…”

![]()

Showdown at the Supreme Court

Damian Schiff

Senior Attorney

Monday, October 3, 2022: The first spectator arrived at midnight. He brought a sleeping bag and an umbrella, then waited outside the Supreme Court all night while it drizzled on and offOther spectators arrived between 2 and 6 a.m. By the time I arrived at the Supreme Court around 9:00 a.m., there was a line of people down the block, waiting in the cold.

It was the first time since the outbreak of COVID-19 that the public was allowed into the courtroom for oral arguments. Everyone in line was hoping to get a seat for Sackett v. EPA, the opening case of the new term—and new Justice Ketanji Jackson’s first appearance.

In front of the Court steps, a handful of environmentalist protestors took turns speaking from a podium. “Water knows no boundaries,” one speaker said, looking into a camera. “It’s like the very blood that runs through our veins.”

Another protestor started a chant: ‘When I say ‘clean,’ you say ‘water’! Clean! Water!”

Leading Up to Oral Arguments

The Supreme Court hears roughly 70 cases each term, selected from 7,000 to 8,000 petitions submitted by attorneys across the country. This term, two of the cases on the Court’s docket are Pacific Legal Foundation cases:

But first, Sackett v. EPA, a case I’ve been working on since 2008.

I’ve argued at the Supreme Court only one other time and it was in this same case, ten years ago. We won unanimously then; but at that point we were simply arguing for the right to bring a challenge in the first place. In his 2012 Sackett I opinion, the late Justice Antonin Scalia (correctly) pointed out the Clean Water Act wasn’t designed for “the strong-arming of regulated parties into ‘voluntary compliance’ without the opportunity for judicial review.”

It’s like being in a play. There are huge velvet curtains hanging behind the bench, and right at 10:00 a.m. a bell rings and the curtain pulls back.

Sackett II would be more difficult. We’re trying to get the Court to clarify which wetlands are protected by the Clean Water Act: only wetlands with a surface connection to traditional navigable waters, as Justice Scalia held in his 2006 plurality opinion in Rapanos, or also even “soggy residential lot[s],” as the Ninth Circuit dubbed the Sacketts’ property.

A week before oral argument, I flew from my home in California to Washington, DC, for an intense week of final prep, including three moot courts where legal experts—most of them former Supreme Court clerks—took on the role of Justices and peppered me with questions.

I felt ready. But I still had trouble sleeping the night before.

At the Court on Monday morning, before arguments began, I spoke to an attorney in the case immediately following ours. He’s a former U.S. solicitor general at the Department of Justice and has argued dozens of cases at the Supreme Court. He told me he still gets nervous every time.

Nothing—no federal appellate court—is like the experience of arguing at the Supreme Court. The lectern where you stand is only three or four feet from the bench where the Justices sit. The bench curves around you and the Justices are spaced out so that you can’t look at all nine at once. They’re almost surrounding you.

It’s like being in a play. There are huge velvet curtains hanging behind the bench, and right at 10:00 a.m. a bell rings and the curtain pulls back. The Justices process in. As an attorney, your opening statement is almost like a soliloquy.

Except a soliloquy isn’t interrupted by questions.

A Supreme Court Argument Years in the Making

When the Sacketts started building their home in 2007, George W. Bush was still president, the first iPhone hadn’t launched yet, and there were a billion fewer people on the planet.

It’s been a long road to Sackett II oral arguments.

Is the Sacketts’ Land ‘Adjacent’ to the Lake?

Oral arguments are scheduled to last an hour, with each side given 30 minutes.

Instead, it lasted almost two hours. That’s because of how many questions the Justices asked.

It quickly became clear that the Justices weren’t satisfied with the murky “significant nexus” test that the EPA currently relies on to claim jurisdiction over land like the Sacketts’.

“I… understand some of your points about the significant nexus test,” Justice Elena Kagan told me. “Is there anything in the middle?”

She and several others, including Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Comey Barrett, seemed eager to develop a new test for the EPA’s authority over wetlands—a test based on whether a wetland is “adjacent” to a traditional navigable water.

There is a 1977 amendment to the Clean Water Act that briefly mentions “wetlands adjacent” to navigable waters. The EPA has largely focused its own arguments elsewhere, but several Justices asked me about this phrase. Justice Kagan suggested the line “means more than you think.”

One problem, of course, is that no one in the room seemed to agree on exactly what “adjacent” means. We debated the definition for so long that at one point Justice Clarence Thomas said, “I don’t want to use the term ‘adjacent.’ I’m done with that word.”

I maintained that when talking about geographic features, adjacent means touching. If someone says they have two adjacent parcels of land, that clearly means the lots are touching.

But Justice Sonia Sotomayor argued Congress would have used the word “abutting” if that’s what they meant. She said the Clean Water Act includes the word “abutting” elsewhere in the statute, and when I respectfully disagreed, she said, “Oh, it actually does. Assume it does.” Meanwhile, unbeknownst to everyone in the courtroom (who surrender their phones upon entry), law professor Jonathan Adler was fact-checking Justice Sotomayor on Twitter: Abutting does not, in fact, appear in the statute.

Bear in mind: The Sacketts’ property is 300 feet from Priest Lake. Technically the EPA isn’t arguing the property is adjacent to the lake, but rather that it’s adjacent to a ditch 30 feet away, which runs into a creek a few thousand feet west of the site, which later drains into the lake. Justice Neil Gorsuch called that theory of adjacency “kind of a daisy wheel spun out from the lake” and “rather complicated when one looks at the map.”

At one point, the EPA’s counsel suggested that you could argue the Sacketts’ lot is adjacent to the lake 300 feet away. “They” (meaning, the EPA) “do not think 300 feet is unreasonable for adjacency,” the counsel said.

Justice Gorsuch pounced on that. “So how about 3,000 feet?” he asked. “Could be?”

“I don’t—I don’t know the answer to that, Justice Gorsuch,” the counsel replied.

Justice Gorsuch pressed. “Could it be three miles?”

They went back and forth like that a few times, with the EPA’s counsel unwilling to put a definite number on how far a property can be from a waterway and still be considered adjacent.

Then Justice Gorsuch hit an excellent point: “If the federal government doesn’t know, how is a person subject to criminal time in federal prison supposed to know?”

PLF attorneys at the Supreme Court the day of Sackett oral arguments. From left to right: Jeff McCoy, Joshua Thompson, Damien Schiff, Charles Yates, Paige Gilliard, and former PLF attorney Tony Francois.

Definition of Waters

In another interesting exchange, Justice Samuel Alito asked the EPA’s counsel, “What is your understanding of the term ‘waters’?”

This was the government’s response:

We think it—so our understanding of it is reflected in the agency’s regulations, which have for 45 years spelled out the different sorts of waters that are covered. I think, if I were to try—going to reduce it to a phrase, it would be geographic features that are characterized by the presence of waters.

That definition could potentially include huge swaths of private property, as Justices Barrett and Thomas noted. Justice Thomas asked about where he grew up in the low country of Georgia, where most of the land is marshy. Justice Barrett asked about where she grew up in New Orleans, where “the whole thing is below sea level.”

“We have no basements because, if you dig far enough in anybody’s yard, you hit water,” Justice Barrett said. Then she asked: Does that mean that anyone who builds a backyard pool in New Orleans needs to get a Clean Water Act permit?

In other words: There needs to be a limiting principle. The Justices had a hard time getting the EPA’s counsel to draw a bright line. “The agencies have told me they do not draw bright-line rules,” the counsel said at one point.

Water Goes Everywhere Eventually

Ultimately, this case is a battle of different versions of textualism: our idea of textualism versus a different kind of textualism that has become prevalent on the left—a textualism informed by purpose.

Just because the EPA has been misinterpreting its authority for decades doesn’t mean the Court should endorse its misinterpretation.

Several textualist Justices on the Court, including Justice Kavanaugh, seemed to be searching for something in the text of the Clean Water Act on which to form a “third test” that’s more environmentally sensitive than Justice Scalia’s test in Rapanos—which is why they seized on the word adjacent in the 1977 amendment.

Justice Kavanaugh asked me a surprising question: He asked why the Court shouldn’t stick with how “every administration since 1977” has interpreted the CWA.

I gave a textualist answer: I spoke about the ordinary meaning of the words in the statute. But here is, perhaps, a better answer: Justice Scalia wrote eloquently about the “damage done to our separation-of-powers jurisprudence” when the Supreme Court embraces “the adverse-possession theory of executive power.”

In other words, just because the EPA has been misinterpreting its authority for decades doesn’t mean the Court should endorse its misinterpretation.

The Clean Water Act is a law that can sweep very broadly. It’s hard to know whether you’re regulated, and if you guess wrong—for doing otherwise-normal activity, like building a house—it can be catastrophic. And there aren’t very many statutes out there that have that potent brew of huge penalties, lack of notice, and the potential to regulate very normal, everyday conduct. That makes it scary.

There’s a good reason PLF has been involved in the Sackett case since 2008: If the EPA can swoop in and block housing on a residential lot 300 feet from a lake, how many millions of acres around the country will fall under their control? Will the EPA stop construction in rural Georgia next? In New Orleans?

Without clear Court guidance on the Clean Water Act, the federal government’s authority over private property is virtually limitless. As Chief Justice John Roberts said at one point during oral arguments, “Water goes everywhere eventually.”

The Supreme Court will likely give us its decision in the spring. ◆

Make your year-end gift today!

The hand of government has rarely felt heavier than over the past few years.

It’s high time to get the bullying bureaucrats like those at the EPA under control.

Your year-end support will empower more citizens to fight back against overreaching government—and win!

Make your gift by December 31.

Mail your check made out to “Pacific Legal Foundation, 555 Capitol Mall, Suite 1290, Sacramento, CA 95814”

Donate online at pacificlegal.org/year-end

Make a gift of stock: pacificlegal.org/stock